PHAM HUY THONG*

Abstract: Catholicism is one of the largest religions in the world, but the history of the Catholic Church in Vietnam is not as long as other religions. It has experienced ups and downs during the periods of its introduction, dissemination and proliferation due to various factors, including differences with the local culture. Over time, however, the impacts of Vietnamese culture and the inventiveness of the Vietnamese people brought Catholicism closer to local people and it became imbued with Vietnamese cultural identity. Various characteristics of the Catholic Church in Vietnam with respect to language, music, painting, architecture, arts, literature, liturgies and rituals contain features of Vietnamese cultural identity such as the patriotic tradition, openness and social cohesion of the agricultural community. On the other hand, the Catholic Church has also contributed to the enrichment of Vietnamese culture for the people.

Keywords: Catholic Church, impact, identity, culture, Vietnam.

Subject classification: Religious studies

1. Introduction

Catholicism is an international religion. Nowadays, the Catholic Church is prevalent all over the world. No matter where is it practiced, even in those countries with their own dominant religions such as Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Orthodox Church, etc., it is easy to see the similarities of the Catholic Church with respect to the organisational structure, rituals, the Bible, architecture of church buildings, paintings, statues, and an absolute compliance with the Pope. The Catholic Church in Vietnam certainly shares these features as well. However, it includes elements particular to Vietnamese culture, such as the patriotic tradition, openness, and the social cohesion of the agricultural community, which have been developed over time by the Vietnamese people. The paper, therefore, focuses on analysing the features of Vietnamese culture and identity as reflected in the Catholic Church in Vietnam.

2. Vietnamese identity shown in Catholic Church in Vietnam

The Catholic Church traditionally originated in the Middle East, and then it vigorously spread to Europe. When the Catholic Church was introduced into Vietnam, it brought with it characteristics of Western culture and civilisation. It played a role as a bridge for cultural exchange between Vietnam and the rest of the world. Catholic priests contributed greatly to the Roma-nisation of the Vietnamese written language, making it more accessible. The Catholic Church in Vietnam also provided the country with many famous cultural figures such as Nguyen Truong To, Han Mac Tu, and Truong Vinh Ky, etc., as well as promoting a healthier lifestyle such as monogamy and stable marriage. In turn, Vietnamese culture has contributed to enriching the religion, turning Catholicism from an unfamiliar religion into one close to the Vietnamese people. Firstly, liturgies were translated into Vietnamese. Originally they were only in Latin. That is why the following line of verse was penned: “Preachers are reading the Bible in Latin, while girls are softly singing hymns” (Vietnamese: Các thày đọc tiếng Latinh/ Các cô con gái thưa kinh dịu dàng). Soon afterwards, however, proper names were converted into Vietnamese for the purpose of making it easier for Vietnamese people to pronounce and understand; for example, Deus was called “Đức Chúa Trời” (i.e. God); and, Dominico, Benedicto, and Vincente were called “Đa Minh” (i.e. Saint Dominic), “Biển Đức” (i.e. Pope Benedict), and “Vinh Sơn” (Saint Vincent) respectively. In regard to names, in the early days, once a Vietnamese person joined the Catholic Church, he/she would take a Christian name such as Maria, Anna, Andrew, Dominic etc., like those Christians in the West. As an example, the title of demigod was bestowed upon a parishioner in Phu Yen, but people did not know his real name and just called him “Chân phước Anrê Phú Yên” (i.e. Blessed Andrew of Phu Yen). Later, names of foreign missionaries were converted to Vietnamese names in order for them to integrate more easily with Vietnamese communities. For example, Alexandre de Rhodes was known as “Đắc Lộ”; Bishop Pierre Joseph Georges Pigneau de Béhaine was named “Bá Đa Lộc”; while Father Léopold Cadière was named “Cố Cả”. In regard to linguistics, many idioms reflecting characteristics of local areas were widely shared among Catholics. For example, the idiom “Cha Phú Nhai, khoai chợ Chùa” (lit. Father of Phu Nhai, sweet potatoes of Chua market) in the Diocese of Bui Chu means that delicious sweet potatoes were found abundantly in Chua market (Nam Truc District, Nam Dinh Province). Many Catholic priests were born in Phu Nhai village (Xuan Truong District, Nam Dinh Province), in fact more than 100 priests and four bishops. Meanwhile, the idiom “Quan làng Vụ, cụ làng Báng” (lit. Mandarins of Vu village, priests of Bang village) was well-known by many people in the Archdiocese of Hanoi. It means that over many periods, Vu Ban was the home village of many government officials, while Xuan Bang was the home village of many Catholic priests. In the Diocese of Phat Diem, the idiom “Kinh cụ Thể, lễ cụ Sâm, mâm cụ Sáu, cháu cụ Thịnh” (lit. preaches/tenets by Priest The, ceremonies by Priest Sam, trays of Priest Sau, grandchildren of Priest Thinh) mentions particular characteristics related to the Catholic priests in the diocese: Father The took the examination of matrimonial tenets very strictly; Father Sam took a long time to complete a ceremony; Father Sau’s (Tran Luc’s) copper tray used to carry offerings was as big as a broad flat drying basket; Father Thinh had a large flock - which means he had a lot of parishioners.

