Ngo Ngan Ha*

Abstract: This paper provides an account of the perception of men in the Red River Delta (RRD) towards the management of the household budget and the decision making progress in the family based on the results of a doctoral thesis on fatherhood and masculinity. Women continued to be the ‘cashier’ in the family as they had been in the traditional Vietnamese society. The power to keep the money for the household also brought women the right to decide day-to-day expenditures. However, this did not mean that women were enjoying equality with men in financial matters. Although quantitative data showed a great sharing between spouses in deciding important matters of the family, information collected from interviews with men revealed rather different findings. Men reported ‘letting’ their wives control the family budget and decide small and routine purchases in order to stay away from housework and protect their masculinity. When it comes to other big purchases/investments and important decisions of the family, men reported that they were always the decision makers, whether their wives agreed with them or not.

Key words: Gender; Gender role; Gender inequality; Family; Masculinity; Division of household labour.

1. Introduction

The topic of gender inequality in the Vietnamese family has been researched and well documented in various books and papers over the last few decades (Pham, 1999; Knodel et al., 2005; Teerawichitchainan et al., 2010; Vu et al., 2013). Beside some popular topics such as the division of household labour or gender wage gap, gender inequality could also be found in the limited access of women to, and control over, productive resources. Doi Moi, with its de-collectivisation process, has transferred the rights to use land, which were previously under the control of the co-operatives, to households and individuals. The 1993 Land Law allowed name of the owner of the land to be stated on the land use certificate. However, as there was only room for one name on the certificate, it was usually the name of the household head (who in most cases was male) that appeared on the Land Tenure Certificate (LTC). This means “wives’ rights to land and housing may become highly contingent” (Jacobs, 2008: 28). Ten years after the reform, data reveals that only 10-12% of land use certificates were issued to women (World Bank, 2011: 25). The 2003 Land Law has made a reformulation by allowing both husband and wife’s names to be listed on the LTC. Despite this, the majority of LTCs in 2008 still did not include women’s name as 62% of them were accounted for male-only holders (Jones & Tran, 2012: 2). Female-only holders made up only one fifth (20%) of LTCs and the rest 18% belonged to joint holders (ibid.).

As argued by Jacobs (2008), women’s work in collectives was visible during the time of agricultural collectivisation as it was rewarded with points. After Doi Moi, the Vietnamese family, especially rural families, resumed their economic functions, which had been administered earlier by the cooperatives (Resurreccion & Ha, 2007). As a result, women’s contributions to the family income became more difficult to see and calculate in cash (Le, 2004). Even though women are still responsible for holding ‘the key to the cash trunk’ of the family as they did in the past (Knodel et al., 2005; Teerawichitchainan et al., 2010)(1), cash management does not entail the right to decide on expenditures. In fact, husbands always have the decisive voice in big expenditures of the family such as house building or repair, or purchasing great value things. Meanwhile, wives are in charge of small expenditures, for instance, buying foodstuff for daily use of the household, paying children’s education fees, electricity and water bills (Le, 2004). With most LTCs possessed by men, women, especially in rural areas, become more subordinated to men. Moreover, de-collectivisation also reinforced the importance of family lineage and intensified the preference for sons (Jacobs, 2008). “Traditional norms of domesticity have come to replace former socialist ethics of collective participation and heroism” with the revived emphasis on the male-centred family (Resurreccion & Ha, 2007: 212). Consequently, women’s work and role were again considered as inferior to men’s.

Using data collected from 122 questionnaires and 30 semi-structured interviews with men from Ha Noi and Ha Nam, two provinces in the RRD, this research was conducted in order to understand household budget management and decision making in the family in the RRD from men’s perspective. In order to recruit an appropriate sample, the multi-stage cluster sample method was employed. Two chosen wards in Ha Noi are Lang Ha and Tho Quan (both are from Dong Da district), and one chosen commune in Ha Nam is Dong Du (Binh Luc district). This research was a part of my doctoral thesis, which was successfully defended at Manchester Metropolitan University, the United Kingdom, in September 2015.

2. Men’s view on the person who manages the budget of the family

Traditionally, Vietnamese wives enjoyed a great share of domestic power by holding the key of the “family’s cash trunk” (Pham, 1999: 39). This continued to be true according to research on the division of household labour in Vietnam (Teerawichtchainan et al., 2010; Vu et al., 2013). Findings from my research matched well with the literature as the majority of respondents (85.2%) reported that their partners manage the family’s finances. Meanwhile, only 11.5% claimed to control the household’s budget and the other 3.3% did it together with their wives. Quantitative data showed a statistically significant relationship between respondents’ residence and how their families’ finances were managed.(2) As reported by men, urban women were more likely to handle their family’s fund than were their rural counterparts. One quarter of respondents from Ha Nam indicated that they managed the money of their families compared to only 5% of men from Ha Noi.

