Assoc.Prof.Dr. Nguyen Huy Hoang

Institute for Southeast Asian Studies, Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences.

Abstract: Rapid development of ASEAN - China economic relations since the early 1990s is thought to play an important role in strengthening strategic partnership between the two sides. By analysing the practice and trends of ASEAN - China economic relations as well as the association of such relations with the partnership between the two parties, the paper points out that besides promoting the strategic partnership, ASEAN - China economic relations have created certain impediments such as reducing the trust of ASEAN in China. For economic relations to become the factor promoting ASEAN - China strategic partnership, both sides need to find the way to improve the mutual trust. Particularly, China needs to win ASEAN’s trust in its actual motive when promoting the relationship between the two sides.

Keywords: ASEAN, China, economic relations, strategic partnership.

Subject classification: Economics

1. Introduction

In July, 2018, ASEAN and China marked the 15th anniversary of establishing their strategic partnership. Bilateral relations between the two sides continue to develop through the ASEAN - China strategic partnership vision 2030, passed in ASEAN - China Summit organised on 14 November, 2018. In accordance with the vision to 2030, the framework of ASEAN - China developed in 2013 was elevated from the “2+7” cooperation framework to “3+X” cooperation framework [15]. Specifically, the pattern of “2+7” touches up two perceptions and seven petitions2 while the modality of “3+X” presents the development relationship based on three pillars and one unidentified cooperation programme. These three pillars are political security, economic affairs and human exchange.

Economic cooperation is a crucial area promoting ASEAN - China vision on the strategic partnership. Apart from promoting the two-way trade of goods and services, China pays ever-more attention to the FDI increase and infrastructure construction in ASEAN countries. Meanwhile China’s increasing attention to small ASEAN countries is highly spoken of, the vision of ASEAN - China strategic partnership to 2030 also needs to mind concerning issues of ASEAN countries such as increasing trade deficit in the trade relationship with China and loss of political autonomy due to the extensive reliance on China in terms of economic affairs.

2. China - ASEAN bilateral economic relations

2.1. Trade

Economic relations between China and ASEAN have grown steadily since the middle of the 1990s. Bilateral trade in goods went up from USD 13.3 billion in 1995 to USD 113.5 billion in 2005 and up to USD 514.8 billion in 2017 [22]. During this period, the growth rate of two-way trade reached about 18% per year, which was impressive in comparison to the growth rate of about 7% per year in ASEAN’s trade with the world.

The value of two-way trade in services also increased rapidly in the period of 2005-2016. This value rose from USD 161 billion to USD 657 billion for China and from USD 252 billion to USD 643 billion3 for ASEAN. Recently, ASEAN has reached the trade surplus of USD 8 billion and China has witnessed the trade deficit of USD 243 billion. Such statistics indicates that China has imported many services from other parts of the world rather than ASEAN. With regard to bilateral trade, China has exported technical services and labour to ASEAN and imported transport, finance and construction services from ASEAN countries [9]. The trade in tourism services is huge and continues to potentially show increase. In 2017, about 20.5 million Chinese tourists came to ASEAN countries (about 18% of the total tourists entering ASEAN) and 10.5 million tourists from ASEAN countries flocked to China (8% of the total tourists entering China) [23], [13].

The proportion of China’s investment flow to ASEAN has increased from 3 to 10% (USD 2-9.8 billion) while ASEAN countries are moving towards the finalisation of their economic community and receiving a huge amount of FDI. The production network promoting closer cooperation has increased investments from China, especially in the manufacturing of ASEAN. On the contrary, the FDI flow from ASEAN to China has tended to go up with Singapore as the front runner out of the crowd. Economic relations between the two sides is ever-more consolidated by ASEAN - China Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA). Both sides signed this agreement in 2004 and started the roadmap of reducing taxes on some products between ASEAN-6 countries and China in 20104 and between CLMV countries (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam) and China in 2015. The countries had passed the Early Harvest Programme (EHP) before forming the FTA. Accordingly, China had decided to reduce taxes immediately for ASEAN members on some agricultural products.

