Nguyen Ha Dong*

Abstract: The paper explores love and marriage in the rural North of Vietnam from 1976 to 1986 under the impact of individualism and collectivism using the data from the survey ‘The Northern rural family in the 1976-1986 period’ conducted by the Institute for Family and Gender Studies in 2018. The result shows that the traditional marriage pattern is transforming into a more modern one while the collective influences remarkably remain. The marriage pattern is the combination of traditional features with modern characteristics even though the former seems to be in favor of. The paper contributes more evidence for Triandis’s perspective (1995) that collectivism and individualism are able to parallel exist if having an appropriate combination. It is an effective w7ay to protect the harmony in the families and to adapt with the particular context of Vietnam before Doi Moi.

Key words: Love marriage; Arranged marriage; Collectivism; Individualism.

1. Background

After the unification, Vietnam started to build a centrally planned economy in the whole country. From 1976 to 1986, the agricultural collectivization was dramatically accelerated, thereby, a vast majority of rural locals became members of different co-operatives (Kerkvliet, 2000). Co-operatives in rural areas not only were economic units but also controlled rural people’s political, social and cultural activities (Phan Dai Doan, 2001). However, the 1976-1986 is also a period of severe economic crisis in Vietnam. Aid reductions, the withdrawal of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and China governments, the US embargo in lieu of aid provision as well as the impact of the 1979 border war with China, exacerbated the difficulties in the economy and people’s living conditions over this period (Dang Phong, 2013: 28-35).

In parallel, legal policies in the 1976-1986 continued to state the freedom in love and marriage of both men and women. After the Law on Marriage and Family 1959 – the first law on marriage and family in Vietnam – the 1980 Constitution reasserts the freedom in marriage and the spousal equal rights (Article 64).

The dramatic changes in the political, economic and cultural life of the country during 1976-1986 had a substantial impact on marriage patterns over the same period. The transformation from parentally-arranged marriage to love marriage is described in some research studies (Khuat Thu Hong, 1994; Le Ngoc Van, 2007; Nguyen Huu Minh, 1999). The increase in individual freedom of marriage choice from mate searching to marriage decision was observed during 1976-1986 . For example, the research study on rural families in the transition conducted from 2004 to 2008 in Yen Bai, Thua Thien Hue, Tien Giang and Ha Nam provinces shows that directly meeting sharply increased from 38.3% before 1975 to 48.4% during 1976-1986 while those through an introduction significantly declined (Le Ngoc Van, 2011).

Marriage decision maker is seen as one of the crucial indicators to evaluate the marriage and family changes (Vu Tuan Huy, 1995). The marriage pattern in the 1976-1986 period continued to increase individuals’ freedom in spousal choice which is represented in all social groups from rural to urban areas, who either follow or do not follow Christian, living in either nuclear or extended family (Mai Van Hai, 2004; Nguyen Huu Minh, 1999; Nguyen Huu Minh, 2008). According to the ‘Nation-wide Survey on the Family in Vietnam 2006’, the number of individuals choosing their spouse - with parents’ approval - increased from 57.7% in the period before 1975 to 70.1% from 1976 to 1986 (Le Ngoc Van, 2012).

Despite the increase of individual freedom, parents remain to play a remarkable role in their adult children’ marriage decision (Nguyen Huu Minh, 2008; Vu Tuan Huy, 2004: 73). Young people who completely decide their marriage by themselves accounts for a small percentage (Le Ngoc Van, 2012) and mostly occurs when brides and grooms gett married late or when their parents are very old or passed away (Vu Tuan Huy, 2004: 73). This is seen as an effective way to increase the consensus and integration within family members (Nguyen Huu Minh, 1999; Nguyen Huu Minh, 2008).

The prevalent marriage pattern in the 1976-1986 is the involvement of both parents and individuals in the marriage decision which the latter summit the proposal (Le Ngoc Van, 2012; Nguyen Huu Minh, 1999; Nguyen Huu Minh, 2008; Vu Tuan Huy, 2004). The marriage is still an important event for the whole family and lineages. The results of the ‘Nation-wide Survey on the Family in Vietnam 2006’ shows that the proportion of respondents choosing their spouse with their parents’ approval accounts for 70.1% of the total participants marrying between 1976-1986 (Le Ngoc Van, 2012).