However, analysis from semi-structured interviews showed slightly different findings with none of the interviewees reporting controlling the family’s budget. Some claimed that their families had a “common budget”, and either the husband or the wife “could withdraw money to spend” whenever they wanted (Thong(3), 52, farmer, Ha Nam). Tung, a 37-year-old trader from Ha Noi noted, “We just put all the money we earn in the safe. If my wife or I need to spend on something, we simply get money from the safe”.

Other men said that their wives were “the cashier” who was “in charge of the family’s budget and “pays for everything no matter if it is a big or small purchase”(4) (Chien, 53, farmer, Ha Nam). Kim, a 60-year-old retired manager from Ha Noi, did not even know exactly how much money they had:

“…I just give her (his wife) all the money I have earned and she will decide whether to save it in the bank, or to buy gold or US dollars and then keep them in the safe. It is up to her. I do not care too much about it. She usually counts everything in the safe about 3-4 times per year then tells me how much money we own approximately”.

Reasons given by men to explain the dominance of women in managing the household budget varied from “women are very good in spending and saving money” (Hau, 44, army officer, Ha Noi), to “men only manage large and important matters” (Cuong, 34, Commune Officer, Ha Nam), or “if I keep money, my wife might distrust me” (Chien, 53, farmer, Ha Nam). Chien explained further that even though he earned most of the money in his family, he let his wife keep all of it since “money should be brought together as a whole otherwise it would be very complicated to manage”.

Chien’s view on the necessity of bringing money in the family together as a whole was opposed to Nhu’s, a 54-year-old artisan living in the same village in Ha Nam. Nhu earned his living by repairing electric appliances such as fans, televisions, radios of the villagers, while his wife was a peasant farmer. They had two daughters and one son, but all of their children stayed in Ha Noi at the time of interview. Nhu told me that in his family he kept the money that he earned, and his wife kept the money that she earned. According to him, managing the money this way “was very convenient” since:

Nhu: “…she can spend the money that she gets from selling chickens, pigs, or rice to buy fertilizer, seeds, or breeding stock. Likewise, I do not need to ask her if I want to buy some screws or a coil of copper wire”.

Ha: “How about mutual spending in the family such as buying food or other valuable possessions?”

Nhu: “She is usually in charge of buying food with her own money. I will give her money when she runs out of it or when we need to send money to our son who is studying in Ha Noi. Similarly, if I want to buy a motorbike and I am short of a few million Vietnamese dongs, I will borrow hers.”

Nhu saw the way he and his wife managed money in their family as a “mutual respect” since no one could control all of the other’s money. As he indicated, sharing the responsibility of managing the family budget also meant sharing responsibilities for household tasks. He believed that “only men who do not want to be involved in domestic affairs give their partners all the money they earn”. However, findings from interviews with other participants showed that men’s involvement in domestic labour did not depend on how their family’s budget was managed. For instance, Cuong, a Commune Officer from Ha Nam, on the one hand, claimed that his wife “holds the key of the family’s cash trunk”, but on the other hand also insisted that he shared housework equally with his wife. Other respondents who reported letting their partners manage the household budget also indicated doing housework to a certain extent. Therefore, it could be said that the neglect by men of family finance management did not signal lesser involvement in domestic affairs. The question raised here is: Does keeping the budget mean controlling it? Within this research, more than 85% of women were reported to hold the purse strings, but could they actually control expenditure? The following section of this article will explore the different roles of wives and husbands in making important decisions in the family such as purchasing valuable possessions, making investment, or children’s education/career.

3. Husband’s and wife’s decision making powers on family matters

In the family, there are many important matters requiring the couple to make timely and appropriate decisions, for instance decisions over spending big amounts of money on buying/selling valuable possessions, building/repairing the house, or family investments. There are also matters related to children such as their education or marriages. It depends on each couple whether they will discuss these things together carefully before reaching a final decision. The involvement of the wife and the husband in decision making in the family reflects the balance of power between them (Blood & Wolfe, 1960). Exploring this progress could help us locate the real status and power of each household member (Le, 2009).

