Nguyen Khac Su, Institute of Archaeology,

Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences.

Abstract: For nearly a decade (2010-2019), the Institute of Archaeology of the Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences has been conducting a cooperation programme with the Novosibirsk Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and has obtained many achievements. One of the most remarkable achievements of the cooperation programme was the finding of the excavations in Con Moong cave (Thanh Hoa province) and the Palaeolithic sites in An Khe (Gia Lai province). A geological stratum over 10.14m thick, which has remained intact in Con Moong cave, consists of many successive cultural layers and reflects changes in the palaeo- environment and cultural evolution of the prehistoric inhabitants in northern Vietnam from 70,000 BC to 9,000 BC.

Keywords: An Khe, Con Moong, Palaeolithic, Neolithic, archaeology, prehistory.

Subject classification: Archaeology

1. Introduction

Many academically confident and life-related achievements have been accumulated by the former Union of Socialist Soviet Republics (USSR) as well as present-day Russia in the sphere of archaeological research on the history of humanity. At the same time, the research programmes conducted in cooperation between Vietnamese and Russian archaeologists have provided specific findings and played a significant role in increasing awareness for history and improving research capacity.

In the early 1960s, Russian archaeologists came to Vietnam, taking part in providing archaeological training for Vietnamese researchers. We highly appreciate the contribution made by Professor P.I. Boriskovsky, who spent many years enhancing the capacity of the first Vietnamese archaeological researchers in Vietnam and participating in excavations for the research on primitive Vietnam. He received the Labour Medal, a noble reward, granted by the government of Vietnam.

For many years, including those of the resistance war against the Americans, various generations of Vietnamese archaeological researchers took training and graduated from universities in Moscow, Saint Petersburg (known previously as Leningrad), and other cities of the former USSR. On the anniversary of the October Revolution and the USSR Foundation Day, Vietnamese archaeological researchers often hold a scientific conference to discuss the Soviet archaeological achievements and the Russian - Vietnamese archaeological research cooperation [5], [6], [3], [2], [1]. Recently, the work titled “History of Vietnam” (Vietnamese: Lịch sử Việt Nam), consisting of six volumes, was edited and published by Russian historians to celebrate the 40th Anniversary of National Reunification of Vietnam in 2014. The first volume provides a summary of the archaeological materials on the period from the Stone Age to the Iron Age.

The cooperation in archaeological research and excavations is always seen as an important part in the cooperation between the two countries. In the past, many excavations were carried out on the site of Oc Eo culture by the Southern Institute of Social Sciences in cooperation with the Saint Petersburg Institute of History of Material Culture. In addition, the Institute of Archaeology (Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences) has also been conducting a cooperation programme with the Novosibirsk Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology (Russian Academy of Sciences) from 2009 to 2019. One of the most remarkable achievements of the cooperation programme was the finding of the excavations in Con Moong cave (Thanh Hoa province) and the Palaeolithic site in An Khe (Gia Lai province).

2. Excavation in Con Moong cave

The findings of the cooperative excavations in Con Moong cave (2010-2014) and its surrounding caves such as Hang Lai, Mang Chieng, and Hang Diem contributed towards the clarification of the primitive history of Vietnam in the transitions from the Pleistocene to the Holocene, from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, and from the primitive age to the civilised age, based on a geological stratum over 10.14m thick that has remained intact to show the cultural evolution from 72,000 BC to 7,000 BC.

Inside ten geological layers in Con Moong cave, some tools made of quartzite were found at a depth of 8.6m dating back to 72,000 BC. They are crude flakes of a small size. Those artefacts mainly include pointed hand axes, scrapers, razors, and carving knives. This cultural layer reveals a technique of lithic reduction that is completely different from those discovered so far in other caves in Vietnam. According to the palaeo-magnetic analysis, the archaeological materials show that the ave dwellers did not spend much time staying inside the cave since very few tools have been found, which is typical for colder climates.

The fifth, the sixth, and the seventh cultural layers are found at a depth ranging from 5.1m to 6.8m. The age of those layers is dated to 48,000 BC (layer 7), 44,000 BC (layer 6), and 35,000 BC (layer 5), based on the optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), a method for measuring doses from ionising radiation. A number of artefacts were found in those layers, including flake tools, small pebble choppers, quartzite and andesite, and limestone materials as well as semi-fossilised animal remains. However, the mollusc brought to the cave and used by man was only found in the fifth layer. Traces of rain were found in the upper fifth and lower fourth layers. The lithic reduction in those layers is different from that of the flake tools found in Nguom (Thai Nguyen province), Bailian cave (Guangxi, China), and Lang Rongrien (Thailand), where small flake tools show traces of the second modification.