Another concern related to marriage changes in the 1976-1986 period is the substantial role of individuals’ working offices or political-social organizations. They are able to allow or decline their employees’ marriage plans based on the balance of the political position between the couples’ families. This influence becomes more significant in rural areas (Belanger & Khuat Thu Hong, 1995).

Despite a number of research studies on marriage changes in Vietnam in the period of 1976-1976, there is a lack of studies exploring key features of dating time, as well as analysing marriage changes under the individualistic and collectivistic approach. This paper aims to investigate love and marriage in the rural North of Vietnam from 1976 to 1986 under the impact of individualism and collectivism using the data from the survey ‘The Northern rural family in the 1976-1986

period’ conducted by the Institute for Family and Gender Studies in 2018. Based on this dataset, the paper focuses on individual‘s freedom in the marriage process and then, the impacts of collectives on dating and marriage decision.

2. Theoretical approach

The concept of individualism and collectivism is formally named the first time by Hofstede in 1980. He defines that the former goes along with societies in which the ties between individuals are loosen, conversely, the latter is popular in societies in which people strongly integrated with social groups protecting them throughout their life time (Hofstede, 1980: 51 cited in Triandis & Gelfand, 2012). These two concepts can apply for both individual and social levels. If a vast majority of citizen in a society are individualistic or collectivistic, that society would have collectivistic or individualistic tendency, respectively (Hui & Triandis, 1986). Collectivism, as Triandis generated, is universally emphasised on connection among members within groups and prioritizing collective goals over individual goals. In contrast, individualism focuses on rationally analysis in advantages and disadvantages when collaborating with other person or groups as well as preference for individual goal over collective goals (Triandis, 1995: 3; 43-44). Individualistic or collectivistic tendency of each person depends on some impact factors including age, social class, education achievement or job (Triandis, 1995: 61-66).

Individualistic or collectivistic tendency is a crucial cultural factor determining in parents‘ influence on individuals’ spousal choice (Buunk et. al., 2010). Love marriage is the common marriage pattern in individualistic societies while parentally arranged marriage is typical for collectivistic societies such as China or India(1) (Dion & Dion, 1993). In such countries, marriage is viewed as the collaboration between two families or two lineages in order to maintain families‘ the wealth and prosperity in lieu of the integration of two individuals (Medora, 2003; Xia & Zhou, 2003). Notwithstanding, in tandem with the universal industrialisation, Goode (1963) predicted the freedom of mate choice in societies strongly influenced by collectivistic cultures such as China, India or Japan since the 1960s. Then, the transformation from parentally-arranged marriage to love marriage is evidenced in empirical research studies in Asian countries. For instance, the number of love marriage steadily increases during some last decades in the 20 century in Japan (Fukada, 1991 cited in Dion & Dion, 1993). Similarly, the shift from arranged marriage to love marriage is apparently observed in China. From the dominance in the marriage pattern in the pre-1949 period, the traditional arranged marriage dramatically reduced to less than 10% in the end of the 1980s; the percentage of people who directly met their spouse washigher than those through an introduction; those introduced by peers were more than by parents; those having romantic relationships or dates prior to marriage increased (Xiaohe & Whyte, 1990).

However, the transformation from arranged marriage to love marriage does not bring about the ability of young people in Asian countries to get involved in romantic relationships without their parents’ supervision. In other words, the freedom of mate choice in these countries does not lead to a ‘dating culture‘ similar to Western countries‘. The influence of parents and families on the individuals’ marriage is quite significant. Parents play an important role in the mate introduction and marriage decision- of a remarkable proportion of young people. Moreover, a considerable percentage of women rarely or never date with their husbands before marriage (Xiaohe & Whyte, 1990).

In the Vietnamese traditional society, marriage is viewed as one of three foremost turning points in men’s life (e.g. buying buffalos, getting marriage and building house) and an important event of the whole families and lineages (Mai Huy Bich, 1993; Tran Dinh Huou, 1989). Thus, parentally-arranged marriage is a common marriage pattern (Toan Anh, 1992: 73). Many men and women meet their spouse for the first time on their wedding days. In spite of families‘ remarkable influences, the transformation from arranged marriage to love marriage, as mentioned above, is evidenced in some research studies (Khuat Thu Hong, 1994; Le Ngoc Van, 2007; Nguyen Huu Minh, 1999). In parallel, the marriage process is strictly monitored by political - social organisations such as Youth Union or employers due to the impacts of the central planning economy and the collectivization of economic production (Belanger & Khuat Thu Hong, 1995). As a result, the concept of collectivism used in this paper includes not only families and lineages as the traditional approach does but also other organisations such as politico - social organisations or employers.