Initially, some Vietnamese Catholics translated the Bible into Vietnamese in the form of verse making it easier to disseminate among people. As written by Alexandre de Rhodes, “The most outstanding and also the first person among those, who have been baptised and have received faith, is the older sister of the [Trinh] Lord. She is very good at Chinese characters and poetry. We call her Catarina2 (…) Lady Catarina has a passion for knowledge and always ponders the mysteries of faith; being very good at poetry, she has composed verses about the entire history of Catholic dogmas, including the creation of the world, the nativity of Jesus, life with sufferings, the resurrection and the ascension of Jesus Christ” [5, p.206].

Unfortunately, 3,000 lines of verse “in the local language with a melodious voice” have all been lost. At present, we can find 8,000 sentences in verse from “A song of prophecy” (Vietnamese: Sấm truyền ca) and “A Section of Bible” (Vietnamese: Tao đoạn kinh), etc., written by Priest Lu Y Doan (in the period from 1683 to 1687), who was born in Quang Ngai Province. His poems were written in Nôm script, skilfully reciting the history of Catholicism and its viewpoint in a way appropriate for the Vietnamese culture. “Loài người từ thủa A-đam/ Đua nhau xây dựng, nảy ham làm trời/ Một pho Kinh thánh ra đời/ Thiên niên vạn đại những lời do Thiên…/ Cơ trời sinh hóa, hóa sinh/ Ngũ hành thiên địa, tiến trình ngàn năm” (i.e. Since the time of Adam, mankind tried its best to build life/ A Bible was created/ Which contains everlasting sayings from God/In Heaven’s scheme, things are born and changing constantly…/ The creation of the universe is a process of thousands of years).

Due to the demand for making the Vietnamese language convenient for propagation, some foreign missionaries collaborated with Vietnamese people to Romanise it, thereby creating a modern writing system for the Vietnamese language called the “Chữ Quốc ngữ” (lit. national language script). A number of patriots such as those at the Tonkin Free School (Vietnamese: Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục) realised that the national script was a really good way to broaden the population’s knowledge and consciousness: “Recently, a Portuguese priest created a national language script, using 20 letters of the European language in combination with six accent marks and 11 digraphs to spell our language simply and quickly. As citizens in the country, we should learn the national language script to record things in the past and present. We can also write letters to one another. Gradually, we can refine our text to express our ideas well. It is really an initial step to broaden our wisdom” [10].

For the same reasons, priests in Japan, Korea, and China also wanted to Romanise the scripts of their national languages, but failed to do so. One of the reasons for the success in Vietnam is that Vietnamese people, with a culture of great tolerance, decided to adopt the Romanised script when they realised the advantages it brought. Vietnamese cultural identity is also shown in rituals and liturgies of the Catholic Church in Vietnam. Liturgies consist of various activities of the Catholic Church, including the Mass, praying, singing hymns, choir recitals and ceremonies as well as other performances. The first point to mention relates to the Catholic holy books. The Bible was translated very early into the Vietnamese language as well as into languages of other ethnic minorities such as Ba Na, Stieng, and Mong, or H’Mong, etc. At present, the Catholic Church still continues to hold classes for people of ethnic minorities. In order to work in ethnic minority areas, it is obligatory for Catholic nuns and priests to be able to read and write the languages of that particular ethnic minority.

The second point is that traditional dress was immediately accepted by Catholic priests, both foreign and local ones. The image of a Catholic priest dressed in a traditional Vietnamese male áo dài and sporting a turban, like a Confucian scholar in the past, was a very familiar sight for everyone. Father Martini wrote, as follows, about the attendance of Father Superior at Lord Trinh Trang’s death anniversary held by Lord Trinh Tac on 29 December 1650: “Respecting the local custom and following the traditional rituals of Vietnam, Father Superior came in bare feet, wearing a black gown and a black hexagonal turban. He bowed down to the ground according to the Vietnamese way. Thus, Lord Trinh felt very satisfied and ordered to start the music as if Lord Trinh just completed praying. Everyone was surprised and thought that an important title had just been bestowed upon the Father” [12, p.324]. In comparison, we can mention the Chinese Rites Controversy, an argument that took place among members of the Catholic Church lasting more than a century (from the 17th to the 18th centuries) and across the reigns of ten Popes. The controversy caused severe damage to the Catholic Church, as it was one of the reasons Catholicism was prohibited in Japan, Korea, China, and Vietnam.

