Abstract: This paper aims at analysing Vietnam’s current shortage of skilled labour and assesses the causes of this shortage. Some of the reasons include insufficient training with an educational approach, the lack of technology infrastructure, low investments in research and development (R&D) due to a mismatch between supply and demand. Finally, the paper gives some recommendations for policy implementations and solutions to improve Vietnam’s skilled labour market. These solutions focus on the training and education system, vocational training and on strengthening partnerships between firms and universities, and attracting highly skilled Vietnamese labour forces from abroad to return home.

Keywords: Vietnam, labour, skilled labour shortage.

Subject classification: Economics

1. Introduction

In early 2012, Vietnam’s Government identified three bottlenecks in the economy that must be resolved immediately to guarantee sustainable growth and development: infrastructure, institutional framework and human resources, of which skilled labour is the most important part. Even more important than capital are human resources as a key factor for economic development. However, for developing countries, like Vietnam, it is challenging to acquire a skilled labour force. The country has not yet a skilled labour force with the desired composition and quality. The main reasons for this are the lack of proper education and training as well as utilisation mechanisms to motivate a skilled labour force to lead the economy in the right direction, towards competitiveness and efficiency. The small size of the skilled labour force, coupled with inefficient utilisation, has weakened the economy’s competitiveness. The establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (2015) will transform the ASEAN into a region with free movement not only of goods, services, and investments but also of skilled labour and capital. Therefore, this is an opportunity for Vietnam to counter the shortage of skilled labour and focus on solutions to train skilled workers for the future.

2. Current situation of skilled labour in Vietnam

Skilled labour is defined as any labour with special skills, training, knowledge, and abilities in their field. Skilled labourers may have attended a college, university, or technical school, and can be either blue-collar or white-collar workers, with varying levels of training or education [13].

As a part of human resources, skill labourers currently hold management, professional, or technician positions. Highly skilled labour is generally characterised by advanced education (college and higher), the possession of knowledge and skills to perform complicated tasks, as well as the ability to adapt quickly to technological changes, and a creative application of knowledge and skills acquired through training in their field [1].

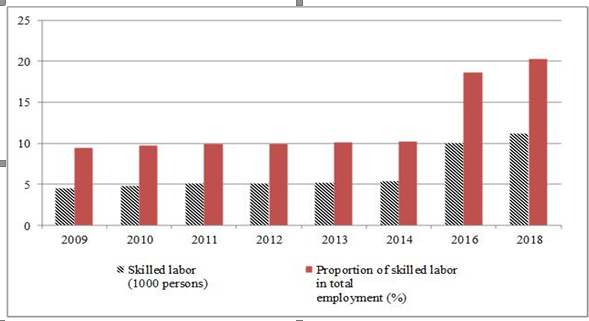

Vietnam has achieved rapid economic growth since the renovation (đổi mới) in the 1990s and has taken advantage of increasing foreign direct investment (FDI). Despite the rapid development, the amount of skilled labour is still small compared to the demand of the industrialisation, modernisation and international integration process. From 2009 to 2014, the skilled workforce grew annually by an average of only 175,000 persons, equivalent to only 1/5 of the increase in the total number of jobs. Skilled labour is mostly concentrated in the areas of education and training (30% of the skilled labour force), activities of State administration and National Security and Defense (19%), and social work (8%). The shortage of skilled labour is one reason preventing foreign firms from expanding production in Vietnam. According to the Ministry of Information and Communications in 2017, Vietnam needs about 1.2 million people in the information technology sector by 2020, with a shortage of over 500,000 people. These shortages lead to delays, loss of investment opportunities, less R&D, slower innovation, and fewer trade opportunities. The country is currently lacking 78,000 IT workers a year, and the figure would rise to 100,000 a year by 2020. The number of IT jobs increases by 47% a year, but that of IT workers only grows by 8% [6]. Moreover, only about 30% of the candidates can meet the recruiters’ requirements. Enterprises need skilled labour in IT and e-commerce because businesses focus on social networking and e-commerce platforms to perform highly efficient.