Applying this theoretical approach, this paper proposes a hypothesis that despite the increase in young people‘s freedom of marriage choice (including mate introduction, date and marriage decision) the influences of social groups, especially, families remain considerable.

3. Sample

This paper uses the quantitative and qualitative data of the survey titled ‘The Northern rural family in the 1976-1986 period’ conducted by the Institute for Family and Gender Studies in 2018 in Quynh Phu district, Thai Binh province (hereafter refers to as the 2018 survey). The quantitative sample of 410 respondents is people from 50 years old to 82 years old married in the 1976 – 1986 period. This sample is quite equally divided between husbands and wives and the two marriage cohorts including the 1976-1980 cohort and 1981-1986 cohort. The division of two cohorts represents the second and third five-year socio-economic development plans in Vietnam. The survey contains information on marriage and family including love and marriage, living arrangement after marriage, family structure, living conditions, socioeconomic and leisured activities, childrearing and siblings’ relationships during the first 5 years after marriage, in a special stage in Vietnam history - after the unification 1975 and before the Doi Moi 1986 (Renovation). In parallel, the survey involved 2 focus group discussions and 14 in-depth interviews which comprise of 6 interviews with men and women married from 1976 to 1980; 6 interviews with men and women marrying between 1981 - 1986 and 2 interviews with staffs of social organizations or local government officers at the time. Moreover, the quantitative data of the survey titled ‘The Northern rural family in the 1960-1975 period’ conducted by the Institute for Family and Gender Studies in 2017 in Quynh Phu district, Thai Binh province (hereafter refers to as the 2017 survey) is analyzed to clearly show the changing trend.

The representativeness of the survey sample is more likely to be affected by the following factors. The research sample is selected from individuals marrying between 1976-1986, currently living in the research site but not the total people married in this period in the ward because many of them would die or migrate to other places after marriage. An additional concern is that, due to surveying only the 1976-1986 married individuals, the research findings reflect the mate selection characteristics of married people but not the total population (including the single individuals).

4. Findings

4.1. Individuals‘ freedom in marriage process

Spousal searching

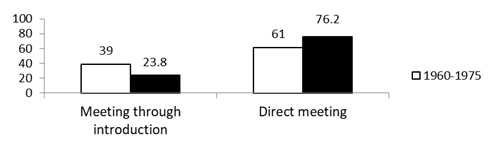

Analyzing the quantitative data of the 2018 survey shows that direct meeting steadily increases to become the major way in finding a spouse. The percentage of respondents finds their spouse in this way accounted for 76,1%. In comparison with the 2017 survey, this figure substantially went up by 15 percentage points. On the contrary, the proportion of respondents introduced to their spouse remarkably declined from 39% from 1960 to 1975 to 23,9% in the 1976-1986 period.

Figure 1. How to meet the spouses (%)

In spite of the increasing freedom in the spousal finding of people married from 1976 to 1986, the impact of collectives, especially parents, remains significant. In comparison with the period of 1960-1975, the percentage of respondents introduced to their spouse from 1976 to 1986 declined but accounted for around a quarter of total participants. Amongmatchmakers, parents and other family members played the crucial role with 75.3% meanwhile peers accounted for 14.4%. This result is similar to the common marriage pattern in some Asian countries such as China in the same period (Xiaohe & Whyte, 1990).

Individuals’ freedom in mate searching significantly changes over time. Compared to the 1976-1980 marriage cohort, the proportion of the 1981-1986 marriage cohort directly meeting their spouse increased by 10 percentage points (70.8% and 81.3%, respectively). This result confirms the increasing trend of active mate searching in this period. It seems that the implementation of the 1946 Constitution, the 1959 Constitution, the Law on Marriage and Family 1959 and then, the 1980 Constitution which states citizen’s freedom in love and marriage would partly change the traditional perspectives of individuals and families on marriage.