After the decree Plane compertum est issued on 8 December 1939, the Holy See started to allow Catholics in oriental countries to observe their ancestral rites. In Vietnam, however, owing to the open-mindedness of the priests of the Society of Jesus and the enthusiastic collaboration of Vietnamese people, ancestral worship was accepted much earlier than the acceptance proclaimed by the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965). As Alexandre de Rhodes explained in his first doctrinal talk, each person has three subjects for adoration: the parents, who gave birth to him/her, the king, who rules over the country, and Father in the Heaven. The adoration of parents is a completely honourable activity.

“As we all have parents, this body was born… We owe our parents a debt of gratitude for the pregnancy lasting for nine months and ten days, the labour pains, and the breastfeeding and mouthfeeding for three years. Mothers sometimes starve themselves to save food for children. They eat unsavory pieces of food so as to give the delicious ones to children. Mothers sometimes have to lie in uncomfortable wet places to provide comfortable and dry places for children. After giving birth to children, they feed and bring them up.

Fathers have to get up early to go out and do various jobs, in order to earn money to feed their children. It is correct that children have to show filial duty and respect to their parents” [6, p.18].

Similarly, before passing away, Bishop Pierre Joseph Georges Pigneau de Béhaine also showed his support for ancestral worship among Vietnamese Catholics, although it was forbidden by the Vatican Council. After the announcement of the acceptance was promulgated on 14 June 1965, the Vietnamese Catholic Church [7, pp.142-144] lifted the restriction on ancestral worship. Consequently, Vietnamese Catholics were allowed to thurify before the picture of the dead as a particular feature of the Catholic Church in Vietnam. The Catholic Church has enriched Vietnamese culture in the field of literature and arts, and similarly Catholic literature and arts has featured elements of Vietnamese culture. When Catholicism was disseminated into Vietnam, local people did not have Western produce such as olive leaves to make offerings on Palm Sunday so they used coconut palm tree leaves instead. On Tet holidays, when preparing the Lunar New Year pole (Vietnamese: cây nêu), they braided it into the shape of the Cross. Holy Communion was celebrated in a similar way to village festivals. Groups of men played castanets, beat drums, and played clarinets. Women wore the four-panel traditional dress (Vietnamese: áo tứ thân) and conical hats made of palm leaves, while men wore gowns and hexagonal turbans. The saint’s palanquin was painted in gold and red lacquer. Inside the church, worshippers were separated on both sides in accordance with the oriental custom: men on the left and women on the right. However, there was a difference in the form of a group of trumpeters and a choir singing modern music in harmony.

In addition, with regards to folklore and language, Vietnamese Catholics created a treasure trove of idioms and folk songs about the weather, harvests, and festivals. For example:

- Lễ Ba Vua (6-1), chết cua, chết cá (On the Feast of the Epiphany, it is so hot that crabs and fish will die).

- Lễ Rosa (7- 10) thì tra hạt bí (On the Rose of Lima feast day, it is the time to sow squash seeds).

- Lễ Các Thánh (1-11) thì đánh bí ra (On All Saints Day, it is the time to replant the squash seedlings).

- Lễ Các Thánh (1-11) gánh mạ đi gieo (On All Saints Day, it is the time to sow the sprouted rice seeds).

- Lễ Sinh nhật (25-12) giật mạ đi cấy (At Christmas time, it is the time to transplant the rice seedlings).

- Tháng giêng ăn Tết ở nhà (the first lunar month is the time to enjoy the Tet holiday at home).

- Tháng hai ngắm đứng, tháng ba ra Mùa (the second lunar month is the time to enjoy a view, and the third is the time to harvest rice).

- Tháng tư tập trống, rước hoa (the fourth lunar month is the time to practise playing the drums and carrying flowers).

- Kết đèn, làm Tạm, chầu giờ tháng năm (making lanterns, rehearsing and waiting for the fifth lunar month).

- Tháng sáu kiệu ảnh Lái Tim (the sixth lunar month is the time to hold the procession of the picture of Jesus Christ).

- Tháng bảy chung tiền đi lễ Phú Nhai (the seventh lunar month is the time to spend money attending the festival at the Basilica of Phu Nhai).

- Tháng tám đọc ngắm Mân Côi (the eighth lunar month is the time to read and pray the Holy Rosary).

- Trở về tháng chín, xem nơi chồng mồ (the ninth lunar month is the time to visit the graves).

- Tháng mười mua giấy sao tua (the tenth lunar month is the time to buy coloured paper to make stars).

- Quay qua một, chạp sang mùa ăn chay (when the eleventh and twelfth months of the lunar year arrive, let's be ready to welcome Lent).

