Luong Thi Hong*

Abstract: After World War II, the world was formed into two different systems: capitalism and socialism, leading to a new form of war - "Cold War". Although being called "Cold War," it was manifested by "Hot Wars" such as those in Indochina and the Korean peninsula. The Korean War (1950-1953) and the Vietnam War (1954-1975) were convergence points of confrontation between the two systems. While both of the wars were partly an East-West conflict, they were also a "North-South" conflict. This paper examines a reference by comparing the Korean War and the Vietnam War from a perspective of the Cold War system. Due to developing differently in the international, regional, and national contexts, the Korean War and the Vietnam War differed in various dimensions. The article proposes the similarities and dissimilarities between the two wars and how they still influence present historical issues.

Keywords: Korean War, Vietnam War, Cold War.

Subject classification: History

1. Introduction

The Second World War ended in 1945 leading to establishing a new world order, in which the Cold War2 played a crucial role in foreign affairs. A confrontation between capitalism and socialism occurred not only in Europe but also worldwide, of which Asia had full characteristics. During the Cold War, besides the East-West confrontation, there was also the North-South conflict and the development of national liberation movements. In this context, the Korean War (1950-1953) and the Vietnam War (1954- 1975)3 also fell into these circles. Thus, these wars had similar and dissimilar characteristics. However, both the Korean War and the Vietnam War were profoundly impacted by the global Cold War.

During the Cold War period, it is assumed that all Cold War phases were not intense confrontations. Between the periods of violent struggles, there were less stressful years which politicians and diplomats called periods of “détente” (French, meaning release from tension). A wide range of researchers and scholars agreed that there were three tense and détente phases. The period of 1947-1953 was the period of Cold War formation, warming up, and getting very tense. The two systems launched an arms race, gathered forces, and confronted each other fiercely. Peace was threatened directly. From 1954 to 1962, it was a period of peaceful coexistence, beginning with the Korean Armistice Agreement and the Geneva Agreement ending the Korean War (1953) and the French-Indochina War (1954). Between 1962 and 1965, the world became tense again. In the capitalistic bloc, the White House attempted to make America great. On the other side, the Soviet Union tightened diplomatic relations with other socialist countries by erecting the Berlin Wall and basing medium-range missiles in Cuba. A period of peace lasted place from the mid-1960s to mid-1970s. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the world was full of turmoil and new forms of disagreement and tensions arose. Finally, from 1985 onwards, the Cold War came to an end.

Addressing these issues and phases helps us find differences and similarities of these conflicts during the Cold War era. From that point of view, the Korean War (1950-1953) and the Vietnam War (1945-1975) have similar and dissimilar dimensions. The importance of the Korean and Vietnamese wars go beyond their strategic connection [27].

2. Divided countries with North-South conflicts

At the end of World War II, in 1945, a series of international conferences were organised to resolve the distribution of interests and establish a new global order. Two such conferences were of importance: Yalta (February 1945) and Potsdam (July 1945), in which the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union decided to divide the Korean peninsula into two zones at the 38th parallel to disarm the fascist troops. The Soviet Union and the United States forces occupied the northern and southern halves of Korea respectively. The powers also decided to split up Indochina into two occupied zones, taking the 16th parallel as a boundary. The North was assigned to the Chinese Army, the South would be administered by British troops. Thus, a typical point in this separation of the two countries was that their destiny was decided by the superpowers (directly the Soviet Union and the United States).

The Korean peninsula formed two states with opposite political, economic, and social systems: the Republic of Korea (10 May 1948) backed by the United States, and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, or DPRK (9 September 1948) backed by the Soviet Union. The 38th parallel became a frontier dividing the Korean Peninsula as well as socialism and capitalism in Northeast Asia.

The division in Vietnam went through a more complicated process than that of Korea. In Vietnam, led by the Viet Minh, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or DRV, was proclaimed on 2 September 1945, before the Allies’ entering. Therefore, the powers were not able to set up indigenous governments like in Korea. They had to compromise with other forces to overthrow the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’s government. Thus, after the withdrawal of the British (February 1946) and the Chinese troops (September 1946), there were only two forces in Vietnam: one headed by Ho Chi Minh’s government, another by French colonialists. However, due to interventions of great powers (in various degrees), the Vietnamese resistance war against the French colonialists for the independence gradually caught up a wind of the Cold War. The Geneva conference (1954) decided to take the 17th parallel as a temporary military delimitation zone, dividing Vietnam into two regions. The 17th parallel turned temporarily from a demilitarised zone into one of the most restricted borders in the world. It represented the Vietnamese struggle as "a manifestation of the fundamental contradictions of the world, the conflict between national independence, socialism and the imperialist system, and between war and peace" [2].