In 2014, Vietnam had nearly 5.4 million skilled labourers. Now the skilled labour force makes up only 10.2% of the total number of jobs nationwide. A relatively rapid increase in the number of skilled labourers happened between 2009 and 2017, from 4.5 to 5.4 million workers.

In 2018, the Vietnamese workforce over the age of 15 amounted of about 54 million, but only 11.00 million people (20,3%) were skilled workers, meaning unskilled workers made up 80% of the country’s total workforce [12]. The lack of skilled labour is likely to slow down the country’s desired economic transition from being reliant on labour-intensive industries to producing high-tech goods, which in turn could reduce Vietnam’s competitiveness. The shortage of skilled labour leads to lower labour productivity than that of other countries in the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC).

Vietnam ranks 87th amongst 119 countries in terms of their ability to attract, develop, and retain talent [2]. Currently, around 40% of FDI firms in Vietnam find it difficult to recruit skilled workers. The lack of skilled labour has become an increasingly obvious barrier to growth in value-added exports such as high-tech goods. This lack is also a deterrent for foreign companies looking to invest in high-tech manufacturing.

Table 1: Size of Skilled Labour in Vietnam

Source: General Statistics Office, Labour Force Surveys of 2009-2014 and General Department of Statistics Vietnam; Bích Thủy (2018), "Manpower Group Helps Vietnam Develop Skilled Workforce for Industry 4.0", Vietnam Investment Review.

Vietnam had 27.8 million skilled technicians, accounting for 51.6% of the total labour force. However, there were only 10.9 million graduates from primary to postgraduate, accounting for slightly more than 20%. In 2017, the rate of workers with technical expertise - college-level or higher - accounted for more than 17% [10]. The demand for skilled labour has been increasing in Vietnam due to the following three trends:

Firstly, Vietnam is now a middle-income country able to compete internationally based on possessing a highly-skilled workforce. Tasks requiring high skills have become more important.

Secondly, the Industrial Revolution 4.0 has already replaced many low-skilled repetitive roles with automation and robotics. Multinational companies (MNCs) now need the cleverest employees to compete and succeed globally. High-skilled occupations have expanded most rapidly, while mid-skilled occupations have declined.

Thirdly, FDI firms are in dire need of highly-qualified human resources, especially after the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) took effect in Vietnam (14 Jan 2019). More firms are choosing Vietnam to relocate their production bases in China to avoid the US-China trade war.

In Vietnam, the shortage of necessary skilled workers is much more serious than in other ASEAN countries like Singapore,

Malaysia, and Thailand. Vietnam’s productivity was low, just one-fifteenth of Singapore, one-fifth of Malaysia and two-fifths of Thailand, being grouped in the four bottom ASEAN countries for its low capital, scientific, technological, and labour levels [11].

The shortage of engineers and managers can be seen in most sectors, such as tourism and export. The tourist industry requires 40,000 workers, but the number of graduates from tourism schools is estimated at just around 15,000, of whom graduates from universities and colleges account for only 12%. Over the next five years (2018-2023), Vietnam’s tourism workforce needs to grow by 20% annually to meet the rising demand. The lack of more skilled labour has become an increasingly obvious barrier to growth in value-added exports such as high-tech goods and keeps local firms from going global.

Vietnam is far behind China, Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand in the field of skilled workers while developing a highly skilled workforce is critical to attracting FDI into value-added industries. Vietnam’s shortage of skilled workers hinders FDI and is one reason preventing South Korean (Republic of Korea) firms from expanding production in Vietnam. Korean companies want to purchase more modern machines to expand production in Vietnam but are concerned about the difficulty in finding qualified engineers to run them.

Industry 4.0 has led to a conversion trend in different areas of the human resources market, especially in technology and manufacturing. As a result, there are also higher demands for new occupations in the job market, such as data analysis, engineering, and automation. At this rate, Vietnam has been behind the employers’ demand for new quality roles. It is estimated that in 2020, Vietnam will need approximately 13.6% skilled workers out of the total number of jobs, which means doubling the current size (an increase by more than 4.3 million persons in absolute terms), or an average annual increase by 400-500 thousand persons (11-12% per year).