In regard to music, Vietnamese Catholics initially sung hymns in Latin. By the 1920s, Father Vuong (Nam Dinh Province) and Father Doan Quang Dat (1877-1956, Hue city) started translating them into Vietnamese. In August 1945, the Le Bao Tinh choir was formed with the following objective: “Regarding the content, it serves Jesus Christ and the Nation; regarding the artistic performance, folk songs from all the three regions of the country will be used as the main structure of tones” [7, p.160]. As a result, hymns consisted of folk melodies such as love duets (Vietnamese: Quan họ) from Bac Ninh Province, Cheo traditional opera (Vietnamese: hát chèo) from northern provinces, Then (Vietnamese: hát then) from the Tay and Nung ethnic minority groups, and the cheerful tunes of the Central Highlands etc. Many songs in Vietnamese were very popular, including “Winter’s Night” (Đêm đông) composed by Hai Linh and the Vietnamese version of “Prayer of Saint Francis” (Kinh Hòa bình) by Kim Long… In respect to paintings, originally the Catholic Church introduced many classic works of world famous painters such as Raphael’s “The Sistine Madonna” and “The Last Supper” by Leonardo da Vinci etc., to the Vietnamese people. Vietnamese painters would wonder why Catholic paintings only depicted images of Western people, while the Vietnamese also had an image of Jesus Christ in mind. And so Catholic works of art depicting local landscapes and people were painted, such as “The Birth of Jesus” (Giáng sinh) by Nguyen Gia Tri, “Magdalene at the Foot of the Cross” (Madalena dưới chân Thập giá) by Le Van De, “Virgin Mary of Vietnam” (Đức Mẹ Việt Nam) by Nam Phong, and a number of paintings of the Virgin Mary depicted by Nguyen Thi Tam. Looking at the painting “Virgin Mary of Vietnam”, we can recognise it is the image of a Vietnamese queen, based on her traditional dress and the way she lulls a child to sleep, although the map of Vietnam is absent. Similarly, when it comes to architecture, during the early missionary period, churches in Vietnam were built either in the Gothic architectural style with pointed bell towers or square-topped ones in the Roman style, which were very popular in the West at that time. By the late 19th century, however, church buildings reflecting oriental architecture appeared in Vietnam. Typically, in the Diocese of Phat Diem, we not only see local materials such as wood and stone used to build the Cathedral, but also features of a communal house roof and the three-entrance village gate are apparent. In addition, a bell hanging in the bell tower of the gate is struck with a vồ, or mallet, a wooden tool used in the old days in Vietnam and still seen in the countryside today, with a handle and large head. "Vồ" can be used for striking items such as bells or in agriculture for beating piles of earth breaking up the soil to create a good environment for the seeds. Recently, many churches built in the styles of ethnic minorities have sprung up in Vietnam. For example, the architecture of Lang Son church is similar to that of the eight-roof long houses of the Tay and Nung ethnic minorities. The Pleichuet church roof in Gia Lai Province is 35m high, similar to that of the communal house of the Ba Na people. In many local areas, church buildings have been designed following the oriental philosophy belief of the harmonious integration of nature, society, and human beings. As a result, man-made rock gardens, lakes, and decorations depicting peach blossoms, daisy flowers, Phyllostachys, and Ochna integerrima trees are found in church environs.

Similar to the number of Chinese characters in each line of antithetical couplets, a church building has an odd number of compartments, or bays, such as five, seven or nine. In addition, it is easy to recognise the Vietnamese spirit in Bible texts read at church such as the Chinese version of Litany of Loreto, Praise Her with a Flower, and Lamentation of Christ, etc.

Based on the Vietnamese tradition of tolerance, Vietnamese Catholics show a friendly attitude towards other religions. In the early days, as a monotheistic religion, Catholics did not accept the existence of any other faiths. All other religions were considered to be flawed. Due to the Vietnamese people’s amiability, as shown in the proverbs: “Bên cha cũng kính, bên mẹ cũng vái” (i.e. Run with the hare and hunt with the hound; lit. respecting the father’s side, and/when also bowing to the mother’s side, implying respecting both [seemingly different] sides) and “Có thờ có thiêng, có kiêng có lành” (i.e. Pray for holiness, Abstain for good; lit. If you worship, things are sacred, implying: you will receive auspicious things bestowed on you; If you abstain, you will be free of bad things/you will get good things), the exclusion of other religions was not set in stone. Although ancestral worship was forbidden at that time, some Catholics kept the ancestral altar in a hidden room. Some of them still secretly visited pagodas to burn incense and pray on the first and the fifteenth days of the lunar month. People loved and provided mutual help for others without questioning if they followed the Catholic faith, even when local authorities imposed a draconian treatment on the Catholic Church or other religions. The concept of “xôi đỗ” villages (xôi = steamed glutinous rice, đỗ = beans, a dish containing two ingredients, implying a village made up of people following different religions) was widely accepted by Vietnamese people, demonstrating that those of different faiths can live in harmony with one another. This was mentioned in some village conventions, for example, the convention of La Tinh village (Hoai Duc District, Hanoi) in 1896, as follows: “In our village, because Catholics and non-Catholics have different customs, we have to hold this meeting to rationally discuss our village-based tasks and duties. A new convention will be made to regulate custom-related activities and land allocation for the Christian God or Buddha worship, with which all people in the village will have to comply. Both Catholics and non-Catholics have to consider the duties relating to taxes, dyke maintenance, labour contribution, and soldiers’ wages as common tasks that we all have to undertake. People can be distinguished between Catholics and non-Catholics, but we all are living in the same village and some of us come from the same lineage and we, therefore, should treat each other reasonably and friendly” [3, p.109].