The service and trade agreement was signed between the two sides in January, 2007. The liberalisation in tourism is very note-worthy for the mutual interest of both sides [6]. Although the trade presence of multinational and cross-border companies is sensitive, ACFTA promises to encourage investment flows in areas such as business, construction, tourism, transport and education. Investment agreement between the two sides was inked in 2009 to promote cooperation by enhancing the transparency of regulations and protecting the interest of investors. ACFTA was then elevated in 2016 with renovations in fields such as rules of origin, trade facilitation, service liberalisation and investment promotion.

- Comparisons of ASEAN - China trade in goods

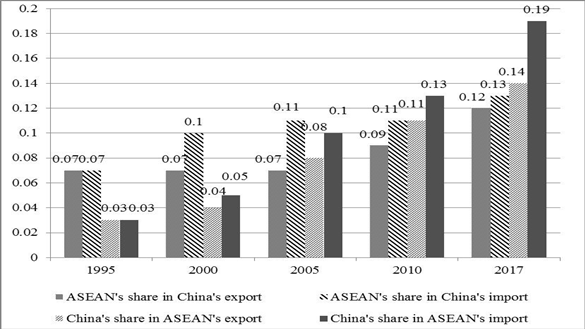

The relative presence of ASEAN in China’s market and vice versa concerns ASEAN countries. According to Figure 1, the presence of ASEAN goods in China’s trade basket has increased over time. The relative import of China from ASEAN, after going up from 7% to 11% in the period of 1995-2005, has been continuously improved in the post-ACFTA period (after 2010). However, the presence of China’s goods in the trade basket of ASEAN increased by five to six times in the period of 1995-2017. In the post-ACFTA period, the market share of China in ASEAN’s import soared much more rapidly than in ASEAN’s export. This proved that Chinese enterprises penetrated into ASEAN market more efficiently than enterprises from other countries.

Figure 1: Trade Exchange between ASEAN and China, 1995-2017

Source: Calculations from the database of CEIC Data Company Ltd (CEIC).

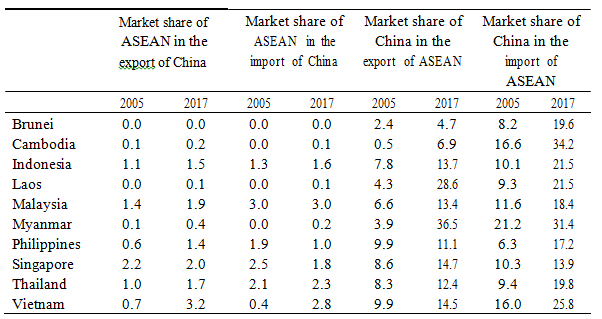

According to statistics in Table 1, the separate market shares of ASEAN countries in China’s import and export are quite humble. The statistics shows that the penetration of Malaysia into China’s market is the highest among ASEAN countries due to China’s increased import of petroleum from Malaysia; meanwhile, the market share of Singapore in China’s trade basket has reduced due to the declining role of this country in exporting petroleum to China. Conversely, the presence of China in the trade baskets of all ASEAN countries increased in the period of 2005-2017. In the recent years, the goods export of China has been the highest in Cambodia, followed respectively by Myanmar and Vietnam.

Table 1: Market Shares of ASEAN Countries in the Trade Basket of China and Vice Versa

(Unit: %)

Source: Calculations from the database of CEIC.

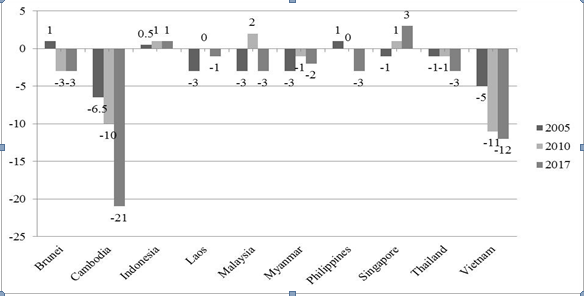

The ever-more presence of Chinese goods at ASEAN market concerns ASEAN countries because they face not only the trade deficit with China, but also the increasing possibility of political tension. Figure 2 indicates that apart from Singapore, all other ASEAN countries experienced trade deficit with China in 2017. Meanwhile Brunei, Indonesia and Philippines have experienced trade surplus with China before facing trade deficit recently, Vietnam and Cambodia witnessed their trade deficits with China during the period of 2005-2017. This posture proves that the export of China to ASEAN countries, which gained advantages in the past, continues to be strengthened after ACFTA was signed in 2010.