3. Causes of skilled labour shortage

Shortages in Vietnam’s skilled labour force can have many causes. These include:

Firstly, insufficient training and education as well as a vocational training system that fails to meet the skill requirements of the industry. A key reason for Vietnam’s lack of high-skilled workers lies in its educational system, which traditionally focuses on memorising theory rather than acquiring practical skills. The quality of such training is not high and is not well-oriented in selecting a career. As Vietnam wants to attract more foreign investors, an education reform is necessary.

Skills shortages have been a persistent problem due to inadequate higher education and training. Skills development has not kept pace with economic growth and the demand for skilled workers. Rising demand for skilled workers is especially expected in the garment industry, tourism, hospitality services, and information and communications technologies. Improving the education system to develop the appropriate sets of skills will be imperative to address current and anticipated shortages.

According to the 2018 World Economic Forum (WEF), despite great efforts to reform vocational training, Vietnam still ranks 87th among 90 surveyed countries in training capability and skilled labour attraction. Vocational schools set enrolment plans based on demand from parents and students, not on demand or needs of the society and economy. Only 10% of high school graduates choose vocational training, but the labour market needs more skilled workers. The number of university graduates is very large, but their capabilities cannot meet firms' requirements. Poor training programmes are also a cause of the low quality of school graduates. While the market changes regularly, the training curricula remain about the same.

Moreover, it is difficult to adapt the technical skills learnt within the vocational training system to real work environments. Students expressed an interest in having greater opportunities to gain technical expertise through hands-on learning rather than through classroom sessions focusing on theoretical issues. The quality of the training that students received was limited, with schools placing greater focus on generalised courses and less emphasis on the specialised skills and practice with machines. Additionally, due to limited capital, vocational schools often cannot buy equipment for lessons. Therefore, State-owned vocational schools cannot fulfil the role of providing high-quality workers to the market. A leading cause for this is the fact that state-owned schools do not have the pressure of competition and cannot enjoy autonomy in their decisions.

Secondly, there is a lack of technology infrastructure. The demand for skilled labour is going to continue to grow as technology keeps advancing in the future. Vietnam might face a serious shortage of skilled labour in information technology (IT) in the coming years, with about half a million IT professionals less than needed by 2020. The country’s capability of absorbing technologies is low, which makes it difficult for them to cooperate with foreign enterprises when opportunities arise. While 80% of foreign investment enterprises in Vietnam use medium level technology, 14% use outdated tech, and only 5-6% use hi-tech.

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), approximately 86% of textile and footwear industry workers in Vietnam are at risk of losing their jobs due to technology. Vietnam ranked 90th in technology and innovation and 70th in human capital, among 100 countries [3]. Vietnam’s infrastructure is improperly linked as a result of poor planning and has difficulties in attracting funding, especially from non-state sources.

Many Vietnamese private companies are using technology that is about 50 years out of date. As a consequence, Vietnam is far behind its competitors in the region. Small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for up to 98% of all non-state firms in Vietnam, and most of them are still using technology from the 1960s and 1970s. Due to the lack of funding, private firms, especially SMEs, cannot afford sufficient investment in technology. Many of these enterprises are spending only 0.2-0.3% of revenue on updating technologies, compared with 5% in India and 10% in South Korea. Only 20% of Vietnam's enterprises have applied hi-tech in their business, compared with 73% in Singapore, 51% in Malaysia, and 31% in Thailand. As a result, Vietnam ranked 102nd out of 148 economies in the world.

Thirdly, R&D spending is comparably low. Expenditure on R&D is a key indicator of government and private sector efforts to obtain competitive advantages in science and technology. Vietnamese enterprises are weak at R&D activities, with 80% of enterprises having no R&D facilities. According to the Ministry of Science and Technology (MST), Vietnam spends much less on R&D than other countries. The number of researchers and technicians in Vietnam is also too low. In 2011, Vietnam’s gross domestic expenditure on research and development (GERD) was VND 5.293 trillion or USD 0.25 billion. This means that the ratio of the expenditure on GDP was 0.21%.