In Vietnam, therefore, people following different religions could marry each other. It was no longer an unfulfilled desire. King Bao Dai married Nguyen Huu Thi Lan, a Catholic girl, in 1934, more than three decades before the acceptance by the Second Vatican Council. The following beautiful line of verse was published to show the marriage commitment: “Because you love me, I will keep saying “amen” without paying attention to whether you will burn the incense making the ancestral worship” (Vietnamese: Quý hồ chàng có lòng thương/ Amen mặc thiếp khói hương mặc chàng). After the acceptance was officially promulgated by the Second Vatican Council, Catholics started to regard people of other religions as friends. As a result, the relationships between Vietnamese Catholics and non-Catholics became more and more amicable.

Another important characteristic of the Catholic Church in Vietnam is that Catholics always associated themselves with those involved in national affairs. This tradition was the result of efforts made by millions of Vietnamese people.

Catholicism was introduced into Vietnam when the country was colonised by the West. At that time, many Catholics took part in patriotic activities, as they considered themselves firstly Vietnamese and secondly Catholic. One such individual was Nguyen Truong To (1830-1871). He was persistent in his submission of 58 reports to the royal court of the Nguyen dynasty, suggesting how to make the people wealthy and the nation powerful enough to defeat, and drive away, the French invaders. It demonstrates that he put the national interest above that of religion. He was the first person to use the concept of “accompanying/being the companion of [the nation]”: “Catholic people are born and brought up by the Creator, and religions are also fostered by the Creator; moreover, Catholics are part of the people in the country. Of those people, perhaps some are betrayers, but they just account for a thousandth or a hundredth at most… In any religion, if someone is a betrayer, he or she will be considered guilty and consequently must be punished, in order to make the religions purer. For others, who comply with the law, they should be let [practicing the religion] as it does not cause any harm. It is fine that people are companions, provided that they are not opposed to one another” [1, p.118].

Some Catholics directly rose up in arms against the French colonialists, such as Doi Vu in Nam Dinh and Lanh Phien in Quang Binh Provinces. Others joined the patriotic movements led by Phan Boi Chau and Phan Chau Trinh. The following extract is from a report submitted by Élie Jean-Henri Groleau, Resident Superior of Annam (Central Vietnam), to the Governor of Indochina on 11 February 1911: “Leaders of the movements have attracted the participation of many Catholic priests and preachers in the region of Nghe Tinh… Thus, based on the intermediary role played by the priests and preachers, they have exerted a widespread political influence on Catholic people in the region. As a result, a campaign against us has been launched effectively among Catholics. And, they have also contributed quite a large amount of money to Cuong De’s camp3” [7, p.285].

Many Catholic priests and followers were imprisoned by the French authorities. Some priests such as Dau Quang Linh and Nguyen Thanh Dong were exiled to Con Dao Island. Some died in prison, for example, Father Nguyen Van Tuong from the Diocese of West Dang Trong (Vietnamese: Tây Đàng Trong), present-day Diocese of Vinh.

When the August Revolution took place in 1945, 200 Catholic postulants participated in the 2 September 1945 parade. Painter Le Van De, who was Catholic, was responsible for designing and decorating the rostrum in Ba Dinh square, on which President Ho Chi Minh read the Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

Composer Dinh Ngoc Lien, who conducted the brass band in playing “the Marching Song” (Vietnamese: Tiến quân ca), the national anthem of Vietnam, was also a Catholic. Catholics in dioceses all over the country joyfully welcomed national independence. At that time, Vietnamese Catholic bishops sent wires to the Vatican, the United Kingdom, the United States and Catholics around the world, calling for support of the Viet Minh government and the independence of Vietnam. During the “Gold Week” when donations to the new government were made, Bishop Ho Ngoc Can of the Diocese of Bui Chu even contributed his pectoral cross, while Queen Nam Phuong donated all her pieces of jewelery to the fund of the revolutionary government. Many Catholics belonged to agencies of the government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Some of them held important positions. For example, Bishop Le Huu Tu and Bishop Ho Ngoc Can were government advisors, Father Pham Ba Truc held a position equal to the present-day Vice Chairman of the National Assembly (Vietnam's Parliament), Mr Nguyen Manh Ha was the Minister of the National Economy, Mr Ngo Tu Ha and Dr Vu Dinh Tung held ministerial-level positions at the Ministry of War Invalids and Veterans and the Ministry of Health, etc. After the national reunification in 1975, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Vietnam issued a Pastoral Letter in 1980, which demonstrated national pride as a cultural feature. It was the first time the Catholic Church in Vietnam had, in its documents, unprecedentedly made such strong appeal: “Love of the nation and the compatriots is not only a natural feeling, but also required by the Gospel… Our patriotism must be practical; i.e. we have to be aware of existing issues of the country, understanding the State’s policies and, together with the people within the whole country, contributing to the protection and development of a Vietnam of wealth, freedom, and happiness” [4, p.244].