The division of Korea (as well as that of Germany) began with the Allies’ intentions in dividing the outcome of World War II and then bore the imprint of confrontation between socialism and imperialism. The division in Vietnam came from a compromise between the confrontational powers (for the benefit of each nation) under the profound influence of a national liberation struggle.

Just as the destiny of Korea, the division of Vietnam by the Geneva Agreements was a common phenomenon in international relations after World War II. In general, the similarity was a confrontation between the two world systems during the Cold War, which due to an emergence of a new world order divided the world into two opposing political and social systems, each led by a superpower.

The Vietnamese people succeeded in removing the demilitarised zone at the 17th parallel, completing national liberation and reunification. The Vietnam War, after much pain and loss, ended.

The division of Korea, as well as that of Vietnam, into hostile states resulted from arbitrary decisions taken at the end of the Second World War, concerning the surrender of the Japanese and the administration of territory occupied by Japan. In these decisions, neither the Vietnamese nor the Koreans were consulted.

3. Korean War in connection with Indochina's position in the United States’ strategy

Nationalism, communism, decolonisation, and the Cold War were all parts of the Vietnam War and the Korean War. In the early 1950s, the international context changed dramatically. The two sides of the Cold War manifested firm determination. In Europe, the division of Eastern European socialism and Western European capitalism added an important "highlight" to the establishment of the two German states (the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany). In Asia, the appearance of two states on the Korean Peninsula (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Republic of Korea) deepened the trace of a confrontational world. In particular, the establishment of the People's Republic of China (1949) led by China’s Communist Party changed the world context, established a dominant position of socialism, and created a new order in Asian.

The conflicts in Korea and Vietnam stemmed from the interaction of two significant phenomena of the post World War II era, decolonisation (the dissolution of colonial empires) and the Cold War.

At that time, there were three wars in Asia: the French-Indochina War, the final phase of civil war in China, and the newly outbroken war on the Korean peninsula between the North and the South.

The climax of the tense situation in Asia was revealed when the Korean War was "internationalised". The United States and Chinese troops directly engaged in the Korean War. Thus, the war which broke out within boundaries of two regions to unify a country turned the peninsula into a "direct battlefield" between Chinese and American forces. It became a hot spot of the Cold War and reflected the confrontation between two halves of the Yalta order.

In the context of a world divided into two hostile blocs, a fragile balance of superpowers, a zero-sum game in which any advance for the communist camp was considered a loss for the "free world", previously unimportant regions such as Indochina suddenly took a considerable significance. The North Korean troops’ entering South Korea in June 1950 seemed to confirm American fears of communist advancement and heighten the importance of Vietnam [9, pp.18-21].

The Korean War and the international situation in this war were also an essential factor changing the United States’ policy on Asia in general and Vietnam in particular. It is assumed that the Korean War affected the United States’ policy towards Indochina in an indirect way but an important form. The Korean War influenced the US’ strategy and improved its priority order in Asia. Indochina was a key for the US to do what it called “protecting” Southeast Asia.

After the communist victory in China (1949) and the outbreak of the Korean War (1950), the Truman administration made the first step towards directing the US’ involvement in Indochina. The outbreak of the Korean War, together with concerns about the intentions of the Chinese communists, solidified Washington's commitment [14, p.9].

Under these subjective and objective factors, Vietnam and Korea increasingly occupied a critical position in the strategy of the United States, China, and the Soviet Union, although these regions were still not considered central areas but just "peripheral" areas of the Cold War.

Truman himself reveals the domino theory’s compelling logic: “If we let South Korea down, the Soviets will keep right on going and swallow up one piece of Asia after another”, which would eventually cause a collapse in Japan and Europe [20, p.148].

However, the Korean peninsula and Indochina were places where the "hot wars" happened fiercely, cruelly, and bloody between the two systems in the world. These events reflected an essential feature of the Cold War, in which military conflict often arose in areas not directly endangering the national security of two superpowers. It proved their own merits in the international politics of powerful countries.

The United States intervened in Vietnam to contain communism and prevent it from spreading throughout Asia. Had it not been for the Cold War, the United States, China, and the Soviet Union would not have intervened in what likely had remained a local struggle for decolonisation in French Indochina. The Cold War shaped the way the Korean War and the Vietnam War were fought and significantly affected their outcome.

"The Cold War was an early and constant preoccupation, presenting a range of problems, challenges, and opportunities… To a degree not fully evident at the time, the superpowers’ actions in Indochina in 1950 had the effect of intensifying the struggle and prolonging it, and of reducing (but not eliminating) the freedom of action of both France and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam" [12, pp.281-304].