For Indonesia, from the beginning, this country has shown its concerns about ACFTA. It is because the trade balance of Indonesia has been declined in production area, which leads to the political tension within the country. Indonesia was not satisfied with the discrimination posed by China. Specifically, in accordance with EHP, Indonesia has to pay higher tax than Malaysia and Singapore for processed cacao imported from China. Therefore, Indonesia considered to re-negotiate a part of ACFTA (220 kinds of tax on iron, steel, textile, garment and footwear industries) but it was not successful. After that, although China promised to invest in the infrastructure of Indonesia and increase the import from Indonesia. However, the concern about job loss caused by the import of low-quality goods from China has led to public demonstrations in many cities of Indonesia.

Hence, although the economic partnership between ASEAN and China is often viewed as positive, the likelihood of economic conflicts does exist due to differences in the development scale and plan between the two sides. This affects the comprehensive ASEAN-China strategic partnership in the future.

Figure 2: The Trade Balance of ASEAN Countries with China (% GDP)

Source: Calculations from the database of CEIC.

2.2. China’s Investment in infrastructure of ASEAN within the framework of ACFTA

In addition to trade relations, China’s investment in infrastructure of ASEAN countries plays a crucial role in enhancing and promoting the connection between ASEAN and China. To hit that target, the two sides cooperated to develop the traffic and transport system in a holistic manner in 2003 after both sides acknowledged that “developing an integrative traffic network will create important infrastructure for ASEAN-China free trade area” [24]. In 2016, the two sides ratified the strategic plan for cooperation in transport between ASEAN and China and decided to find solutions for cooperation in shared priorities between the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025 (MPAC 2025) and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Both sides agreed to promote transboundary projects such as Kunming - Singapore Railway Connectivity, Lancang - Mekong Cooperation, ASEAN - China Port Cities Cooperation Network and ASEAN - China Information and Logistics Cooperation.

In addition, ASEAN countries and China are currently having cooperation projecting in areas such as electricity, traffic and telecommunication. Both state-owned and private multinational enterprises of China are actively taking part in infrastructure field of ASEAN. Specifically, in CLMV region, Chinese companies are the biggest investors in projects on building hydropower plants, dams, roads, bridges, sea ports and railway networks. In addition, at the proposal of Mr. Wen Jiabao, China’s former Prime Minister in 2009, China -ASEAN Investment Cooperation Fund has invested in ASEAN since 2010. What is more, from January, 2016, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) started to provide loans for infrastructure development to ASEAN members. Indonesia is the top country, followed by the Philippines and Myanmar, in the list of beneficiaries of AIIB’s loans.

Besides positive postures in the cooperation between the two sides, there remain concerns about the fact that China’s investment can hurt the economies of countries receiving loans from AIIB or China - ASEAN Investment Cooperation Fund. China’s support is not only the financial provision, but it also expands to issues such as project management, equipment and building material supply and labour. This posture creates worries for economies receiving funding from China. For instance, in Cambodia, many local people complain that new jobs generated by China’s investment are only for Chinese immigrants. Even small local enterprises are hurt when Chinese workers tend to buy daily essential stuff from Chinese-owned shops [16]. Similarly, local people in Indonesia complain that Chinese companies often bring along “their workers and machines, creating conflicts with local people” [20].

Projects funded by China are also evaluated as having negative impacts on environments of investment receivers. Recently, Thailand has decided to speed up the approval of China’s project investing in the power plant which was deemed to go against the law on environment protection of this country [21].

Interests of China when investing in big projects such as Forest City in Malaysia, Sihanoukville Port City in Cambodia, China - Laos Railway and especially Kyaukpyu Economic Special Zone in Myanmar are considered disadvantages for national debts of investment receivers because it is related to the ability to refund debts and other strategic risks that these countries have to face in the future. Notably, for Cambodia and Laos, China accounts for 50% of the total debts of these two countries. This dependence forces Cambodia to take into consideration political and diplomatic interests with China through costs that ASEAN countries have to suffer from [18]. In the future, once the debt burden exceeds their stamina, these countries may have to use state-owned assets such as deep water ports or oil and gas mines to refund the debts for China. This is likened to a “debt trap”, through which Beijing can get strategic assets. Therefore, ASEAN countries have to take extra precautions in accessing to big investments from China.