Continuing with the spirit of the 1980 Pastoral Letter, during the period of renovation and international integration, the seven million Vietnamese Catholics continued to make every effort to build the country, hand in hand with the rest of the population.

Adept in both religious and secular occupations, they took part in patriotic activities, especially charity work. Many nuns were recognised in society as out-standing examples of people who devoted themselves to the field of care work such as leprosy camps, medical centres for HIV carriers, and running “classes of mercy/ love” for deprived children. For example, in 2006 Mai Thi Mau (Di Linh District, Lam Dong Province) was honoured as “a heroine during the period of renovation”. Catholics in Vietnam have contributed trillions of VND to campaigns for education, safeguarding Vietnam’s sovereignty over its seas and islands, and projects to build new-style rural areas etc. Many Catholics have been given honourable titles such as Professors cum People’s Teachers Luong Tan Thanh and Vu Van Chuyen; composers Nguyen Xuan Khoat and Luong Ngoc Trac; and writers and poets Nguyen Hong, Bang Ba Lan, Ho Dzenh, and The Lu. The international integration process and the market economy have resulted in Vietnam having achieved a great deal in terms of socio-economic development. However, at the same time, social evils have become more severe, especially drug addiction, which ruins both the happiness of many families and the future of countless young people. In such a situation, Cardinal Pham Dinh Tung, Archbishop of Hanoi, once made an appeal in a pastoral letter, as follows: “I am making this urgent call to share with all people in preventing and eradicating completely this social evil from our families and villages. I am requesting fathers to preach about the harm caused by the evil so that people can be fully aware of it. In each diocese, a plan must be made to investigate and seek out drug addicts. Parents should regularly keep a close watch on their children, preventing them from going to places where they potentially have contact with drug addicts and get involved in drug addiction.

For those, who have got addicted by mistake, we should give advice to them with humanity and help them by all means to detoxify completely as soon as possible; if not, the addiction will be spread from them to others like an oil slick” [9, pp.85-86].

Consequently, some members of the Catholic community were involved in the fight against drug addiction. In the past, Phuc Tan parish (Hoan Kiem district, Hanoi) was a hotbed of drug addiction in the city, but by 2010 the number of addicts in the parish had dropped down to three and they tried to detox at home with the community’s support.

Also regarding the lifestyle, Vietnamese bishops criticised the literal interpretation of the phrase “each day brings its own bread”, advising Catholics to take responsibility for bringing up their children, as stated in the 1992 Pastoral Letter:

“At present, human beings are found abundantly everywhere on earth. It is, therefore, necessary to think about how to feed and educate young generations of humankind. The order to reproduce more to fill the earth is closely attached to the order to take control over the earth. Thus, once we give birth to a child, we have to feed and bring up the child so that he/she will become a good person. This requires us to deal with an existing urgent and serious issue, which is to be responsible for reproduction and educating the children”.

In regard to the economic aspect, in the past Vietnamese people used to look down on those who traded. At the time, tradespeople were referred to derogatorily as “con buôn” (huckster), since they were ranked the lowest in social hierarchy, i.e.: “[Confucian] Scholars - Farmers - Craftsmen - Traders”. On the other hand, in the past, some Vietnamese Catholics had understood the following sentence from the Bible too literally: “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter Paradise”. They were, therefore, afraid of getting rich. When priests arrived in Vietnam to preach the Catholic faith, they advised and taught the local people how to earn money by “buying things at a cheap price, and selling at a higher price” and how to lend money with reasonable interests: “It is probably good for lenders to use money to buy rice fields. Buy rice, when its price is low, and sell it when its price is high. If you are not good at doing trade, you should cooperate with someone else in doing it. You may invest money, while the other invests time and energy. If a profit is gained, it will be shared by both of you. If there is a loss, it will mean that you have lost some money, while the other has lost time and energy” [11, pp.150-151]. Having the cultural tradition of adopting new values, Vietnamese Catholics changed their mindset and followed the advice given.