In Indochina, the stage was already being set for the United States’ involvement in Vietnam before the Korean War broke out. A month before North Korea’s attack, the US granted a modest aid package to the French colonialists in Vietnam. While the US said it may have continued to increase in the absence of the Korean War, the outbreak of fighting on Korean peninsula certainly worked to deepen and intensify the mushrooming the United States’ will to containing communism in Indochina [19, pp.122-146]. In fact, less than a year after the Korean War ended, the United States was underwriting about 80 percent of the cost of the French War in Indochina [10, p.349]. By the mid-1960s, the United States’ policymakers looked back on Korea as a successful exercise in limited war, which encouraged them to believe that they could achieve a repeated performance in Indochina [23, p.236]. Similarity, Vietnam’s confirmation of a new policy pattern begun in Korea that went against the old policy of strictly avoiding land wars on the Asian landmass [15, pp.39-40]. The Korean War seemed the most likely factor for the United States government officially used in the historical analogies for reasons leading up to the escalation in Vietnam in 1965 [23, p.237].

The Korean conflict coloured the United States’ perceptions of the need to contain communism in Asia and influenced the Washington’s involvement in Vietnam. The North Korean entering South Korea in June 1950 seemed to confirm the United States’ fears of a communist expansion and to heighten the significance of Vietnam. "The United States never set out to win the war in the traditional sense. It did not seek the defeat of North Vietnam. On the contrary, vivid memories of Chinese intervention in the Korean War in 1950 let the administration to wage a limit war" [9, pp.18-21].

4. Internationalised wars and superpowers' involvement

The Korean War and the Vietnam War were power games between the United States, the Soviet Union, and China during the Cold War. The United States’ perception of the Soviets’ role in the outbreak of the Korean War and the latter’s aims in Korea thus played an essential role in escalating and shaping the Cold War [26].

The Korean peninsula had a significant position in the United States’ strategy. As President Truman said in proposing the “little ECA” for Korea to the Congress on 7 June 1949:

“Korea has become a testing ground in which the validity and practical value of the ideas and principles of democracy which the Republic is putting into practice are being matched against the practices of communism which have been imposed on the people of North Korea. The survival and progress of the Republic towards a self-supporting, stable economy will have an immense and far-reaching influence on the people of Asia. Moreover, the Korean Republic, by demonstrating the success and tenacity of democracy in resisting communism, will stand as a beacon of the people of northern Asia in opposing the control of communist forces which have overrun them. If we are faithful to our ideals and mindful of our interests in establishing peaceful and prosperous conditions in the world, we will not fail to provide the aid which is so essential to Korea at this critical time” [30].

The Korean War was one of the principal triggers for the expansion of the Cold War, and it embraced the continuing Vietnamese War into that conflagration, which marked the anti-colonial and anti- communist wars of the 1950s. The Korean War also marked the return to the massive industrial warfare of the Pacific and European Wars, with substantial investments in air power, armour, and heavy artillery. The rise of the People's Republic of China brought the United States’ attention back from Europe to Asia, leading to the allocation of a multi-million dollar defence expenditure to the "general area of China".

Sixteen countries provided military assistance, and at peak strength, the United Nations Command forces numbered about 400,000 soldiers from the Republic of Korea, 250,000 from the United States, and 35,000 from other nations [24, pp.421-433].

At first glance, the maximum of 537,000 US servicemen in Southern Vietnam in 1968 dwarfed the peak of 326,863 soldiers in South Korea in 1953, and the density of the commitment to Korea exceeded Vietnam, 329 to 302 [13, pp.635-656].

The nature of the war, on the Vietnamese side, was still a struggle to defend the independence of the motherland, protect territorial integrity and unification of the country. However, in the context of the international division of the two sides, the Vietnam battlefield also inevitably became a place where great powers gained their influence. China supported the Democratic Republic of Vietnam; the United States and its allies assisted the Republic of Vietnam.

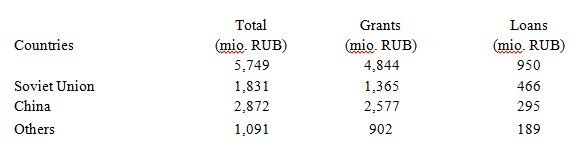

When the Vietnam War became a large- scale one, and the first US combat troops arrived in Southern Vietnam in 1965, the Soviet Union moved from being an "observer" to providing direct assistance. The communists increased economic aid to Vietnam to consolidate its position in the strategic battle with the United States in the East-West confrontation. In the period between 1954 and 1965, the total amount of non-refundable aid and long-term loans from China to Vietnam was worth 439 million roubles (287.5 million of that were grants, 151.5 million were loans). In the period from 1966 to 1971, the total amount of aid was 1,336 million roubles, of which 864 million were grants and 472 million were long-term loans [4].