3. The role of ACFTA in China - ASEAN strategic partnership

ASEAN and China started the “strategic partnership for peace and prosperity” in 2003. Acknowledging the complexity and considerable changes in the global economy, the countries realise that such cooperation, including in political, security, economic and social areas plays an important role in serving the short-term and long-term interests of both sides [11]. Especially in economic cooperation, ASEAN and China agree to boost ACFTA to enhance cooperation in agriculture, human resource, investment and information technology. However, there are still outstanding questions, namely “can ACFTA be promoted further?” and “can the achieved results of economic link make contributions to the enhancement of strategic partnership between the two sides?”.

ACFTA was first put forward by Mr. Zhu Rongji, China’s former Prime Minister in 2000. At that time, many ASEAN countries were suffering from negative impacts of 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis and had to face the serious fall in their economic growth. Simultaneously these countries felt uncomfortable with the accession of China to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001 because China could thereby attract the majority of FDI in the region. To ease such tension, ACFTA is considered the solution helping ASEAN countries and China to have opportunities to access to the market of each other. Gaining on that ground, China has set objectives to help ASEAN countries through their emergence [10]. The benefits of signing ACFTA are shown more clearly after the global economic crisis in 2008. When the economic growth of western countries was slowing down, ACFTA became the mean of strengthening the economic cooperation among countries which were thought to play a crucial role in promoting the global economic growth. Therefore, on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of ASEAN-China strategic cooperation in 2013, Mr. Li Keqiang, China's Prime Minister, proposed the “2+7” cooperation framework for the next decade (2013-2023). In that pattern, two is enhancing the strategic confidence and economic cooperation in a more intensive and extensive manner and seven is cooperation areas in the framework of ACFTA and better construction of infrastructure5. Members then agreed to upgrade ACFTA by improving conditions to access to the overall market and the trade balance between the two sides as well as expand scope and area of the cooperation framework. ACFTA signatories set the objective of enhancing two-way trade and investment to respectively USD 1 thousand billion and USD 150 billion by 2020 [12].

Despite speaking highly of initiatives and posture in signing ACFTA of China, ASEAN countries still take extra precautions in two following points. Firstly, ACFTA seems to benefit China more than ASEAN countries. Due to the higher competitiveness, Chinese enterprises penetrate into ASEAN market more efficiently in comparison to ASEAN enterprises infiltrating into Chinese market. This trend leads to the trade deficit in goods for all ASEAN members but Singapore, thereby creating an aversion to China’s goods and the hostility between local enterprises and the governments in many ASEAN countries. Secondly, small countries worry that the overdependence in terms of economic affairs on China will weaken their rights and abilities to negotiate in security issues. ASEAN countries can thus lose the self-determination in their external policies with China in the future. This was proved in the past when China used Phnom Penh to stop the statement of ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting on the protest against China with regard to issues in the China Sea [17]. In addition, the protest of the Philippines against China’s declarations in the South China Sea tends to decline under the administration of President in comparison to the administration of President Aquino because Duterte thinks that the economic support from China is more important than its sovereignty claim in the South China Sea.

Therefore, while ACFTA and related infrastructure initiatives are crucial mechanisms for enhancing trade and investment between ASEAN and China, the strategic partnership between the two sides has not yet been finalised and strongly developed. From the late 1990s onwards, China has tried to strengthen economic relations with ASEAN, but the increasing trade deficit and inadequate mutual confidence are hindrances to ASEAN - China relationship. The mutual confidence of China and ASEAN in security issues seems to fail to match the trade value of both sides [5]. This is considered the decisive point that China should make a necessary change in the future. To mark the milestone of 15 years of strategic cooperation, Beijing has proposed to elevate the current “2+7” cooperation framework to “3+X” one, through which China tended to create a new cooperation framework based on three pillars, namely political security, economic affairs and people exchange, to match the objectives of ASEAN Community. Because the number of agendas for cooperation has not been determined yet, China needs to pay more attention to concerns of ASEAN so that the “3+X” cooperation framework can take effect and be more valuable.