Following the advice of Catholic priests, many traditional craft villages were revived by Hanoi’s Catholic community, such as the palm-leaf conical hat making village of Vac (Ung Hoa District), Bat Trang ceramic village (Gia Lam District), Tay Tuu flower village (Bac Tu Liem District), and Phu Thuong bonsai village etc. In 2010, the highest yearly income of a Catholic household in Hanoi was VND 500 million, but by 2019 many Catholic households were earning much higher incomes, amounting to one or two billion VND. Some Catholics received a certificate of merit from the Chairman of Hanoi People’s Committee in recognition of their successful household economic development. In many areas, Catholics took advantage of international ties to boost economic development. In the Diocese of Thanh Da (Quynh Thanh commune, Quynh Luu District, Nghe An Province), all the 11,330 local residents are Catholic. During the period from 1995 to now, the annual funds spent on infrastructure is roughly VND 3 billion, of which 30% was contributed by the local people, 31.6% was allocated from the State budget, 13.2% from the local budget, and the remaining 26.2% was donated by Vietnamese Catholic priests living in Switzerland, who originally came from the commune. In 1995, a secondary school was built in the commune, costing VND 647 million, of which VND 468 million was donated by Priest Tran Minh Cong. In 2004, a clean water plant was built in the commune, costing VND 5.4 billion, of which VND 1 billion was paid for by local Catholic people and priests. In the Diocese of Thanh Duc (Da Nang city), the construction of a church cost VND 2.612 billion. The local people in the diocese contributed VND 400 million with the balance coming from overseas Vietnamese. The above-mentioned development of craft villages and economic activities was seen as a way to make the Catholic Church in Vietnam adopt traditional cultural values. In addition, it is also necessary to mention the Catholic contribution to the country’s moral values and lifestyles. In the modern society, the divorce rate is rapidly increasing. According to data from the Supreme People’s Court, from 1977 to 1982, there was an average of 5,672 divorces in Vietnam a year. In 1991, the corresponding figure rose to 22,049. In 1994 and 1995, it increased to 34,376 and 35,684 respectively. Meanwhile, in Hai Van commune (Hai Hau District, Nam Dinh Province), home to 6,000 Catholics, the number of divorces was just two over an 18-year period (from 1982 to 2000). In the Diocese of Ha Hoi (Thuong Tin District, Hanoi), where 1,500 Catholic people lived, only two couples separated during the entire period from 1945 up to now [7, p.82]. Clearly, the Catholic Church has been helping people live healthy lives and maintain happy family units. When families are stable and happy, social order and security will be better, as the number of children negatively affected by their parents’ divorce will reduce. When the COVID-19 pandemic started spreading all over the world, including Vietnam, Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc issued Instruction No.16/CT on the measure of social distancing to prevent the spread. All Catholic dioceses issued pastoral letters, instructing Catholic communities to temporarily stop holding ritual ceremonies in public. Instead, they should hold them online via the internet. Given Holy Week liturgies and Easter were in early April this year 2020, Catholics complied well with the social distancing instructions. In a pastoral letter of Xuan Loc Episcopal See, the following advice was given: “Everyone has to learn how to live silently, spending more time reading the Bible, looking at the inner mind to sincerely realise one’s short-comings and weaknesses in order to pray for compassion from God. Parents and grandparents should remind their children and grandchildren to attend online rites and recite the rosary more often. Treat one another with compassion; please know how to apologise, sympathise, forgive, and be more generous. In all circumstances, Catholic families should care about spiritual and material difficulties of neighbouring families, including non-Catholics and migrants. With the compassion of God, please care for and share with them” [2].

Based on the instructions from Catholic priests, many charitable activities have been carried out all over the country. Caritas Archdiocese of Ho Chi Minh City provided free meals twice a day worth VND 100,000 for those without jobs and hence unable to earn a living, such as lottery-sellers and street hawkers until social distancing was lifted. A Catholic businessman in Phan Rang city (Binh Thuan Province) opened a food store providing meals and rice for poor people at a cost of VND 2,000 per a meal and VND 1,000 per two kilogrammes of rice. He applied a simple pricing structure to ensure the poor people did not feel self-pity. They would have a sense of having bought their meals and rice themselves rather than begging for them. Many Catholic people contributed money and rice to relief funds during the pandemic period. In Thach Ha (Ha Tinh Province), dozens of Catholic households, such as those of Nguyen Trung Hau, Nguyen Thi Phap, and Nguyen Hong Phong, donated from 1 to 1.5 tonnes of rice and VND tens of millions. The Diocese of Thai Ha (Hanoi) provided 3,000 free packages each containing 10 kilogrammes of rice and a mask for poor people.

Son Loi commune (Vinh Phuc Province) was placed under lockdown when it reported a cluster outbreak of COVID-19. Of the 10,000 residents, 1,300 were Catholic. To make people feel reassured, the Diocese of Bac Ninh sent a young priest, who had studied medical sciences, to the commune with protective equipment to carry out pastoral care.

3. Conclusion

Since Catholicism was introduced into Vietnam, it has contributed to the enrichment of Vietnamese culture. Similarly, Vietnamese culture and Vietnamese Catholics with their patriotic spirit and creative minds have enriched the religion and turned it from an unfamiliar one into a religion closely aligned to, and imbued with, Vietnamese cultural identity.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Photo 1: Phat Diem Cathedral

Source: Author.

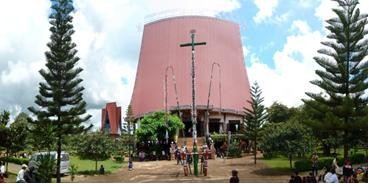

Photo 2: Pleichuet Church Built in Architecture of Communal House of Ba Na Ethnic Minority People in Gia Lai Province

Source: Author.