Meanwhile, the GERD index of the US was 2.77% in 2011, or 13 times higher than Vietnam’s. The total sum of money the US spent on R&D activities was USD 450 billion, or 1,785 times higher than Vietnam’s [9]. China also spends much more money than Vietnam on R&D activities. Chinese GERD was 1.84% in 2011, or 8.7 times higher than that of Vietnam. China spent USD 250 billion on R&D or 1,000 times more than Vietnam.

Fourthly, due to mismatches between supply and demand. “Skill shortages” refer to the situation when the supply is less than the demand for the skilled labour market. After AEC establishment, skilled workers can move freely in the open ASEAN labour market, which creates chances for Vietnam to attract those employees.

Skill shortages are of concern for employers, not least because they are associated with productivity shortfalls. The main indicator of skill shortage is the fact that employers cannot fill vacancies for skilled workers.

Vietnam’s demand for highly-skilled workers will continue to grow steadily in the wake of increasing foreign investment inflow, causing a severe supply shortage of highly-qualified human resources in the market. In the field of information and technology, many Vietnamese and foreign firms wish to set up software development centres, but they cannot find enough engineers to meet their demand because of the supply shortage.

Additionally, the supply of skilled tourism workers also falls short. The severe shortage of qualified workers is a huge challenge to the rapidly growing tourism sector. The sector is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 7% between 2016 and 2020, and as a result, the total demand for direct human resources is expected to be a whopping 870,000 by 2020. The sector’s demand for human resources will be two or three times the number needed by other major sectors such as education, health, and finance. However, demand for training far outstrips the supply from training institutions.

4. Solutions for the skilled labour shortage

Vietnam considers human resources a golden key to its future success, and improving the quality of Vietnam’s skilled workforce should become the most crucial factor in competition and growth. The remarkable talent shortage will get even worse in 2020 if Vietnam’s leaders do not take effectual action. So, the development of a skilled workforce will be one of the top priorities. The solutions to develop highly qualified human resources to support sustainable development are as follows:

Firstly, improving training and education systems as well as labour quality in the direction of standardisation and modernisation, particularly renovating vocational training. The demand for skilled workers in the context of Industry 4.0 requires timely innovation by the higher education system. Therefore, improving Vietnam’s education system and training of highly skilled workers should be the top priority. Teaching and training will make workers more dynamic and creative. The Government has taken steps to increase vocational and technical training in order to meet the requirements of the labour market. In March 2018, the Vietnamese Government introduced Decree No.49/2018/ND-CP that provides for the accreditation of vocational education. Vietnam also encourages foreign firms to invest in training centres to develop their human resources sustainably. Since 2017, Vietnam has topped ASEAN countries in expenditure on education by spending 5.7% of its GDP on teaching and learning activities. The Government needs to increase investments in training and education to build a skilled workforce. In 2018, the Government provided vocational training to 2.2 million people.

Renovating the education and training system to be more dynamic and flexible is a vital requirement to overcome the skill gaps as well as to adapt rapidly to the demands of the labour market. The Government will focus on investing in its training system. The first focus is the training of new workers with technical expertise. The second focus is to provide retraining and advanced training for labourers who are already working. Retraining and advanced training will be conducted in three forms: in professional education institutions, at schools, and in classes of business enterprises.

Secondly, strengthened partnerships between firms, universities, vocational schools, and cooperation with international organisations can further help to develop skilled human resources.

Education in Vietnam is currently not linked to training and demand. The educational and training infrastructures provided by both Government and industry are insufficient to prepare employees to take full advantage of economic integration. So, the vocational schools should cooperate with enterprises in training in order to give students opportunities to work with machines at enterprises. However, only private vocational schools are aware of the importance of cooperation with enterprises.

Businesses and firms should cooperate with schools and colleges to produce more skilled workers. Accordingly, schools can focus on training on businesses' real requirements. Businesses should not only forecast their labour demand and make orders with education establishments but also participate in building education curricula and teaching.

In order to have high-quality workers, companies need to have periodic training programmes and improve the quality of training by strengthening co-operation among businesses, universities, and associations. Businesses also need to consider setting up human resource development funds as well as cooperation with other companies in training and recruitment because most of the Vietnamese firms are still financially weak.