Gender has a substantial correlation with respondents’ active mate searching. Male participants are much more active than their female counterparts (82.7% compared to 70.1%). Searching a groom is traditionally less important than a bride, especially, for the eldest bride (Tran Dinh Huou, 1989), notwithstanding, women are more dependent on their parents and have less freedom in marriage than men.

Additionally, marrying someone who live in the same commune or ward has a strong correlation with individuals’ freedom in spousal searching. Compared to those living in different wards, the active mate searching rate for those living in the same commune was 30 percentage points higher and the figure for those living in the same ward was 17 percentage points higher. Despite the expansion of marriage radius and the significant looseness of the norm of marrying someone who lives in the same commune (Mai Van Hai, 2004), communes or wards are the key places in which individuals meet their spouse due to the limited transportation infrastructure, the migration restriction and the homogenous working environment in rural areas (e.g. 80% working in the agricultural sector). Moreover, a variety of collective activities in communes or wards such as regular meetings of political-social organizations, performance or sport activities, co-operative production activities or schooling create a favorable environment for individuals directly meeting their future spouse.

In brief, although family members, especially, parents play an important role in mate introduction the marriage pattern from 1976 to 1986 continues to increase individuals’ freedom in searching their spouse.

Marriage decision

Table 1 indicates that the marriages mainly arranged by parents and families are rare, conversely, the marriages in which respondents choosing their spouse either with or without their parents’ approval are dominant. Over 80% of respondents reported a marriage decision was made primarily by them. The freedom of individuals in marriage decision-also increases over time. Those making the marriage decision by their own (either with or without parents’ influence) increased from around 80% from 1960 to 1975 to approximately 90%in the 1976-1986 period. By contrast, the percentage of the marriage arranged by parents and families (either with or without respondents’ approval) reduced from around 20% to 10% in the same period.

Noticeably, among the marriages in which respondents completely made the decision by their own, a majority of those were accepted by parents (72%) while only 27% disagreed by parents and 4% of which parents had passed away. Our in-depth interview also indicates that in some cases parents initially disagree with respondents’ spousal choice but finally chose to be tolerant.

“At that time, my mom was not against my (marrriage) decision but she said that it is the right time for me to try to pass the university entrance exam, then, I should get married after graduation and having a stable job. Despite her advice, I was crazy in love at that time so that I decided to get married at all costs. Finally, she had to accept my choice” (In-depth interview with a male respondent married in 1984).

Table 1. Decision maker of the current marriage (%)

|

|

1960-1975

|

1976-1986

|

|

Arranged mainly by parents or family

|

6,0

|

4,4

|

|

Arranged by parents, with respondents’ approval

|

14,8

|

5,8

|

|

Respondents chose spouse, with parental approval

|

74,8

|

83,7

|

|

Respondents chose spouse, without parental influence

|

4,5

|

6,1

|

Between 1976 and 1986, the marriage decision-makers are significantly different among varied religions. The number of Christian followers choosing their spouse by themselves was much lower than those are non-religion or Buddhists (75.2% compared to 94.8%). Among individuals marrying between 1976-1986, the strictness of Christian law created barriers against their freedom in spousal choice.

In term of how individuals meet their spouse, people directly meeting their spouse are more independent in marriage decision making process than those meeting through an introduction (92% compared to 81.9%). At the same time, this result reflects the complication of individuals’ freedom in their marriage process from the first meeting to the marriage decision. Not all people directly meeting their spouse would certainly decide their marriage by themselves. A number of them marry the spouse chosen by their parents. Conversely, some individuals meet their spouse through parents or relatives but decide their marriage by themselves.

By comparison with individuals living in extended families, the proportion of respondents living in nuclear families choosing their spouse was 9 percentage points higher. Thus, the nuclear families provide opportunities for the prevalence of the love marriage, in contrast, the extended families maintain the traditional arranged marriage. This result is the same as the research study of Nguyen Huu Minh (2008) on the impacts of family size on marriage decisions.

It can be seen that the marriage pattern in the period of 1976-1986 continues to change from parentally-arranged marriage to love marriage. This transformation goes along with the transition from collectivism to individualism.