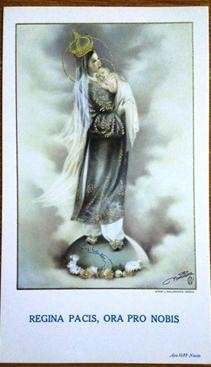

Photo 3: Nam Phong’s Painting “Virgin Mary of Vietnam”

Source: Author.

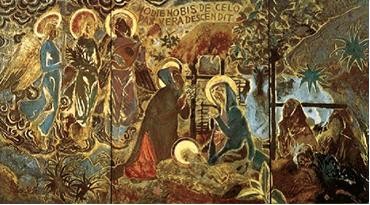

Photo 4: Nguyen Gia Tri’s Lacquer Painting “The Birth of Jesus”

Source: Author.

Notes

* Institute of Viet Mind.

1 The paper was published in Vietnamese in: Nghiên cứu Tôn giáo, số 4, 2019. Translated by Nguyen Tuan Sinh, edited by Stella Ciorra.

2 The Vietnamese name for St Catherine.

3 A Vietnamese prince who went to Japan to ask for help to fight the French.

References

[1] Trương Bá Cần (1988), Nguyễn Trường Tộ - con người và di thảo, Nxb Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, Tp. Hồ Chí Minh. [Truong Ba Can (1988), Nguyen Truong To: Life and Works, Ho Chi Minh City Publishing House, Ho Chi Minh City].

[2] Đinh Đức Đạo (2020), Tâm thư của Giám mục Đinh Đức Đạo, Tòa Giám mục Xuân Lộc ngày 10 tháng 4 năm 2020. [Dinh Duc Dao (2020), Letter of Bishop Dinh Duc Tao, Xuan Loc Archdiocese, 10 April 2020].

[3] Kỷ yếu Tọa đàm khoa học Một số vấn đề văn hóa Công giáo từ khởi thủy đến đầu thế kỷ XX, Huế, tháng 10 năm 2004. [Proceedings of the Conference “Some Issues on Catholic Culture from Initial Period to Early 20th Century”, Hue city, October 2004].

[4] Niên giám Giáo hội Công giáo (2005), Thư chung năm 1980, năm 2001, Nxb Tôn giáo. [Yearbook of Catholic Church in Vietnam (2005), Pastoral Letters of 1980 and 2001, Religions Publishing House].

[5] Alexandre de Rhodes (1994), Lịch sử Vương quốc Đàng Ngoài, Tủ sách Đại kết, Ủy ban Đoàn kết Công giáo Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, Tp. Hồ Chí Minh. [Alexandre de Rhodes (1994), History of the Kingdom of Tonkin, Dai Ket Books, Ho Chi Minh City Committee for Catholic Solidarity, Ho Chi Minh City].

[6] Alexandre de Rhodes (1998), Phép giảng tám ngày, Tủ sách Đại kết, Ủy ban Đoàn kết Công giáo Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, Tp. Hồ Chí Minh. [Alexandre de Rhodes (1998), Cathechism for Those Who Want to Receive Baptism, Dai Ket Books, Ho Chi Minh City Committee for Catholic Solidarity, Ho Chi Minh City].

[7] Phạm Huy Thông (2004), Ảnh hưởng qua lại giữa Công giáo và văn hóa Việt Nam, Nxb Tôn giáo, Hà Nội. [Pham Huy Thong (2004), Interactions between Catholic Church and Vietnamese Culture, Religions Publishing House, Hanoi].

[8] Phạm Huy Thông (2005), Nửa thế kỷ người Công giáo Việt Nam đồng hành cùng dân tộc, Nxb Tôn giáo, Hà Nội. [Pham Huy Thong (2005), Half a Century of Vietnamese Catholics Accompanying Nation, Religions Publishing House, Hanoi].

[9] Phạm Đình Tụng (2000), Những chặng đường mục vụ tại Tổng giáo phận Hà Nội (1994-1999), Hà Nội. [Pham Dinh Tung (2000), Service Periods in Hanoi Archdiocese (1994-1999), Hanoi].

[10] Văn tuyển văn học Việt Nam 1858-1930, Nxb Giáo dục 1989. [Selected Vietnamese Literary Works during Period from 1858 to 1930, Education Publishing House, 1989]. Nguyễn Khắc Xuyên (1994), Lịch sử địa phận Hà Nội, Paris. [Nguyen Khac Xuyen (1994), History of Hanoi Area, Paris]. Marini P. de (1966), Histoire Nouvelle et Curieuse des Royaumes de Tunquin et de Lao, Gervais Clouzier Publisher, Paris.

Sources cited: JOURNAL OF VIETNAM academy OF SOCIAL SCIENCES No. 4 (198) - 2020