The spirit and attitude of the communist economic aid to Vietnam had different characteristics. Grants were only provided during the period of the United States’ direct involvement in the war (1965-1972). In the period of the implementation of the first five-year plan (1961-1965) and the period of 1973-1975, communist economic assistance was reduced in the numbers of direct grants and changed to long-term loans, aiming at economic cooperation on the principle of mutual benefits and facilitated repayment of loans.

Table 1: Communist Economic Assistance to Democratic Republic of Vietnam (1955-1974)

Source: Situation of economic relations between Vietnam and foreign countries from 1955 to 1974, Dossier 32, State Planning Committee Folder, Vietnam National Archive Centre No. 3.

The United States’ military aid to the Saigon government in the period 1955-1960 was USD 1,028.9 million, USD 1,177.9 million for the period 1961-1964, USD 3,420.0 million for the period of 1965- 1968, and USD 12,311.8 million for the period 1969-1975. For the whole period 1955-1975, the United States’ government provided USD 17,939.1 million on military aid to the Republic of Vietnam [1, p.486].

It is notable that the period in which Vietnam received the highest economic aid was also the period that the United States’ combat troops in Vietnam were at the highest level [3].

Given the growing threat from the United States of the escalation of military offense against the DRV, Beijing expressed its concern over a possible open confrontation with Washington. Meanwhile, air strikes against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam shifted to the China- Vietnam border area. The United States adopted a policy that allowed its air strikes to hit any force that blocked American air routes, even those based in China [18]. When Beijing leaders became more concerned about the rising security threat from the escalation of the war by the United States, China increased its support for Vietnam, despite knowing that such action could lead to a total war against the United States.

From this analysis, it can be said that communist economic aid to Vietnam was a result of a confrontation between the capitalist and socialist systems. Thus, in the period from 1965 to 1968, the level of intervention of the United States, the Soviet Union, and China was pushed to the highest level. After the United States planes bombed Hai Phong (1966), which is a city close to China's border, in an official statement dated 7 September 1966, China announced that "the United States military's attack against Vietnam was an attack against China," warning that Washington could have "made a serious historic mistake" if it underestimated China's determination to support Vietnam [21, pp.7-10].

While asserting the attitudes of superpowers taking their benefits from Vietnam’s struggle, on meeting with Zhou Enlai, the Secretary-General of the Communist Party of Vietnam, Le Duan, said: "The relationship between China and Vietnam will exist not only in the struggle against the United States but also in the long future ahead. Even if China does not help us as much, we still want to maintain close relations with China, as this is a guarantee for our nation's survival" [29].

Thus, the level of intervention of the United States, the Soviet Union and China was pushed to the highest level. Therefore, the Vietnam War became increasingly severe and part of East-West conflict, with the international character of the conflict becoming more apparent. The involvement of the United States, the Soviet Union and China in the Vietnam War reflected the complicated relationship between the two superpowers and had a profound impact on the nature and progress of the war as well as on Vietnam itself. However, it is also increasingly clear during the Cold War that Vietnamese leaders turned the rivalry among the contemporary superpowers to their advantage in their struggle for national liberation [17, pp.1-16].

5. Hot Wars in a Cold War

Resulting from interests of great powers with two confronting systems headed by the United States and the Soviet Union, the capitalist and socialist systems were established after World War II. The two countries played decisive roles which affected all international relations, involving many regions and nations in a new form of war - the Cold War. Although it was called the "Cold War", the atmosphere of the world was not "cold" at all. "Hot wars", i.e. local conflicts between the United States and the Soviet allies happened in many regions of the world. Behind that, it had hands, shadow, and data, implicit plans of great powers (in Indochina, the Korean Peninsula, the Middle East). With the formation and hostility between capitalist and socialist systems, Vietnam's unification struggle was put in a spiral and affected by the profound influence of this context.

In Asia, the concept of “Cold War” is more complicated. Its origins in Vietnam involved policies pursued by the colonial authorities returning to the region after World War II, their relations with great powers, as well as the agendas pursued by the local nationalist forces and communist parties of the region [8, pp.441-448]. The Cold War in Asia reflected by conflicts and diplomatic hostilities across the borders of the two blocs. It is assumed that the Cold War is characterised by hot wars and was one of the most crucial events in Asia in the second half of the twentieth century. The Cold War had a significant impact on decolonisation and nation-building in Asia. For long periods of time, many Asian countries experienced the Cold War.

Tensions and hostilities marked the relationships not only among Asian members or the US and the Soviet Union but also between North and South in each country in some cases [25, p.7].