4.2. The stamp of collectivism in love and marriage before Doi Moi

Dating in the public eye

Although love and dating themselves is an exemplification of freedom in love and marriage, loving expressions of couples in the 1976-1986 period is limited and substantially influenced or controlled by families and communities. This clearly materialises in actual dating time, activities done together or the expression of emotions.

Even though the average time from the first meeting to a marriage of individuals marrying between 1976-1986 was not short (e.g. 13 months) the actual time that the couples spending together was limited.

“In our time, we had less time together. Besides working at the production unit in the daytime, we had no time together except for going to cinema or (he) coming to my house to chat with me under my parents’ watch. At that time, we did not dare to go out for chatting with each other because my mom did not allow. At that time, we wereso serious” (In-depth interview with a female respondent married in 1984).

In the same token, the activities which the couples can do together is rare. Although they work together in the same production units or participate in the same regular meetings or art performance practices of the Youth Union, they have fewer opportunities to express their love and care for each other. Sometimes, they don’t dare sitting next to each other to chat because “if we had sat next to each other, our friends would have teased us” (In-depth interview with a male respondent married in 1984). The couples are more likely to publicly do few activities together such as going to the cinema or pagoda but they need the approval of the girl’s parents.

“(At that time) If a movie was released, I had to go early to her house, sit in her dining room to have small talk with her parents, then, asked for her parents’ permission. I had to describe in detail our schedule on watching the movie, especially, the time to go back home. We had to go back to her home earlier or at least, at the exact time that her parents had allowed. Generally, we were so serious at that time” (FGD).

“During dating time, sometimes we went out together such as going to see the movie. If we wanted to go out together, I had to ask for my parents’ permission. If my parents agreed, he just dared to stand in front of my house gate to wait for taking me to go out. At that time, we had so limited leisure activities except for going to see the movie. Even when asking my parents for going to see the movie, I did not dare to say that I would go with him, I just said to go with my friends” (FGD).

In some cases, the male respondents would go to their girlfriend’s house in the evening but they have not much time to spend together because that date frequently occurs under the strict watch of the girl’s parents.

“Even close to the wedding day, we had rare times to ask for her parents’ permission to go out together. If having free time in the evening, I went to my girlfriend’s house, sat in the kitchen and chatted a few words with her, and then, asked her parents for leaving. We had less time to go out with each other” (FGD).

During the dating time, the couples have less directly love or care expressions for each other, even simple actions such as holding hands, especially, in the public sphere.

“I didn’t dare to hold her hand or sit next to her. When we sat in the kitchen, her parents, sometimes, dropped by to see whether we sit next to each other or not. We had to sit far from each other to chat” (FGD).

In some cases of loving from distance, the couples seem to feel free to show their love for each other through handwriting letters. They frequently write letters to each other. It seems that letters with its privacy and secret from the public help them to feel more confident to show their love and care.

“I wrote a letter to her weekly. I asked her about her health or other activities, and her parents, then, I told her about my work… Of course, I let her know that I miss her so much. Writing letters and sending via post offices became the only way to keep our contact because of the limited communication facilities at that time. I also promised the date to return home to celebrate our wedding ceremony” (In-depth interview with a male respondent married in 1977).

In general, the transformation from the traditional arranged marriage to the love marriage in the rural North of Vietnam before Doi Moi does not bring about a romantic sphere or “date culture” as in Western countries. The couples married between 1976-1986 have less time spent together, few activities doing together and less emotional expressions before marrying. This result similar to the general tendency in the Asian countries in this period (Xiaohe & Whyte, 1990).

This trend is attributed to some reasons. The strict monitoring from families and communities is one of the main causes for the couples’ fewer opportunities to publicly show their love to each other during the dating time. When discussing this issue, the common answers we got in either in-depth interviews or focus group discussions is “At that time, the public’s monitoring was so strict and serious but not as opened and free as now”. Individuals seem to have no private life including romantic relationships. They also have no private sphere to show their emotional expressions. Every activity of individuals including dating needs their parents’ permission and occurs in their parents’ or families’ watch. As a result, individuals rarely dare to publicly show their care or love to each other before marriage.

“To date a girl, we had to go to her house to ask for her parents’ permission. When her parents agreed, we dared to date and to go out with each other” (FGD).

In addition to families, the monitoring from political-social organizations such as Youth Union or the informal groups such as neighbors is an important factor impacting on individuals’ activities. Apparently, not only traditional norms but also modern cultural norms or lifestyles before Doi Moi aims to rigorously monitor an individual’s private life.