Compared with the dwellers in the earlier layers, those in the fifth, the sixth, and the seventh lived more permanently inside the cave, but the traces remain very vague. A drastic change in climate took place during this period. A sudden phase of cold climate appeared, making limestone in the fifth layer shrink and break into small pieces, which is called limestone breccia by archaeologists. In such a climate condition, the dwellers made flake tools used for hunting small animals. This reflects the adaptation to the surrounding environment.

The third and fourth layers are located at a depth ranging from 3.6m to 5.1m. The absolute age of the fourth layer is dated to 34,000 BC, while that of the third one is dated to 26,000 BC or 25,000 BC. The dwellers of those layers made small pebble tools and flake tools from diabase, basalt, quartzite, and limestone. They hunted various species of animals and terrestrial molluscs, which were mainly mountainous snails. After the Last Glacial Period (20,000 years later), the climate became gradually warmer, so the dwellers stayed inside Con Moong cave more frequently. They step by step moved their shelter towards the cave entrance in the west. As they spent more time living in the cave, the snail shells were more fragmented and squeezed firmly into the cave floor due to their steps. As some geological change occurred, making rocks fall from the cave ceiling down to the cave floor, the cultural layer was greatly impacted, sliding down the cave shaft. The traces of the initial sedimentary block can be found in a long line running along the cave wall at present.

The second layer located at a depth ranging from 2.5m to 3.6m dates to 10 different periods from 17,000 BP to 13,000 BP, according to the radiocarbon dating (also known as radiocarbon-14 dating). The artefacts found in this cultural layer mainly include trimmed pebble tools of the Son Vi culture and bone tools. During those periods, inhabitants lived on hunting big mammals and collecting snails in mountains and streams. The dead were buried in a foetal position with stone tools. As shown by the palaeo-magnetic and pollen analysis, it was a clear tropical monsoon climate. The inhabitants collected molluscs to eat and made hundreds of pebble and bone tools, representing a transition of tool-making technique from Son Vi to Hoa Binh culture.

The latest habitation is found in the cultural layer at a depth of 2.5m, of which the age ranges from 13,000 BP to 7,000 BP. At that time, the cave dwellers also made and used trimmed pebble tools. In the early phase of the period, they made their stone hand axes sharpened at the blade. In the later phase, however, there were stone hand axes, of which all the faces were sharpened, and potteries as well. The dwellers experienced a palaeo-climate change with a wide range of hot, cold, and mild climate cycles mixed. There was a transition from the slightly dry and cold climate to the hot, humid, and monsoon one. During the period from 11,400 BP to 8,800 BP, the precipitation was very high. Like many other caves, consequently, the average sum of sediment carried into the cave amounted to 1cm per every 100 years. It is ten times higher than that of the previous period (from 20,500 to 11,400 BP) when the corresponding figure was just 0.1cm per every 100 years. In other words, the rainfall in the period from 11,400 BP to 8,800 BP increased the same, compared with the previous period. Due to the heavy and long rains, inhabitants in northern Vietnam spent more time living inside the caves during that period. Only after 7,000 BP, when the period of heavy rainfall ended, did people start to leave the caves for plains lying in the foothills, such as Da But (Thanh Hoa and Ninh Binh provinces), or ancient coastal areas, such as Quynh Van (Nghe An and Ha Tinh provinces). They even moved straight to islands to live and set up a prehistoric sea culture, like the owners of Cai Beo culture (Quang Ninh province and Hai Phong city).

The findings of the excavations in Con Moong cave provide a standard geological stratum that demonstrates the entire prehistoric cultural process and the adaptation of humans to the environment. The transition of the community structure from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic is also shown clearly by the excavations in Con Moong and its surrounding caves, such as Hang Lai, Mang Chieng, Hang Dang, Moc Long, Diem, and Nguoi Xua, which are closely attached to the karst topography and the biodiversity of Cuc Phuong National Park. Those historical materials are extremely significant for the compilation of the primitive history of Vietnam from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, when inhabitants changed their livelihood from hunting, gathering and foraging to the beginning of agricultural farming. Owing to the research findings, Con Moong cave and its adjacent sites have been ranked special national vestiges by the government.