In 2018, Manpower Group - a world leader in innovative workforce solutions, signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA) to support Vietnam in developing a skilled workforce and effective regulatory frameworks for the digital age.

Thirdly, attracting highly skilled migrant workers and creating an environment with positions for such workers. Vietnam is already part of a flow of talent across the region.

As an emerging economy, Vietnam will also benefit from an influx of skilled, knowledgeable workers from around the world. Challenges migrant labourers are currently facing include lack of protection, high recruitment costs at recruitment centres, costly and lengthy migration procedures, migration quotas and domestic employment policies that prevent them from easily changing their jobs. Therefore, policies need to focus on strengthening migrant labourer’s protections while lowering barriers to their mobility. Vietnam gains 7% of GDP from remittances, so it should follow the strategy to protect their migrants overseas.

More attention should be paid to improving the quality of the working environment and more incentives should be offered to employees to encourage them to take more responsibilities in their work; therefore, creating an environment to nurture and appreciate talents, and reform fundamental policies of attracting and treating skilled workers, as well as developing specific policies to attract talents and Vietnamese students abroad to come back and serve the country. In 2018, about 90,000 Vietnamese highly-skilled workers in a variety of sectors such as machinery, construction, and food processing were on their way back home.

Besides attracting foreign experts and high qualified labour to come to work in Vietnam, the country needs to build teams of leading specialists in key areas associated with the country’s industrialisation strategies.

Fourthly, truly embrace science and technology as the top national policy. Science and technology should be considered a national policy, a direct production force, but many policies, in general, have not considered science and technology as the most important motivation and key factor for Vietnam to escape the middle-income trap for rapid and sustainable development. Since 2000, the percentage of State budget spent on S&T activities has roughly matched the required number of 2% of the total State budget (including expenditure for S&T in national safety and security). The average expenditure for S&T accounts for 1.46% of the total budget spent (~0.4% GDP) in the 2011-2016. Expenditure for R&D accounts for 40% of the total budget spent on S&T. There should be policies to encourage the private sector to join science and technology activities by allocating funds smoothly and transparently for enterprises and individuals. When the tax and financial mechanisms are strong enough, the enterprises will be the centre of the national innovation system so they can focus on investment in science and technology as well as human resource training. Another goal should be to increase the proportion of spending on building national science and technology capacities, with particular priorities for information and communication technology. Science and technology products of enterprises should be supported to penetrate the domestic and international markets. Vietnam has had many national product development programmes, technological innovations, but there is no policy to encourage and support of Vietnamese enterprises’ products to reach the domestic and world markets.

Fifthly, supply and demand for skilled labour should be linked to labour market management. To successfully link skills to productivity, employment creation and development, skills development policies should target three objectives: matching supply to the current demand for skills, helping workers and enterprises adjust to change, anticipating and delivering new and different skills that will be needed in the future.

Vietnam has abundant labour resources, but many enterprises in the country cannot recruit a sufficient number of skilled workers, and as a result, cannot expand production activities due to mismatches between the level of skills and demand from employers because of a shortage of quality candidates. So, the Government should enhance public-private partnerships and carry out projects related to the labour market as well as regularly provide analyses and forecasts of market trends and develop more policies to help enterprises improve their human resources. On the other hand, companies should provide information about their demands for schools to improve the quality and effectiveness of their training. Universities, colleges, and vocational schools should update training programmes towards enterprises’ real demands.

Vietnam is in a golden population period with hundreds of thousands of university and college graduates each year, in addition to millions of workers participating in the labour market who need vocational training. Meanwhile, the labour market is being internationalised and more competitive, requiring Vietnam to develop an organised labour market with higher quality workers.