During the Cold War, nation-state building and socio-economic development were two independent, and interrelated processes transforming Asia. Nation-state building began with decolonisation. It is assumed that some Asian countries took the Cold War as a chance to secure American or Soviet aid for their nation-building programmes [6], [16], [5]. Nation-state building also went along with numerous civil wars interacting closely with the Cold War but followed their particular logic, such as Korea (1950-1953), Vietnam (1954- 1975), Laos (1958-1975), and Cambodia (1970-1975).

The Korean War is an immensely crucial event which was the first armed war of the Cold War, the first United Nations War, and the only time that major military powers have clashed on the battlefield since World War II [24, pp.421-433].

On 25 June 1950, the combat troops of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea) made advancement across the 38th parallel.

On 7 July, the UN Security Council established a unified military command under the United States. Eventually, sixteen nations contributed forces. By the spring of 1951, these included 12,000 British, 8,500 Canadian, 5,000 Turkish, and 5,000 Filipino soldiers [22, p.102].

Both wars left huge losses. According to incomplete statistics of Vietnam, 1,1 million soldiers died, 600,000 soldiers were wounded, 300,000 soldiers went missing, and two million civilians were killed. There are also about two million people who suffered from disabilities, two million who came in contact with toxic chemicals, and nearly 500,000 children with deformities due to chemical warfare4.

The Korean War, in which 54,000 US troops were killed, forms the background against which the connection of the United States to the hostilities in Indochina at that time was played out [7, p.99].

The American losses in Korea amounted to 144,000 casualties, MIAs, and POWs, whereas the North Koreans and their Chinese allies together lost over 1,2 million people [7, p.140].

One estimate places the casualties toll at 750,000 militaries and 800,000 civilians. Of the military deaths, 300,000 were from the North Korean Army, 227,000 from the Republic of Korea Army, 200,000 from Chinese volunteers. About 37,000 Americans and 4,000 UN allies were killed. Civilian casualties are hard to estimate. On the high end, one UN estimate places the number of South Koreans who died of all causes including disease, exposure, and starvation at 900,000. North Korean casualties were probably higher [22, pp.109-110].

Of the 132,000 North Korean and Chinese military POWs, fewer than 90,000 returned home. Of the 10,218 Americans captured by the communists, only 3,746 returned; the remaining 6,472 perished. Perhaps four times that number of South Korean prisoners died. RoK forces sustained some 257,000 military deaths, while the United States war-related deaths numbered 36,574, and forces under the United Nations’ command suffered 3,960 casualties. The DPRK has released no casualty figures, but its military deaths are estimated at 295,000. Chinese deaths from all causes might approach one million. Perhaps 900,000 South Korean civilians died during the war from all causes5.

The United States Air Force dropped 7,5 million tonnes of bombs in Indochina, three times as much as in World War II (2,1 million tonnes), 47 times more than in Japan (160,800 tonnes) and more than ten times than in the Korean War (698,000 tonnes) [1, p.498].

The Korean War and the Vietnam War were all products of the Cold War, with the involvement of superpowers with their calculational strategies, differently expressed in each region and each country.

The conflation of the Cold War and the decolonisation provided opportunities as well as challenges to indigenous nationalists and European powers alike, hastening decolonisation in some territories and prolonging that process in others.

Thanks to the Cold War, national movements in Asian attracted superpowers’ backing by drawing to their respective geopolitical concerns and fears. The Cold War impacted the course of decolonisation in Southeast Asia extremely. However, even as the Cold War influenced the future destiny of Southeast Asia in an era of decolonisation, it was transformed by its raging revolutionary fires into a "hot" Cold War. It was assured after a series of exogenous events in East Asia, beginning with the victory of communism in China in October 1949, and followed shortly thereafter by the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950. These events conspired to fundamentally affect its tenor and consequence. By the end of the 1950s, Asia in general and Indochina in particular, had become not just another regional theatre of the Cold War but the crucial main front in Asia where the looming and even "hotter" contest to finally resolve the outcome of the

two competing ideological systems was destined to be decided [11, p.4].

The Cold War also had impacts on the Vietnam War. In contrast, the Vietnam War affected trends of the Cold War at some points. The United States decided to intervene, causing the Cold War to push Indochina into a hot spot. Vietnam accepted to sign the Geneva Agreements contributing to creating more peace and harmony. The Vietnamese struggle step by step promoted national liberation movements in the Third World, and became a new hot spot in the Cold War. Vietnam was a factor pushing Sino-American rapprochement. These complex relationships contributed to promoting international peace at that time.

6. Dissimilarities

In fact, there were two Cold Wars in Asia, the one between the United States and China as well as the Asian dimension of the United States-Soviet Union Cold War. Also, there were two "hot" wars in which the United States military forces were directly involved - the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Asia was beset with such conflicts and two full-fledged battles with the United States as a significant participant. The Cold War in Asia is a misnomer unless it merely means that the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a power struggle in Asia but avoided, as in Europe, a direct military engagement.