“When we were young, the rules were so strict that if we made a small mistake, we would be strictly criticized in the regular meetings of the Youth Unions or other meetings. They scrutinized even tiny mistake so that we had to strictly obey the rules” (FGD).

“We had to avoid a bad reputation or be rumored by neighbors that we love many people because this would negatively affect our family” (FGD).

Another important reason is the economic difficulties. Many households in Quynh Phu district, Thai Binh province still run out of food before the harvest time (Quynh Phu district Party Committee, 2009). Thus, it is a luxury for many young people to go out or go to the cinema together.

“My girlfriend and I each have seven siblings. At that time, we were so poor that we suffered from hunger due to running out of food. Thus, we had no money to go out together to fun places. For example, sometimes the movies were released in the ward but how we could earn the money to buy the ticket. We thought watching movies as a luxury” (In-depth interview with a male respondent married in 1976).

In brief, in spite of having quite a long time to date, the couples married between 1976-1986 in the rural North of Vietnam have few opportunities to represent their love and care for each other from spending actual time together, doing activities together and showing their emotional expressions. In other words, individuals seem to have no private sphere, no private life. An exemplification is that the romantic relationship – a fully private activity – occurs in the monitoring of many collectives from families to neighbours and political – social organisations. This indicates the strict control of both the traditional cultural norms (e.g. through families and neighbours) and the modern cultural norms (e.g. through political-social organisations) to individuals’ life.

Outsiders’ effect on marriage decision

Although the freedom of individuals in the spousal choice increased in the 1976-1986 period the influence of collectives including both parents or families and political-social organizations and employers on the marriage decision was significantly important.

Individuals deciding their marriage with their parents’ approval went up by 8.9 percentage points between the two periods of 1976-1986 and 1960-1975 while the difference in the percentage of respondents deciding their marriage without their parents’ influence was only 1.6 percentage points. This indicates that the increasing rate of respondents deciding on their marriage mostly occurs in those having their parents’ approval. This means that parents’ voice in individuals’ marriage decision is significant. More important, in some cases, the potential marriage would be failed due to parents’ disapproval.

“Before formal dating, men had to go to see women’s parents and asked for their permission. If they agreed, the couples started their formal dating. By contrast, if the parents disagreed, many couples had to stop dating because they did not dare to be against their parents’ decision” (FGD).

The prevalent marriage pattern in 1976-1986 is that individuals and parents choose the spouse together, and the marriage is proposed by the former. Individuals’ freedom or independence increases in parallel with parents’ significant influence on marriage decisions. This is seen as an effective way to raise the harmony and integration within family members (Nguyen Huu Minh, 1999). It is apparent that in spite of the transition to the love marriage and the individualistic tendency, marriage before Doi Moi is remarkably impacted by the traditional cultural norms (Vu Tuan Huy, 2004).

Filial piety is one of the key impact factors on marriage decisions in the period of 1976-1986. In Vietnamese traditional society, filial individuals were never opposed to their parents’ decisions. Both men and women never refused to get married to the spouse chosen by their parents (Toan Anh, 1992: 173). Although individuals’ freedom in marriage choice was officially regulated in the Law on Marriage and Family 1959 and then, the Constitution 1980, filial piety remains its remarkable impact on citizens’ viewpoint. For them, marrying the spouse selected by their parents is an “obligation”, a responsibility towards their parents and a way to reciprocate their parents’ unconditional love and care. “Mom and dad were so hard to bring me up so that I dare not to against my parents’ spousal choice” (FGD).

“In sum, marriage is an obligation. I had to do my marriage obligation as my parents’ expectation, then, I had to have two children. My parents forced me to get married, and then, had two children in the first four to five years. When visiting home for one month in 1977, I was introduced to my spouse by my parents. During this month, my family organized the engagement ceremony for me. After that, I came back to my office. To be honest, I understand nothing about my wife because we knew each other in a very short time. I got married to just fulfill my responsibility to my parents. I did not want to oppose to my parents” (In-depth interview with a male respondent married in 1979).