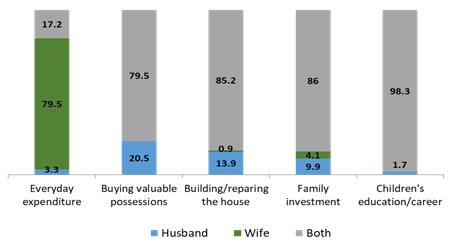

Firgure 1. The person that makes the decisions in the family (%)

Within this research, women were reported to have more power than their husbands in deciding things related to day-to-day spending. As can be seen in Figure 1(5), approximately 80% of respondents indicated that their female partners were largely in charge of purchasing small daily things for the family. Meanwhile, important decisions were reported to be taken mostly by both spouses. Regardless of demographic differences, around 80% of men mentioned that big decisions related to buying expensive properties such as a motorbike/car/house (79.5%), building/repairing the house (85.2%), family’s investment in business and production (86%), or children’s education/career (98.3%), were discussed thoroughly between spouses before being made. These proportions were relatively high, and often two or three times higher than results from existing studies, which might suggest a growing involvement of women in deciding important matters of the family, at least within this sample.

The power of women to decide day-to-day expenditure in the family could be seen as the result of their dominance in both managing the household budget and everyday grocery shopping.(6) This was also echoed from semi-structured interviews, in which all men claimed that their wives managed expenditure such as purchase of foodstuffs for the family daily’s use, children’s school fees and electric/water/internet bills. However, this did not mean that women enjoyed equality with men in financial matters. In interviewees’ views, women controlled the everyday household expenses because “women are in charge of housework so they need to spend money on foods and stuffs such as toothpaste, washing powder, etc. for that” (Hanh, 31, banker, Ha Noi); or “men should not be involved in spending tiny amounts of money like that” (Phuong, 46, farmer, Ha Nam). Tung, a 37-year-old trader from Ha Noi explained that since his wife had “a better liking” than him, “it is usually for her to buy clothes and small things for the family”. Interestingly, these comments provided implicit reasons for the lesser involvement of men in controlling everyday expenditure. It might be that men ‘allowed’ their wives decide this matter in order to stay away from housework or to protect their manhood.

Within this research, while quantitative data showed a great deal of sharing between husbands and wives in deciding important matters of the family, information gathered from in-depth-interviews with men offered rather different results. Most interviewees recognised that they consulted with their partners thoroughly before making important decisions. They talked about the 'equality' between husbands and wives, or the 'right' of women in making decisions for the family. However, understanding that household decision-making is never a straightforward process, whereby consensus might be reached with negotiation, I asked interviewees some more questions, such as How would you reach agreement if one held an opposing view? and Whose opinion has more weight? It turns out that, as found by previous research (Pham, 1999; Werner, 2009), men were always the primary decision-makers. Tuyen, a 48-year-old electrician from Ha Nam said: "if there is any disagreement between me and my wife, final decisions are always taken by me”. He added that from the very first day of their marriage, he had been the main decision maker of the family and his wife “had to listen” to him even if she disagreed with him. This view was shared widely by other respondents. The involvement of women in the decision making progress might be reported to be quite equal as pointed out by quantitative data, yet men claimed that they took their wives’ opinion “as references” and they “still make final decisions” (Trung, 42, Government Officer, Ha Noi). Similarly, when Tung, a 37-year-old trader from Ha Noi, wanted to buy or sell a property, he “would list out the benefits and losses of that business”. Then, Tung and his wife “would discuss carefully about it”. “She could raise as many ideas as she wants but eventually she usually asks me to consider everything and make the decision”, Tung expressed.

During interviews, men’s confidence of their supremacy over women in making important decisions for the family was evident. All respondents, regardless of their demographic characteristic differences, claimed to have the ultimately decisive voice in most cases, from buying valuable things to investing money in family business/production or children’s education/career. Women might keep the money but they just played the role of “cashier” in the family. Cash management does not entail the right to decide on every expenditure. When the husband decided to buy an expensive possession, a motorbike for instance, the spouses would “go to the store together” and the wife had the responsibility to “pay the money to the seller”(7) (Chien, 53, farmer, Ha Nam). Men also mentioned their important roles in deciding matters related to their children’s future. Women might pay children’s school fees but it was men who oriented their offspring’s education and career. Khoi, a 55-year-old manager from Ha Noi, proudly described his impact on his daughter’s education:

“….Since Thuy (his daughter) was small, I tried to choose the best school for her to go. Schools in our area were usually not so good, so I had to make use of my acquaintances to make applications for her to good schools from other areas. My wife did not know many people so she could not do that thing. When Thuy graduated from high school two years ago, I decided to send her to Australia to study for an undergraduate degree. My wife opposed that idea initially because she worried that it would cost us a lot of money. But I determined that I could earn enough money to support her. And now Thuy is in her third year at the University of Queensland.”