The Vietnam War differed from the Korean War. It developed in unique circumstances and changed in nature. It was believed that behind the North Korean attack stood Chinese and Soviet decisions.

However, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was neither an agent of the Soviet Union nor of China. Given China's advocacy of anti-American revolutions for national liberation, it is more plausible to argue that the North Vietnamese and their southern allies were under Chinese influence. In fact, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was an independent actor.

The Korean War and the Vietnam War were all products of the Cold War, with calculated involvements of superpowers. However, in each region, each country, it turned colours in different ways.

The Korean War and Vietnam War were hot wars in the Cold War. However, the evolution of the war reflected international conflicts, becoming the battlefield of fierce struggles between superpowers. This confrontation related directly to the strategic calculations of the United States, the Soviet Union, and China and the involvement of these countries in these clashes.

Due to the political situation and geographic features, the wars’ purposes were different: The Vietnam War was a struggle to preserve unity and territorial integrity - a fundamental part of national rights. The Korean War was a direct engagement between the two confronting blocs, namely China, Korea, and the United States. It led to different results that directly affected countries and regions in postwar years.

In addition to its international character, the wars in Korea and Vietnams are North- South struggles. In both cases, the division of the countries into two zones were significant reasons leading to the breakout of the war. The split led to a fierce confrontation between the two regions, followed by the two poles in the two areas. As a result, gaps between the two regimes deepened, and a devastating war broke out.

The Korean War began as a civil war, leading to a confrontation between superpowers (China, the Soviet Union, and the United States). From this event, the relationship between the two blocs worsened. After the 37-month long war, millions of people were killed, and the Korean peninsula returned to its original state - back to the dividing line that the Soviet Union and the United States drew upon at the end of World War II. The Korean War left massive consequences for both North and South Korea. Besides the losses, this war led to suspicion, even hostility between the South and North. The Korean Armistice Agreement was the only military ceasefire, but not a political resolution which resolved the issue of national rights, including the unification of the Korean peninsula. This is a fundamental difference from the 1954 Geneva Agreements on Indochina. It is also the longest lasting armistice that should have been replaced by a permanent peace treaty for the Korean Peninsula. The mutual suspicion and the ideological opposition between North and South Korea were both symbols of confrontation. The conflict of the Cold War had a profound effect on the Korean peninsula. The two political regimes in the two regions had two different ideologies, even opposing each other, so their perception was utterly different.

The Korean War and the Vietnam War differed in their nature and participants of the war. The Korean War happened in two phases. In the first phase, foreign allies did not have crucial roles. During the second phase, nearly 100,000 Chinese troops were fighting against the forces of the United Nations led by the United States. Thus, the first phase was a local conflict. The second phase was an "internationalised" war on the Korean peninsula.

The Korean War occurred when the East-West and the North-South conflicts were at the highest level, causing a bloody encounter. The result of the Korean battle was the Armistice Agreement, which meant not ending the war.

After the French failure to stabilise Indochina in 1954, the United States followed in the French footsteps and deployed their combat forces to contain the spread of communism in Indochina. The Vietnam War converted a part of the Cold War, and the United States used Vietnam as a card to gain global strategic interests, and to contain the influence of the Soviet Union and China. The United States used all kinds of weapons to achieve victory. In contrast, Vietnamese people also accepted all hardship and sacrifice to gain their independence, freedom, and reunification. For their obligations to allies, for their interests, the Soviet Union, China, and other socialist countries assisted Vietnam in this struggle. The peace and national liberation movements fully supported Vietnam, including also American people. Thus, the French-Indochina war (1945- 1954) and the Vietnam War (1954-1975) were leading international events of great attention for all humanity over an extended period.

The Democratic Republic of Vietnam took advantage of the Cold War in other ways. Until 1964, both major communist powers had been consummate pragmatists.

However, the US escalation forced them to make tough choices to assist the DRV's efforts to reunify the nation. In total, the Soviet and Chinese aid estimated at more than two billion USD. It helped to neutralise the United States’ air attacks, replace equipment lost in the bombings, and helped Hanoi to send more troops to the South. "The fact that the Soviet and Chinese supply almost all war material to Hanoi… [has] enabled the North Vietnamese to carry on despite all our operations" [9, pp.18-21].

The Vietnam War exposed internal conflicts leading to a fierce struggle between two political regimes. After the Paris Agreement (January 1973), the United States troops withdrew from Vietnam, with the only remaining forces being Vietnamese. The war characterised a civil conflict, but overall, it was a resistance to unify the nation.