5. Conclusion

In 2018, skilled workers shortage was a major challenge, with only 41% of manufacturers being able to find skilled workers. Particularly, effective leadership skills are more critical in the manufacturing industry than ever before. The demand for skilled workers is increasing and is not being met for a variety of reasons. This shortage will likely persist or even get worse and makes training a necessity for any business wishing to stay competitive. However, skilled labour is a socio-economic phenomenon, and thus is not simply a matter of economics. Therefore, any effective skills-gap solution requires substantial investments of time, money or even both. There is a need for synchronised solutions, both nationally and multi-nationally, to ensure highly-skilled labour is used efficiently for both society and the employees themselves.

________________________________________

(*)Institute of Chinese Studies, Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences.

References

[1] Viện Khoa học Lao động và Xã hội (2013), Chương trình khoa học công nghệ cấp nhà nước, mã số: KX.01/11-15, Giải pháp thúc đẩy chất lượng lao động có kỹ năng để đáp ứng nhu cầu tăng trưởng kinh tế hướng đến công nghiệp hóa, hiện đại hóa, Hà Nội. [Institute of Labour Science and Social Affairs (2013), State-level Key Science & Technology Programme, KX.01/11-15, Solutions to Improve Quality of Skilled Labour Force to Meet Needs of Economic Growth towards Industrialisation and Modernisation, Hanoi].

[2] Bruno Lanvin and Felipe Monteiro (2019), The Global Talent Competitiveness Index (GTCI): Entrepreneurial Talent and Global Competitiveness, INSEAD, Fontainebleau, France.

[3] The World Economic Forum’s System Initiative on Shaping the Future of Production (2018), The Readiness for the Future of Production Report 2018.

[4] Policy Brief (2014), Skilled Labour: A Determining Factor for Sustainable Growth of the Nation, Policy Briefly, Institute of Labour Science and Social Affairs (ILSSA) and International Labour Organisation (ILO), Vol. 1, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/--- asia/---ro-bangkok/---ilo-hanoi/documents/ publication/wcms_428969.pdf, retrieved on 30 June 2014.

[5] General Statistics Office, Labour Force Surveys of 2009-2014 and General Department of Statistics Vietnam, https://www.dezshira.com/library/ infographic/skilled-workers-in-vietnam-by-level-of-education-2016-6658.html, retrieved on 20 December 2016.

[6] Anh Kiệt (2018), Vietnam Faces Severe Shortage of IT Manpower, Science and Technology, http://www.hanoitimes.vn/ science- tech/2018/03/81e0c382/vietnam-faces-severe-shortage-of-it-manpower/, retrieved on 21 March 2018.

[7] Klaus Schwab (2018), The Global Competitiveness Report 2018, World Economic Forum (WEF), http://www3.weforum.org/ docs/GCR2018/05FullReport/TheGlobalComp etitivenessReport2018.pdf, retrieved on 1 December 2018.

[8] Bích Thủy (2018), “Manpower Group Helps Vietnam Develop Skilled Workforce for Industry 4.0”, Vietnam Investment Review, https://www.vir.com.vn/manpowergroup-helps-vietnam-develop-skilled-workforce-for-industry-40-60320.html, retrieved on 21 June 2018.

[9] Le Van (2014), How much does Vietnam Spend on R&D? https://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/ science-it/109017/how-much-does-vietnam-spend-on-r-d-.html, retrieved on 6 August 2014.

[10] Vietnam News (2018), Vietnam Needs to Improve Training of Highly Skilled Workers, https://vietnamnews.vn/society/480827/viet-nam-needs-to-improve-training-of-highly-skilled-workers.html#EDpLiq31oWomI9Ax. 97, retrieved on 27 November 2018.

[11] Vietnam Law and Legal Forum (2016), AEC Poses Tough Challenges for Vietnam Labour Market, http://vietnamlawmagazine.vn/aec-poses-tough-challenges-for-vietnam-labor-market-5207.html, retrieved on 2 February 2016.

[12] Vietnamnet (2019), Foreign Firms in Vietnam Face Skilled Workforce Shortage amid FDI Wave, https://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/business/217044/ foreign-firms-in-vietnam-face-skilled-workforce-shortage-amid-fdi-wave.html, retrieved on 30 January 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skilled_worker, retrieved on 23 April 2019.

Sources cited: JOURNAL OF VIETNAM academy OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, No. 4 (192) - 2019