According to the Resource Theory which was developed by Blood and Wolfe in 1960, the relative power of husband and wife is determined by their contributions of resources, including education, earnings, and occupational prestige, to the relationship. The spouse who provides the most will enjoy the greater decision-making power. Later, Liat Kulik (1999) added that health and energy resources, psychological resources (problem-solving and social skills), and social resources (access to social networks) play important roles in marital power as well. In Khoi’s case, which was mentioned above, it could be seen that his better income and social networks provided him with more favourable conditions than his wife to make decisions about their daughter’s education. Likewise, six other respondents believed that their dominance in decision making came naturally from their greater contribution in terms of income. “I am the main financial provider of the family now so I certainly orientate the main decisions of the family”, Son, a 30-year-old trader from Ha Noi stressed. A similar comment came from Chien, a 53-year-old farmer in Ha Nam: “I am the main financial provider of the family so my wife and my children always listen to me”. Chien also held that since he was better than his wife “in contriving things” (psychological resources), it must be him “who made final decisions”.

Besides, the power of men in deciding important matters in the household, in some cases, was also reported to be derived from the traditional view of gender roles. Nine respondents referred to their traditional role as the “core pillar” in the family. “I am the breadwinner and the pillar of my family so my responsibility is deciding everything” (Hung, 40, Commune Officer, Ha Nam). Tung, a participant from Ha Noi, said “…the decision is mine simply because I am the pillar of the house”. Another man told me that “a proper man should be mentally strong and decisive to decide important things in the family” (Kim, 60, retired, Ha Noi). Clearly, the Resource Theory has not considered influences of the culture and gender ideology on the balance of power between spouses in the decision making process. In a patriarchal society like Vietnam, women might not have the right to decide although they contribute equally or even contribute more resources to the family than their husbands. For instance, Tung was a trader who ran a fashion shop and a travel agency with his wife in Ha Noi. They both graduated from the same university, had the same jobs and shared the income from their business equally. However, being considered as the “pillar of the house”, Tung was still the main decision-maker in their house. In this case, it seems that gender role had greater impact than other resources in the decision making process.

4. Discussion

Within this research, wives were said by the male respondents to manage household finances and dominate day-to-day decision making such as purchasing small things or buying groceries. This matches the findings of Vu et al. (2013). However, while this might superficially appear to empower women, giving them more say and status within the household, in Vietnam, controlling the family budget and making decisions on household expenditures are seen more as domestic chores than a process of empowerment. Thus, it appears that the patriarchal gender regime puts women in the role of decision maker for practical purposes (for example, from the man’s gender prejudiced point of view sparing him the time of having to make these decisions) but uses ideology (i.e. diminishing the status of such tasks) to ensure continued male hegemony.

When it comes to making decisions in the household that are considered more significant, such as large expenditures or children’s education and career, participants report that they always have greater power than their wives. This confirms the findings of research by Knodel et al., (2005), Tran (2009), Le (2009), Pham (2008) and Vu (2009). Although most respondents claimed to discuss with their wives before making important decisions – a common trend that was noted in previous studies (Vu, 2009; Tran, 2009; Vu et al., 2013) - husbands are usually the primary decision makers in the family. All informants from semi-structured interviews asserted that they always had the final decisive voice in every important decision of the family, regardless of any possible disagreement from wives. What has been discovered here is that sometimes men use various means, such a discussions and agreeing to their wives having minor decision making powers, in order to give the impression that the family has something of an, albeit uneven, democratic basis. In fact they might often actually believing this equality themselves. Nevertheless, in practical matters men still act as patriarchal leaders of their households in the RRD in any case. On the one hand, the husbands are fully aware of this patriarchy role, but on the other hand, some see themselves as ‘fair’, as good husbands, and even as progressive, for including their wives with some say in household matters. Along with some male increases in performing household labour, this ‘mixing’ of old gender roles can be seen as progressive. It does challenge older and strict Confucian gender boundaries. But it also implicitly reinforces those gender boundaries to some degree, as this new way of ‘doing gender’ is still controlled by men, and still reinforces their male hegemony, because they are the ones who choose to ‘help’ with ‘female’ tasks, and who choose to ‘allow’ women some discussion on ‘male’ matters. Thus, the old gender based power divisions, and the old Confucian categories of male and female spheres, are partly maintained, even by the processes that are seeming to undermine them. How this dialectical process will unfold, either for or against gender equality, is an important area for potential future research to consider.