3. Palaeolithic excavations in An Khe

One of the especially meaningful achievements in the archaeological research cooperation between Russian and Vietnamese researchers was obtained in the research and excavations of the Palaeolithic sites in An Khe (Gia Lai province). The existence of the early Palaeolithic technique was confirmed by the researchers through artefacts including hand axes, trihedral points, and choppers, of which the absolute age is determined to range from 806,000 ± 22,000 and 782,000 ± 20,000 BP, according to the Potassium-argon dating (K-Ar dating). It is the oldest cultural vestige among all the Palaeolithic vestiges discovered so far in Vietnam, marking the beginning of the history of Vietnam.

Since 2014, Russian and Vietnamese archaeologists have found 21 Palaeolithic sites in An Khe commune, of which four have been excavated, including Go Da, Roc Tung 1, Roc Tung 4, and Roc Tung 7. The geological strata in those vestiges remain intact, providing thousands of stone artefacts and hundreds of meteorite samples [10]. This is an important source of historical materials to determine the existence of the early Palaeolithic technique and its role in the cultural heritage of humanity.

Tools of the An Khe Palaeolithic technique were found in the vestige sites on some hills in An Khe Town. Those hills have an average height of 420 to 450m and are located along the Ba River. In reality, An Khe is one of 21 geographical sub- regions in Central Highlands. Named An Khe depression, it is a transitional area between Pleiku highlands in the west and the South Central coastal plain in the east.

The traces of the An Khe cultural technique are kept in a cultural layer, of which the thickness ranges from 25 to 40cm. The layer mainly consists of lateritised clay, which originally came from the granite weathering. There are also meteorite pieces, which fell from other planets to the dwelling places of ancient people. As initially recognised, architectural traces of the floors, on which ancient inhabitants lived, have been found on the sites. In some places, there are mainly tool- making traces, like the relics of a workshop. In some others, there are both living and tool-making traces.

Tools of the An Khe Palaeolithic technique were made of pebbles collected from the local river and streams. The pebbles have a large size and smooth grains. They mainly came from hard stone such as quartzite, denatured quartzite, and silica stone. On the tools, there are crude flake scars made by humans. Very few of them show traces of secondary modification. The toolkit of the An Khe technique consists of bifaces, unifaces, points, trihedral points, choppers, blades, scrapers, hammerstones, pestles, stone nuclei (cores), and flakes. Meanwhile, hand axes, trihedral points, unifaces, and crude chopping tools are the most typical for the artefacts found on the sites.

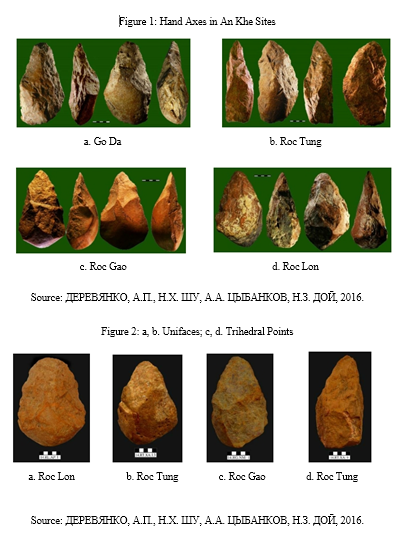

Hand axes are particular in the category of bifaces [4], which have been found in almost all the An Khe Palaeolithic sites, despite in a small quantity. The most typical for An Khe Palaeolithic hand axes are the four axes found in Roc Lon, Roc Gao, Roc Huong, and Roc Tung (Figure 1). They are made of quartzite pebbles of a large size.

Particularly, some of them have the shape of a javelin dart, of which one end was trimmed into a sharp point, and the other end was a round handle. The flake scars are mainly found in two third of the body from the pointed end. They were trimmed in both opposite sides, tapering from the outer edge to the centre, resulting in a flange running from the pointed end to the round handle. It is the thickest in the central part and gradually thinner towards the two edges.

The flake scars are small and overlap one another, resulting in a zigzag edge. The average size of the hand axes, the length, width, thickness, and the weight are 20.7cm, 11.9cm, 7.4cm, and 1.9kg respectively.

The unifaces account for a relatively large proportion of the artefacts, especially at some sites, such as Roc Lon, Roc Tung, and Roc Huong. They were made from large-sized oval pebbles, of which one side was almost completely trimmed off, and the opposite side was kept original. The flake scars concentrate on the two edges, creating a convex end and a handle. The average length, width, thickness, and weight are 20.7cm, 13.6cm, 8.4cm, and 2.3kg respectively (Figure 2 a, b).