According to China’s statement in the past on the improvement of trade balance between the two sides, it needed to have specific action plans. China - ASEAN exhibition6, starting in 2004, was a useful forum for producers and manufacturers in ASEAN to introduce their goods and products in the Chinese market. However, this forum is not enough to narrow down the trade deficits that ASEAN countries have to face in their trade relations with China. In addition, the service area needs to be strengthened. Meanwhile China is a considerable importer of services in transport, tourism and others, Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia are leading exporters of these services. This creates a huge trade potential among these countries in the service area, thereby promoting ASEAN - China trade and service relations.

In the current context, ASEAN and China need to expand the scope of cooperation to new fields, including e-commerce. With the 4th industrial revolution, the two sides should promote cooperation in areas such as technology innovation and digital economics. When ASEAN started the cooperation mechanism within the region in developing a network of smart cities in 2018, China played a big role in sharing experience because it had more than 500 underway smart city projects [19].

Finally, although the joint efforts and cooperation between ASEAN and China can be created between MPAC of ASEAN and BRI of China, these projects need to be developed in the way that both sides can benefit from them. China should not consider investments in MPAC as a way for this country to have strategic assets from ASEAN countries by creating influence and dependence, through which China can raise its military influence or access to natural resources. Instead, investments in projects within the framework of MPAC from China must be a prerequisite to enhance the manufacturing and technology transfer and generate jobs for ASEAN countries. Most importantly, through such investments, China should set the objective of promoting integration within the framework of ASEAN countries in a stronger manner instead of manipulating geopolitical issues in the future of the South East Asia and making it the backyard of China. In that situation, economic relations between the two sides do not have any role in promoting ASEAN - China strategic partnership.

4. Conclusion

Economic cooperation is an important aspect and factor in ASEAN - China strategic partnership. Over the past many years, the trade and investment between the two sides have made contributions to strengthen ASEAN - China economic relations. However, there remain concerns within ASEAN countries about the trade deficit, leading to the enormous economic and political dependence on China, which can cause ASEAN countries to lose their negotiation abilities in political affairs and external policies.

Currently, when China wants to elevate the existing China - ASEAN relationship through the vision of ASEAN - China strategic partnership, this country needs to mind and pay more attention to concerns that ASEAN countries are facing to find concrete solutions to create the mutual confidence, the crucial foundation for developing a strong strategic partnership between ASEAN and China. After all, economic link must bring about benefits for all countries and people before it can make active contributions to a form of institutionalising the vision to 2030 of ASEAN - China cooperation and strengthen ASEAN - China strategic partnership. Only if ASEAN believes in China and can phase out the fear of trade deficit and the economic reliance on China, will ASEAN be confident to elevate the strategic partnership with China to a new level of comprehensive strategic partnership in the future.

____________________________

Notes

1 The paper was published in Vietnamese in: Nghiên cứu Đông Nam Á, số 7, 2018. Translated by Vu Xuan Nuoc.

2 Specifically, two shared perceptions are to continue developing the confidence and good neighbourhood between the two sides, including issues in the South China Sea and to focus on promoting the win-win economic cooperation. Seven petitions are to actively discuss the possibility of signing a good neighbourhood agreement, start the negotiation on elevating ACFTA, speed up the regional infrastructure connectivity, promote the regional financial cooperation to prevent risks, prompt the sea cooperation, strengthen the cooperation in security areas and enhance the cooperation in science and technology and human exchange.

3 Calculations based on statistics, which are collected from the trade date system of the WTO.

4 In 2010, ASEAN countries importing Chinese goods bore an average import tax rate of 0.6% (in comparison to the previous rate of 12.8%); meanwhile, China was only taxed 0.1% (in comparison to the previous rate of 9.8%) in importing goods from ASEAN countries.

5 Other cooperation programmes include signing a good neighbourhood agreement, starting the negotiation on elevating ACFTA, speeding up the regional infrastructure connectivity, promoting the regional financial cooperation to prevent risks, prompting the sea cooperation, strengthening the cooperation in security areas and enhancing the cooperation in science and technology and human exchange [14].