In the meantime, the practical reality is that it seems that women’s voices in household decision-making processes are still not much appreciated. Women might negotiate with their husbands, but their opinions are secondary, whereas men’s are decisive. However, since this research focuses on men only, it could not assess women’s positions and their influences in negotiations. This, too, is an important area for potential future research that has been indicated by this study.

Qualitative analysis from this research partially agrees with Resource Theory (Blood & Wolfe, 1960; Kulik, 1999), in that seven informants referred to their greater financial contributions to the family income as the natural and direct reason that brought them power in making household decisions. In a study with South Asian couples who migrated to the US, George (2005: 27) suggests that the narrower is the wage gap between the spouses, the more authority women have, while previous research in Vietnam has argued that levels of economic contribution affects wives’ bargaining power in the household decision-making process. Once the wives’ contribution for their household income increased, their status within the family would be elevated and they would gain more rights in making decisions (Nguyen, 2003: 85; Pham, 2008; Hoang & Yeoh, 2011). Without speaking to the participants’ wives, it is difficult to assess their real levels of influence in household decision making. Even then, we will still only be looking at what people say, and not necessarily the empirical realities behind what they say. What I have found, however, is that the male respondents largely believed that their higher earnings justified more domestic power. And as the inequality in earnings between women and men in Vietnam is significant, with women paid an overall average of only 75% of men’s wages in 2009 (World Bank, 2011: 52), it appears that gender inequality in the household, and wage inequality at work, are ideologically and practically interconnected. Lower wages for women at work supports, at least in ideological terms, domestic power for men. However, it is possible that in the future higher household incomes will be more valuable to families, and there could be a conflict of interests for men between having diminishing power at home, and having money in the household account. How this might affect future gender perceptions and relations is an area of potential future research. However, while the gender pay gap declined during the period 1999-2011 globally, it increased 2% in Vietnam (ILO, 2012). Hence, this economic basis of gender inequality at home does not appear likely to change in the near future.

5. Conclusion

Overall, this article provided some insights into the relationship between husbands and wives in managing the household budget and deciding important affairs. A large percentage of women were reported to be the ‘cashier’ of the family, but this did not result in equality between spouses in spending money. In fact, women were regarded as the money keeper and payer of the family rather than the spender or buyer. They decided most small and daily expenditures in the family. However, qualitative data suggested that men ‘let’ women manage everyday household expenses in order to avoid being involved in housework and/or to protect their masculinity. Meanwhile, large expenditures in the family were all decided by husbands. Men also had greater impact in orientating their children’s education and career. Although most respondents claimed to consult with their wives before taking these important decisions, men were always the final decision makers. This lower decision-making power of women, in some cases, was understood to be derived from the fewer financial resources which they contributed to the family.

Furthermore, this research revealed that men’s financial advantage is far from being the only reason that men continue to enjoy authority in the home. In some cases, the husband was still the decision-maker, even though the wife contributed an equal amount financially to the family, or even more than the husband did. The reason for this was revealed to be an enduring and strong belief that the male ‘role’ is to be the ‘undisputed head’ of the family. (Although, this research cannot reveal whether the wives agreed with this idea, or simply had no choice but to accept it. We only know that respondents believed this.) Nine men saw their identities as being attached to their patriarchal roles as the ‘core pillar’ of the household, while some others believed in the characterisation of masculinity as being mentally strong and decisive, which means, in real terms, being in control of the household and making all of its important decisions. Without doing this, a man could not really be a man. This is not only an enduring gender issue in Vietnam, a country that has been deeply influenced by Confucian perceptions for centuries, but also an apparently universal one. Some feminists have also previously linked patriarchal power with men’s dominance in making household decisions (Pahl, 1989; Morris, 1990). Therefore, if Vietnam is to achieve gender equality, efforts must be made to empower women with more authority in household decision-making. This research found that such empowerment needs to be based on practical factors - particularly wage equality - and also ideological factors, namely the transformation of patriarchal beliefs into a more gender equitable view of household life.n

Endnotes

* Ngo Ngan Ha, Ph.D, Ho Chi Minh National Academy of Politics

(1) More than two thirds (approximately 70%) of the participants in the study of Teerawichitchainan et al. reported that the wife managed the household budget a lot (2010: 15). Data from the Survey on the Vietnamese family 2006 also indicated that 85.2% of women made day-to-day decisions and purchases of the family (Tran, 2009: 34)

(2) Chi-square value = 9.503; df = 2; p value = 0.009; Pearson’s r = - 0.216.