Illustrative pictures

Regarding the trihedral points, they were made from pebbles, of which three faces on one end were trimmed into a point, and the other end was left original as a handle. When a pebble had originally two flat faces forming an obtuse angle, they just needed to trim one more face. When a pebble had originally one flat face, they needed to trim two more flat faces. The cross-section in the middle of the points has the shape of a nearly isosceles triangle. The average length, width, thickness, and weight are 19.8cm, 11.9cm, 8.07cm, and 2.32kg respectively (Figure 2 c, d).

Crude chopping tools were made from quartz or quartzite pebbles, which had a large size and an oval shape. Flake scars are mainly found on one end. They were trimmed narrower on one side to make choppers or both sides to make chopping tools. Those tools often have a convex edge and a big handle that still keeps the original pebble cortex. The average length, width, thickness, and weight are 19.2cm, 11.7cm, 9.0cm, and 2.4kg respectively.

The tool-making technique in An Khe is different from that on other sites in Vietnam such as Do Mountain (Thanh Hoa province) and Xuan Loc (Dong Nai province). On those two sites, stone tools were made from surface basalt rocks. In Do Mountain, there are large-sized hand axes, rudimentary hand axes, crude hammerstones, Clactonian flakes, and multifacial stone nuclei. In Xuan Loc, meanwhile, there are small-sized hand axes and trihedral points; there are neither stone nuclei nor flakes. The age of those tool-making techniques is determined on the basis of the morphology of tools. For example, the stone tools in Do Mountain are estimated to date from 400,000 BP [15], and Xuan Loc from 500,000 BP [8].

Outside Vietnam, the Acheulean tool- making industry (France) is seen by scientists as manufacture characterised by bifaces and hand axes typical for the Palaeolithic period, which was previously determined to last from 500,000 to 300,000 BP [7] and has been recently determined to last from 1,700,000 to 300,000 BP [11]. The bifaces were made of flint, of which the two sides were knapped to create a thin edge and a pointed end; the handle is large and thick; and, they have an even body surface. The hand axes have different shapes, including a rectangle, a heart, an almond, a javelin dart, an egg, and eclipse shapes, of which the most typical are the shape of an almond and the shape of a javelin dart.

Different from the Acheulean hand axes, the An Khe hand axes were made of pebbles. The original cortex of the pebbles is still found in some parts of the hand axes. The handle is nearly round and large. Meanwhile, the Acheulean hand axes were made of sedimentary stone, particularly silica stone. The natural cortex of the stone was completely flaked off. They have a thin and bevelled handle. Large flake scars without any modification can be found on the An Khe hand axes, whereas, the Acheulean hand axes have only small flake scars modified by regular and well-proportioned knapping. The longitudinal section of the An Khe hand axes has the shape of a wedge, while the cross-section has a nearly oval shape. Meanwhile, the longitudinal section of the European Palaeolithic hand axes has the shape of a wedge, and the cross section almost has the shape of a lens. In general, the An Khe hand axes were cruder than the European ones, showing more ancient characteristics.

In Southeast Asia, the most ancient bifaces found in Indonesia bear some typical characteristics of the Acheulean industry that dates to around 0.8 million years before present. In this region, however, the mainstream technique is the manufacture of choppers and chopping tools [14].

In East Asia, Palaeolithic hand axes have been found in Dingcun, Hehe, Zhou Koudian, and especially Baise area (Guangxi province, China). There are 44 Palaeolithic sites located in five counties along the You river within the area of the Baise valley, including Baise, Tiandong, Tianyang, Pingguo, and Tianlin. The tools unearthed in those sites are classified to belong to the Baise tool-making technique. They include points, choppers, scrapers, bifaces, and hand axes, which were made of pebbles of a large size. They were knapped directly on stone anvils. Very few flakes have been found on those sites. As regards hand axes alone, they were found in four locations, including Yangshu, Nuolai, Nan Banshan, Pihong, which are located in the fourth platform of the You river and date back to the mid- Pleistocene. In 1993, a meteorite sample belonging to the Baise technique was found in Baigu in Dahe village. It dates to the period from 732,000 ± 39,000 BP, according to the absolute dating. Recently, another meteorite sample belonging to the Baise technique is determined to have an age of 803.000 ± 3.000 BP. Chinese archaeologists suppose that the Baise technique represents the most ancient Palaeolithic hand axe technique in East Asia [9]. The An Khe and the Baise techniques have many similarities in types and manufacturing ways. Different from the Acheulean industry in Europe, these two techniques may have the same age.