6 The China-ASEAN EXPO (CAEXPO) exhibited goods and products from ASEAN countries and China. This event has been organised and hosted by China once a year since 2004. Sideline events of CAEXPO comprising ASEAN – China Investment and Business Summit were held to gather the government and private sector to discuss viewpoints on issues of common interest of the two sides.

References

[1] ASEAN Secretariat and UNCTAD (2015), ASEAN Investment Report 2015: Infrastructure Investment and Connectivity, Jakarta, Indonesia.

[2] ASEAN Secretariat (2017), Joint Statement between ASEAN and China on Further Deepening the Cooperation on Infrastructure Connectivity, Manila, Philippines.

[3] ASEAN Secretariat (2003), Joint Media Statement of the 2nd ASEAN-China Transport Ministers Meeting, Yangon, Myanmar.

[4] ASEAN Secretariat (2016), Joint Statement of the 19th Asean - China Summit To Commemorate the 25th Anniversary Of Asean-China Dialogue Relations, Jakarta, Indonesia.

[5] Anuson Chinvanno (2015), "ASEAN-China Relations: Prospects and Challenges", Rangsit Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (RJSH), Vol. 2, No. 1, pp.9-14.

[6] Ishido, Hikari (2011), "Liberalization of Trade in Services under ASEAN+n: A Mapping Exercise", ERIA Discussion Paper, No. 2.

[7] Koon Peng Ooi (2016), Examining the Impact of ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement on Indonesian Manufacturing Employment, CSAE Working Paper (WPS/2016-15), University of Oxford.

[8] Stephen V. Marks (2015), "ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement: Political Economy in Indonesia", Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, Vol 51 (2), pp.287-306.

[9] Yang, Chunmei (2009), "Analysis on the Service Trade between China and ASEAN", International Journal of Economic and Finance, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp.221-24.

[10] Yuzhu, Wang and Sarah Y. Tong. (2010), "China–ASEAN FTA Changes ASEAN’s Perspective on China", East Asian Policy, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp.47-54.

[11] http://asean.org/?static_post=external-relations-china-joint-declaration-of-the-heads-of-stategovernment-of-the-association-of-southeast-asian-nations-and-the-people-s-republic-of-china-on-strategic-partnership-for-peace-and-prosp, retrieved on 1 May 2018.

[12] http://www.asean.org/storage/images/archive/2 3rdASEANSummit/7.%20joint%20statement% 20of%20the%2016th%20asean-china%20summit %20final.pdf, retrieved on 20 May 2018.

[13] https://www.aseanstats.org/publication/tour ism-dashboard/, retrieved on 4 June 2018.

[14] http://www.asean-china-center.org/english/ 2013-10/10/c_132785560.htm, retrieved on 10 May 2018.

[15] http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2017-11/ 13/content_34491398.htm, retrieved on 25 April 2018.

[16] https://thediplomat.com/2018/02/what-does-chinese-investment-mean-for-cambodia/, retrieved on 8 May 2018.

[17] https://thediplomat.com/2012/07/asean-summit-fallout-continues-on/, retrieved on 6 April 2018.

[18] https://globalriskinsights.com/2018/01/money-talks-chinas-belt-road-initiative-cambodia/, retrieved on 16 May 2018.

[19] http://www.pmo.gov.sg/newsroom/people%E2 %80%99s-daily-interview-pm-lee-hsien-loong, retrieved on 24 April 2018.

[20] http://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-election-china/in-indonesia-labor-friction-and-politics-fan-anti-chinese-sentiment-idUSKBN 17K0YG, retrieved on 22 April 2018.

[21] http://www.scmp.com/week-asia/society/article/ 2102934/thailand-chases-chinese-money-what-cost, retrieved on 6 May 2018.

[22] http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-01/28/ c_136931519.htm, retrieved on 6 July 2018.

[23] http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-09/14/ c_136610183.htm, retrieved on 7 June 2018. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/ pub_2354_ann2.pdf, retrieved on 23 May 2018.

Sources cited: JOURNAL OF VIETNAM academy OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, No. 4 (192) - 2019