(3) From here on, the names of respondents in this article have been replaced with pseudonyms.

(4) By using the word “pay”, it looks like Chien wanted to stress his wife’s role as a budget keeper and money payer rather than a buyer or a spender.

(5) The Cronbach’s alpha of these items is 0.71, which indicates a good internal consistence of these questions (Bryman, 2012).

(6) As found out earlier in this chapter, 88.5% and 85.2% of respondents reported their wives taking care of most of the grocery shopping and managing household budget respectively.

(7) By using the word “pay”, it looks like Chien wanted to stress his wife’s role in keeping and paying money, rather than in deciding on what to buy.

References

Blood, R. O. and Wolfe, D. M. (1960). Husbands and Wives: The Dynamics of Married Living. Free Press.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods. 4th ed.: Oxford University Press.

George, S. M. (2005). When women come first: Gender and class in transnational migration. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hoang, L. A. and Yeoh, B. S. A. (2011). 'Breadwinning wives and 'left-behind' husbands: Men and masculinities in the Vietnamese transnational family.' Gender & Society, 25 pp. 717-739.

ILO. (2012). Global Wage Report 2012-13: Wages and Equitable Growth.

Jacobs, S. (2008). 'Doi Moi and its Discontents: Gender, Liberalisation, and Decollectivisation in rural Viet Nam.' Journal of Workplace Rights, 13(1) pp. 17-39.

Jones, N. and Tran, A. V. T. (2012). The politics of gender and social protection in Viet Nam: opportunities and challenges for a transformative approach. London: Institute for Family and Gender Studies, Overseas Development Institute.

Knodel, J., Vu, L. M., Jayakody, R. and Vu, H. T. (2005). 'Gender roles in the family: Change and Stability in Vietnam.' Asian Population Studies, 1(1) pp. 69-92.

Kulik, L. (1999). 'Marital Power Relations, Resources and Gender Role Ideology: A Multivariate Model for Assessing Effect.' Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 30(2) pp. 189-206.

Le, T. (2004). Marriage and the family in Viet Nam today. Ha Noi: The Gioi Publishers.

Le, T. (2009). 'Family labour division and decision-making (Case studies in Hung Yen and Ha Noi provinces).' Journal of Family and Gender Studies, 19(5) pp. 16-25.

Morris, L. (1990). The Working of the Household. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Nguyen, D. T. (2003). Household economy and social relations in the rural areas of the Red River Delta in the transitional period (Kinh te ho gia dinh va cac quan he xa hoi o nong thon dong bang song Hong trong thoi ky doi moi). Hanoi: Social Sciences Publishing House.

Pahl, J. (1989). Money and Marriage. London: Macmillan.

Pham, B. V. (1999). The Vietnamese Family in Change: The case of the Red River Delta. Surrey: Curzon Press.

Pham, T. H. (2008). 'Power relations between husbands and wives in rural families.' Vietnam Journal of Family and Gender Studies, 3(1) pp. 15-30.

Resurreccion, B. P. and Ha, K. V. T. (2007). 'Able to come and go: Reproducing gender in female rural-urban migration in the Red River Delta.' Population, Space and Place, 13 pp. 211-224.

Teerawichitchainan, B., Knodel, J., Vu, L. M. and Vu, H. T. (2010). 'The Gender Division of Household Labour in Vietnam: Cohort Trends and Regional Variations.' Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41(1) pp. 57-85.

Tran, N. T. C. (2009). 'Husband's and wife's decision-making powers on family matters.' Journal of Family and Gender Studies, 19(4) pp. 31-43.

Vu, T. T. (2009). 'Gender inequalities between wife and husband in Vietnam rural families.' Vietnamese Journal of Family and Gender Studies, 19(1) pp. 35-46.

Vu, L. M., Trinh, Q. T., Nguyen, T. H., Nguyen, T. B. K. and Dang, T. H. V. (2013). 'Labour division and decision making in the Northen Delta rural families.' Journal of Family and Gender Studies, 23(1) pp. 3-16.

Werner, J. (2009). Gender, Household and State in Post-Revolutionary Vietnam. Oxford: Routledge.

World Bank. (2011). Vietnam - Country gender assessment. Ha Noi.

Sources cited: Vietnam Journal of Family and Gender Studies. Vol. 14, No. 2, 2019, p. 17-29