At the same time, the Vietnam War occurred in the context of global bipolar order. The North followed the socialist path supported by the Soviet Union, China, and other socialist countries. The South followed the capitalist path with aid from the United States and capitalist countries. Thus, the battlefield in Vietnam became the confrontation between the ideologically opposing systems. This situation led to the "internationalisation of the Vietnam War" with the concern of the great powers. The Vietnam War reflected challenges and strength of both opposing sides.

Whereas the Korean War (1950-1953) was a confrontation between the United States and the People's Republic of China, the Vietnam War was only a direct combat of the United States troops and its allies with Vietnamese forces in both regions. The Soviet Union and China strongly supported the DRV with regard to arms, ammunition, warfare facilities, expert teams, and anti-aircraft guards in some northern provinces. Neither Soviet nor Chinese soldiers faced the United States and Saigon troops on the battlefield.

Due to the characteristics of the situation and nature of the war, the Vietnamese struggle was associated with anti-war movements all over the world. Vietnam tried to gain support from all nations, especially anti-war movements of American people. Thus, Vietnam consolidated and expanded its global sphere, and built up the pressure on the United States’ government in the international, diplomatic, and military arenas. Therefore, Vietnam created its legitimacy of the struggle.

Although China and the Soviet Union supported Vietnam hugely, they could not control Vietnam's military and political policies. Hanoi determined its internal and foreign affairs itself.

Since then, each war extended its effects in various ways. The Vietnam War affected the non-aligned movements, receiving the support of people all over the world. The Korean War did not have that considerable influence.

This difference created a political advantage for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, placing the conflict between the Vietnamese struggle and the United States interference on the top. Therefore, the goal of the war was to fight against the aggression, to raise a banner of national liberation, thereby uniting people, including a large number of people living in the southern part of Vietnam.

Meanwhile, American troops caused massacres, so they lost their loyalty and public support back in the US as well as in many countries around the world. Thus, in the United States, the anti-war movements were calling for peace and unity.

7. Conclusion

From these above mentioned points, it can be seen that the Vietnam War brought simultaneously three characteristics which significantly differ from the Korean War: the national liberation of Vietnamese people, the opposing between the two regimes in Northern and Southern Vietnam, the confrontation between the two blocs in the world. It solved the conflict between the Vietnamese people and US imperialists, between socialist and capitalist regimes, as well as the dispute between the Soviet Union and China. This split turned Vietnam into a place to win the other's influence. Thus, Vietnam became a focus of the struggle not only between the two blocs (capitalist and socialist) but also within the socialist camp.

However, the most significant difference between the Vietnam War and the Korean War is the final outcome of this struggle. Despite being affected by the global Cold War, the Vietnamese people successfully united the country. It was a result of the Vietnamese determination and sacrifices, from which the Vietnamese Communist Party conducted the right leadership leading to the success. Meanwhile, the Korean War was one of the bloodiest clashes in modern history and strongly influenced by external factors. The split of the Korean Peninsula continues, and the remnants of the Second

World War and the confrontation between the two sides in the Cold War have so far not been resolved. Therefore, the Korean peninsula remains in a state of being divided into two states. This division is a debt that the relevant powers need to be responsible for towards the Korean people.

Naturally, wars at any time, in any territory or country, mean losses and sad stories. The conflicts in Vietnam and Korea are very different, but they have this in common: as in warfare, it’s the civilians who suffered most of all. We should remember the wars, not to repeat them but instead maintain and consolidate peace as well as build up the friendship between people all over the world.

Notes

* Institute of History, Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences.

1 This paper was edited by Etienne Mahler.

2 The Cold War was defined in terms of the structure of international relations: the rivalry between the United States-led Western liberal democratic bloc and the Soviet-led Eastern communist bloc which shaped the basic structure of international relations (Tadashi Aruga – Professor, Hitotsubashi University - The Cold War in Asia).

3 There are some arguments about the date of the "Vietnam War" which was also called "the Second Indochina War" (1954-1975) or "the Vietnam Wars (1945-1975) (including the first and the second Indochina war). In this paper, the author uses the term “Vietnam War (1954-1975)” to refer to all the wars happening in Vietnam’s territory during this timeframe.

4 The number was calculated based on that of people receiving social welfare from the government. The real numbers of deaths and wounded people go far beyond [1, pp.576-580].

5 Casualty figures have been widely disputed, the best analysis can be found in Allan R. Millet, “Casualties”, Encyclopedia of the Korean War.

References

[1] Ban chỉ đạo tổng kết chiến tranh trực thuộc Bộ Chính trị (2015), Chiến tranh cách mạng Việt Nam 1945-1975: Thắng lợi và bài học, Nxb Chính trị quốc gia - Sự thật, Hà Nội. [Committee under the Politburo for Summing up National Revolutionary War (2015), Vietnam's Revolutionary War, 1945-1975: Victory and Lessons, National Political Publishing House, Hanoi .