Filial piety in general and care responsibility towards parents when getting old in particular is so strong in the eldest sons. Our qualitative data shows that some respondents who are the eldest son decide to break up with their current girlfriend and return their hometown to get an arranged marriage in order to take care of their parents and families.

“When participating in the military, I had a girlfriend in the South but I decided to break up with her to return my hometown because of my family. I have only one brother but he stayed at Da Nang province so that I had to return home. I did not like to go back home but I had to do that to take care of my parents. They did not force me to go home but it is my responsibility to my parents” (In-depth interview with a male respondent married in 1978).

Even though the freedom in the spousal choice increases and individuals become more independence from their parents they tend to be monitored by many organizations such as their working offices or Youth Unions. 90.1% of respondents had to report on their marriage decision to their organizations to get approval. This result is the same as the research finding of Mai Van Hai and Ngo Ngoc Thang (2003) on the role of organizations such as Youth Unions in the marriage process. The role of the local authority and political-social organizations is so important that the absence of them in the wedding ceremony would lead to feel that the marriage is unaccepted and cause the worry to not only brides and grooms but also their families and lineages.

Generally, the stamp of collectives, especially parents, is remarkably important. Clearly, marriage in the rural North of Vietnam in the period of 1976-1986 is still seen as the event of the collectives, particularly for the whole families instead of individuals. The power of the traditional marriage norms partly remains in this period in parallel with the influence of modern institutions such as working office or political-social organizations. In other words, in tandem with the increasing impact of individualistic tendency, collectivism significantly remains its effects in the marriage pattern in this period.

5. Discussion

To conclude, the transition from the arranged marriage to the love marriage in the rural North of Vietnam before Doi Moi 1986 is quite complicated. The traditional marriage pattern is transforming into a more modern pattern while the influences of collectives, especially, families remarkably remain. It can be said that, thereby, the marriage pattern in this period is combined traditional features with modern characteristics, the individualistic tendency with the collective trend even though the former seems to be in favor of. This result contributes more evidence for Triandis’s perspective (1995) that collectivism and individualism are able to parallel exist if having an appropriate combination. It is an effective way to maintain the harmony in the families and to adapt with the particular context of Vietnam before Doi Moi.

The prevalence of the love marriage pattern in the rural North of Vietnam goes along with individuals’ increasing freedom and independence during the marriage process. Individuals directly meeting their spouse outnumber those through the introduction by parents or peers. Individuals choosing their spouse significantly go up over time. This increasing freedom of individuals in the marriage process also reflects the development of the individualistic tendency. This finding is similar to previous research studies in Vietnam (Nguyen Huu Minh, 1999; Nguyen Huu Minh, 2008; Vu Tuan Huy, 2004) as well as the general trend in other Asian countries in the same stage (Dion & Dion, 1993; Xiaohe & Whyte, 1990).

Similar to other Asian countries (Xiaohe & Whyte, 1990), in the transition to the love marriage in the rural North of Vietnam before Doi Moi, the marriage pattern is still remarkably affected by parents and families. A number of children meeting their spouse through introduced by parents or relatives. The prevalent marriage pattern in this period is individuals’ marriage decisions with their parents’ approval. The involvement of both individuals and parents in the marriage decision represents that marriage in the rural families is still the event of the whole families or lineages although the position of individuals and parents is changed, even reversed.

The impact of non-traditional collectives such as employers or political-social organizations on the marriage process is a new feature of marriage before Doi Moi compared to the Vietnamese traditional society. The strict monitoring of these groups, in parallel with families, limits the private sphere of the young people in rural areas. They seem to have no private sphere, no private life under thecontrol of both the traditional and modern cultural norms. This is one of characteristics of marriage in Vietnam society on the way to develop the centrally planned economy.

_______________________________________________

Endnote

* Nguyen Ha Dong, MA, Institute for Family and Gender Studies.

([1]) When mentioning the change of marriage pattern, the concept of collective does not refer to general social groups or institutions but family, relatives and tribe.

References

Belanger, Daniele & Khuat Thu Hong. (1995). "Some Changes in Marriage and Family in Ha Noi from 1965 to 1992." Sociological Review (4):27-41.

Buunk, Abraham P., Park, Justin H., & Duncan, Lesley A. (2010). "Cultural Variation in Parental Influence on Mate Choice." Cross-Cultural Research 44(1):23-40.