Russian and Vietnamese archaeologists have identified that the An Khe technique is characterised by a toolkit, consisting of crude chopping tools, trihedral points, and bifacial hand axes. Of those tools, the crude chopping tools have been mainly found in Asia; the bifacial hand axes are typical for the Palaeolithic tools in the West; and, the trihedral points most characterise the An Khe Palaeolithic tools.

Regarding the age, the sample coded 15.GD.M4.L1-2 found in Go Da dates back to 806,000 ± 22,000 BP and the sample coded 16.RT1.H1.F6.L2.2 found in Roc Tung dates back to 782,000 ± 20,000 BP, according to the Potassium-argon dating (K-Ar dating) conducted at the Laboratory of Isotope Geochemistry and Geochronology that belongs to the Institute of Geology of Ore Deposits, Petrography, Mineralogy, and Geochemistry (IGEM RAN), Russian Academy of Sciences. Thus, the An Khe technique dates to around 800,000 years before present.

As a result, the An Khe technique, of which the age is around 0.8 million years, was added by the Russian and Vietnamese archaeologists to the world map of biface industries [16].

The findings in the An Khe Palaeolithic sites changed the awareness of the history and life of Vietnamese ancestors. In principle, history is seen to start, when humans appeared. In the past, the history of Vietnam was supposed to start from the time of Homo erectus, whose fossils were discovered in Tham Khuyen and Tham Hai (Lang Son province) and date back to 0.5 million years ago. With the findings at the An Khe Palaeolithic site, however, the history of Vietnam has been determined to start earlier, at the time of about 0.8 million years ago. The inhabitants in that epoch were identified as Homo erectus (upright man). Consequently, An Khe is marked on the world map as one of the places that have kept the cultural traces of human ancestors. The An Khe toolmakers were, therefore, Homo erectus, the direct ancestors of Homo sapiens.

Due to the shortage of materials, for a long time, many people believed in the existence of a line proposed by H.L. Movius in 1948 that divided the Palaeolithic culture between the West and the East [13]. According to the Movius line, the West was popularly characterised by the Palaeolithic hand axes trimmed in a standard and well-proportioned way, illustrating the dynamism and progression. Meanwhile, the East was characterised by pebble chopping tools trimmed crudely according to the natural shape of the pebbles, illustrating the backwardness, stagnation, and conservatism without any contribution to the progression of humanity [12]. The discovery of the biface and hand axe technique in An Khe (Vietnam), Baise (China), and many other locations in Asia has repudiated the hypothesis mentioned above.

Over nearly half a century, most people believed that Africa was the origin of earliest humans, who then migrated and brought the technique of bifaces to Europe and Asia. The discovery of the Palaeolithic hand axes in An Khe is one of the grounds for reviewing the theory of evolution of Homo sapiens in various continents as well as the historical and cultural development in this region during the Palaeolithic Age.

4. Conclusion

In the context of the open-door policy and international integration, Vietnamese archaeologists set up and strengthened cooperation with many partners from different countries in the world. Particularly, the projects and programmes carried out in cooperation with the Soviet archaeologists in the past and the Russian ones at present have shown friendliness, sincerity, and good effects.

With a lofty friendship, Vietnamese archaeological researchers never forget the love and support provided by Russian people for Vietnamese as well as the heartfelt cooperation of the Soviet archaeological partners in general and Russian partners in particular with Vietnamese researchers and people. Owing to those cooperation programmes, Vietnamese archaeology has developed, clarifying further the national tradition and origin and contributing to the world archaeology. A recent outstanding achievement of the archaeological cooperation between Russia and Vietnam is the result of the research excavations at An Khe sites and Con Moong cave.

A standard stratum on the evolution of the prehistoric culture, showing the adaptation of humans to the environment and the community structure of the inhabitants during the period from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, has been disclosed by the excavations at Con Moong and its surrounding caves.

The discovery of the An Khe Palaeolithic technique has changed the consciousness of the history and life of Vietnamese ancestors. It helps to assert that the history of Vietnam started earlier, 0.8 million years ago. The An Khe Palaeolithic toolmakers were Homo erectus, the direct ancestors of modern humans. Thus, An Khe has been added to the world map as a location keeping the cultural traces of human ancestors. The discovery of the Early Palaeolithic hand axes in An Khe is seen as one of the grounds for reviewing the theory of evolution of Homo sapiens in various continents as well as the historical and cultural development in this region during the Early Palaeolithic Age.