[2] Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam (2004), Văn kiện Đảng toàn tập, t.35, Nxb Chính trị quốc gia - Sự thật, Hà Nội. [Communist Party of Vietnam (2004), The Complete Collection of Party Documents, Vol. 35, National Political Publishing House, Hanoi .

[3] Thông tấn xã Việt Nam (1973), Tài liệu về miền Nam. [Vietnam News Agency (1973), Documents about the South].

[4] Trung tâm Lưu trữ Quốc gia III, Phông Phủ tướng, Hồ sơ 8767, Báo cáo về tình hình viện trợ kinh tế và kỹ thuật của Trung Quốc cho Việt Nam từ 1955 đến 2/1970. [Vietnam National Archive Centre No. 3, Prime Minister Folder, Dossier 8767, Report on Chinese Economic and Technical Assistance to

Vietnam from 1955 to February 1970 .

[5] Ragna Boden (2008), “Cold War Economics: Soviet Aid to Indonesia”, Journal of Cold War Studies, Vo. 10, No. 3.

[6] Gregg A. Brazinsky (2007), Nation Building in South Korea: Koreans, Americans, and the Making of a Democracy, University of North Carolina Press.

[7] Frank Cain (2017), America's Vietnam War and Its French Connection, Routledge, New York.

[8] Karl Hack, Geoff Wade (2009), "The Origins of the Southeast Asian Cold War", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3.

[9] George C. Herring (2004), “The Cold War and Vietnam”, OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 18, No. 5.

[10] Burton I. Kaufman (1986), The Korean War: Challenges in Crisis, Credibility, and Command, Temple University Press.

[11] Albert Lau (2012), Southeast Asia and the Cold War, Routledge.

[12] Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad (2010), History of the Cold War, Vol II: Crises and Détente, Cambridge University Press.

[13] John L. Linantud (2008), "Pressure and Protection: Cold War Geopolitics and Nation- Building in South Korea, South Vietnam, Philippines, and Thailand", Geopolitics, Vol. 13, No. 4.

[14] Fredrick Logevall (2013), The Origins of the Vietnam War, Routledge.

[15] Callum A. MacDonald (1986), Korea: The War before Vietnam, The MacMillan Press Ltd.

[16] Matthew Masur (2009), “Exhibiting Signs of Resistance: South Vietnam’s Struggle for Legitimacy, 1954-1960”, Diplomatic History, Vol. 33, No. 2.

[17] Edward Miller and Tuong Vu (2009), "The Vietnam War as a Vietnamese War: Agency and Society in the Study of the Second Indochina War", Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3.

[18] New York Times, April 27, 1966.

[19] Michael J. Nojeim (2006), "US Foreign Policy and the Korean War", Asian Security, No. 2 (2).

[20] Arnold A. Offner (1999), "Another Such Victory: President Truman, American Foreign Policy and the Cold War", Diplomatic History, Vol. 23, No. 2.

[21] Peking Review, September 16, 1966.

[22] Michael J. Seth (2010), A Concise History of Modern Korea: From the Late Nineteenth Century to the Present, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc, United Kingdom.

[23] William Stueck (2002), Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History, Princeton University Press.

[24] Spencer C. Tucker (2010), “The Korean War, 1950-1953: from Maneuver to Stalemate”, The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, Vol. 22, No. 4.

[25] Tuong Vu, Wasana Wongsurawat (2009), Dynamics of the Cold War in Asia - Ideology, Identity, and Culture, Palgrave Macmillan.

[26] Kathryn Weathersby (2011), Soviet Aims in Korea and the Origins of the Korean War, 1945-1950: New Evidence from Russian Archives, Working Paper No. 8, Cold War International History Project.

[27] Mel Gurtov (2010), "From Korea to Vietnam: The Origins and Mindset of Postwar U.S. Interventionism", The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 8, Issue 42, No. 1, https://apjjf.org/-Mel-Gurtov/ 3428/article.pdf, retrieved on 26 May 2019.

[28] Allan R. Millet, Korean War (1950-1953), Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica. com/event/Korean-War, retrieved on 26 May 2019.

[29] Wilson Center (1966), “Discussion between Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping, Kang Sheng, Le Duan and Nguyen Duy Trinh”, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, CWIHP Working Paper 22, "77 Conversations", http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/documen t/113071, retrieved on 26 May 2019.

[30] https://www.trumanlibrary.org/whistlestop/stu dy_collections/korea/large/documents/B43_18 -04_03.jpg, retrieved on 26 May 2018.

Sources cited: JOURNAL OF VIETNAM academy OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, No. 1 (195) - 2020