Dang Phong. (2013). "Breach the Barriers" in the Economy in the Night before Doi Moi, Ha Noi: Knowledge Publishing House.

Dion, Karen K. & Dion, Kenneth L. (1993). "Individualistic and Collectivistic Perspectives on Gender and the Cultural Context of Love and Intimacy." Journal of Social Issues 49(3):53-69.

Goode, William. (1963). World Revolution and Family Patterns, New York, London: Free-Press of Glencoe, Collier-Macmillan.

Hui, C. Harry & Triandis, Harry. (1986). "Individualism-Collectivism: A Study of Cross-Cultural Researchers." Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 17:225-248.

Kerkvliet, Benedict. (2000). "Relationship between Villages and the State in Vietnam: Impacts of Daily Political Life on the Eradication of Old-styled Collectivization." 301-334 in Some Issues in Agriculture, Farmers and Rural Areas in some Countries and Vietnam, edited by Kerkvliet, B., Scott, J., Nguyen Ngoc, & Do Duc Thinh. Ha Noi: The Gioi Publisher.

Khuat Thu Hong. (1994). "Formation of Rural Families in the New Socio-Economic Context." Sociological Review (2):76-84.

Le Ngoc Van. (2007). "Dating and Marriage Decision in the Rural Vietnam in Doi Moi." Sociological Review (3):24-36.

Le Ngoc Van. (2011). "Dating and marriage Decision in Rural Vietnam." 80-101 in Rural Families in Doi Moi Vietnam, edited by Trinh Duy Luan, Rydstrom, H., & Burgoorn, W. Ha Noi: Social Sciences Publishing House.

Le Ngoc Van. (2012). Family and Family Changes in Vietnam, Ha Noi: Social Science Publishing House.

Mai Huy Bich. (1993). Main Characterstics of Families in the Red River Delta, Ha Noi: Culture and Information Publishing House.

Mai Van Hai. (2004). "Investigating the Culture of Viet Villages in the Red River Delta through the Change of Marriage Radius over a Half of the Century." Sociological Review (4):51-60.

Medora, Nilufer P. (2003). "Mate Selection in Contemporary India: Love Marriages Versus Arranged Marriages." 209-230 in Mate Selection Across Cultures, edited by Hamon, R. R. & Ingoldsby, B. B. Thousand Oaks: Sage Pulications Inc.

Nguyen Huu Minh. (1999). "Freedom in Mate Choice in the Red River Delta: Tradition and Change." Sociological Review (1):28-39.

Nguyen Huu Minh. (2008). "Mate Selection Pattern in Vietnam: Tradition and Change." in Proceedings of the international conference on 3rd Vietnam Studies.

Phan Dai Doan. (2001). Villages and Wards in Vietnam: Some Economic-Cultural-Social Issues Ha Noi: National Political Publishing Hous.

Toan Anh. (1992). Traditional Norms of Vietnamese People, Ho Chi Minh city: Ho Chi Minh City Publishing House.

Tran Dinh Huou. (1989). "Vietnamese Traditional Families with the Influence of Confucianism." Sociological Review 2:25-38.

Triandis, Harry. (1995). Individualism and Collectivism: Westview Press.

Triandis, Harry & Gelfand, Michele. (2012). "A theory of individualism and collectivism." 498-520 in Handbook of theories of social psychology: volume 2, edited by Lange, P. A., . M., Kruglandki, A. W., & Higgins, E. T. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Vu Tuan Huy. (1995). "Several Dimensions of Family Changes." Sociological Review (4):13-26.

Vu Tuan Huy. (2004). "Marriage and Family." 65-86 in Trends in Current Family (Some Main Findings from a Empirical Research in Hai Duong Province), edited by Vũ Tuấn Huy. Ha Noi: Social Science Publishing House.

Xia, Yan R. & Zhou, Zhi G. (2003). "The Transition of Courtship, Mate Selection, and Marriage in China." 231-246 in Mate Selection Across Cultures, edited by Hamon & Ingoldsby. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.

Xiaohe, Xu & Whyte, Martin King. (1990). "Love Matches and Arranged Marriages: A Chinese Replication." Journal of Marriage and the Family 52(3):709-722.

Sources cited: Vietnam Journal of Family and Gender Studies. Vol. 14, No. 2, p. 30-4, 2020