Vietnamese archaeology has developed greatly and become a reliable partner in many archaeological cooperation programmes with other countries in the world, including Russia. In 2018, a research project co-funded by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR) and the Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences (VASS) was launched with the title “Fundamental Issues of the Stone Age Vietnam in the Context of Stone Age Indochina”. This project is a sign that the archaeological cooperation between Russia and Vietnam will be strengthened and spread to other countries in Indochina and Southeast Asia.

Notes

1 The paper was published in Vietnamese in: Khảo cổ học, số 3, 2018. Translated by Nguyen Tuan Sinh, edited by Etienne Mahler.

References

[1] Ngô Sĩ Hồng (1982), “Khảo cổ học Xô viết và văn hóa Xkip”, Tạp chí Khảo cổ học, số 4. [Ngo Si Hong (1982), “Soviet Archaeology and Scythian Culture”, Journal of Archaeology, No. 4].

[2] Phạm Lý Hương (1982), “Khảo cổ học Xô viết và Thời đại Đá ở Trung Á”, Tạp chí Khảo cổ học, số 2. [Pham Ly Huong (1982), “Soviet Archaeology and Stone Age in Central Asia”, Journal of Archaeology, No. 4].

[3] Nguyễn Khắc Sử (1982), “Khảo cổ học Xô viết và thời đại Đá cũ ở Liên Xô”, Tạp chí Khảo cổ học, số 4. [Nguyen Khac Su (1982), “Soviet Archaeology and Palaeolithic Age in USSR”, Journal of Archaeology, No. 4].

[4] Nguyễn Khắc Sử (2017), “Kỹ nghệ sơ kỳ Đá cũ An Khê với lịch sử thời kỳ nguyên thủy Việt Nam”, Tạp chí Khảo cổ học, số 2. [Nguyen Khac Su (2017), “Early Palaeolithic Industry of An Khe and Primitive Period in Vietnam”, Journal of Archaeology, No. 2].

[5] Chử Văn Tần (1982), “Khảo cổ học Xô viết - một mẫu hình khoa học tiên tiến”, Tạp chí Khảo cổ học, số 4. [Chu Van Tan (1982), “Soviet Archaeology: An Advanced Scientific Model”, Journal of Archaeology, No. 4].

[6] Phạm Huy Thông (1982), “Diễn văn Khai mạc Hội nghị”, Tạp chí Khảo cổ học, số 4. [Pham Huy Thong (1982), “Conference Opening Speech”, Journal of Archaeology, No. 4].

[7] Derevianko, A.P. (2014), Bifacial Industry in East and Southeast Asia, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS Press Novosibirsk, Russia.

[8] Movius, H. (1948), "The Lower Palaeolithic Cultures of Southern and Eastern Asia", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, No. 38 (4), pp.330-420.

[9] Movius, H. (1949), New Palaeolithic Cultures of Southern and Eastern Asia, Philasophia.

[10] Nguyen Khac Su, Nguyen Gia Doi (2015), “System of Palaeolithic Locations in the Upper Ba River”, Vietnam Social Sciences, No. 4.

[11] Simanjuntak, T. (2008), "Acheulean Tools in Indonesia Palaeolithic", Paper Presented on the International Seminar on Diversity and Variability in the East Asia Palaeolithic: Toward an Improved Understanding, Seoul, Korea, p.421.

[12] Bordes François (1961), "Bifaces des Types Classiques", Typologie du Paléolithique ancien et moyen, Impriméries Delmas, Bordeaux, pp.57-66.

[13] Guang Mao Xie, Erika, Bodin (2007), Les Inductries Paleolithiques de Basin de Bose (Chine de Sud), L’Anthropologie, No. 111, pp.182-206.

[14] Saurin, E. (1971), Les Paléolithiques de environs de Xuan Loc, Bulletin de la Société des Etudes Indochinoise, Vol. 46, pp.2-22.

[15] БОРИСКОВСКИЙ П.И. (1966), Первобытное прощлое Вьетнама, Москва - Λенинград.

[16] ДЕРЕВЯНКО, А.П., Н.Х. ШУ, А.А. ЦЫБАНКОВ, Н.З. ДОЙ (2016), Возникновение бифасиальной индастрии в Восточной и Юго- Васточной Азии, Новосибирск Издательство ИАЭТ СОРАН, ctp.59.

[17] ПРЕЗИДИУМ РОССИЙСКОЙ АКАДЕМИИ НАУК (2014), Полная академическая история Вьетнама, в шести томах, том I, древность и раннее средневековье (конец 4 - начало 3 тыс. до н.э. - 1010 г. э.), Москва.

Sources cited: Vietnam Social Sciences, No. 1 (189) - 2019